Protecting American interests

The U.S. government understands what your science teacher insisted during sophomore year: Chemistry does indeed have real-world applications.

Defense missions, strategies, tactics and tools continue on a trajectory of rapid technological evolution and cutting-edge innovation. Significant defense applications for REEs today include electronic displays, guidance systems, lasers, and radar and sonar systems. The government understands REEs will continue to be critical technological components of warfare and national security, and it is acting accordingly.

The Trump administration issued an executive order in December 2017, outlining a strategy to “ensure secure and reliable supplies of critical minerals.”

Fast forward to Feb. 1, 2021, when the Department of Defense awarded a Defense Production Act Title III technology investment agreement to Lynas Rare Earths Ltd., the largest rare-earth element mining and processing company outside of China. The public company is registered on the Australian Securities Exchange.

As part of this agreement, the Pentagon will contribute $30.4 million toward the development of a new facility in Hondo, Texas, supplementing Lynas’ operations in Australia and Malaysia. The stated goal of this agreement is for Lynas to produce approximately 25% of the world’s supply of REE oxides.

About three weeks after the DOD announced the Lynas agreement, President Biden issued an executive order requiring federal agencies to perform a detailed review of their supply chains in light of the government’s heightened concerns relating to Chinese suppliers and supply chain risk. A key recommendation from these supply chain reviews, published in June 2021, was for the government to “create 21st century standards for the extraction and processing of critical minerals at home and abroad,” with a specific callout to REEs.

The United States’ determination to stifle China’s influence on government supply chains is further illustrated in the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for fiscal year 2022, as drafted in July by the Senate Armed Services Committee. For example, the act would prohibit the Secretary of Defense from procuring personal protective equipment manufactured in China, as well as Russia, North Korea and Iran.

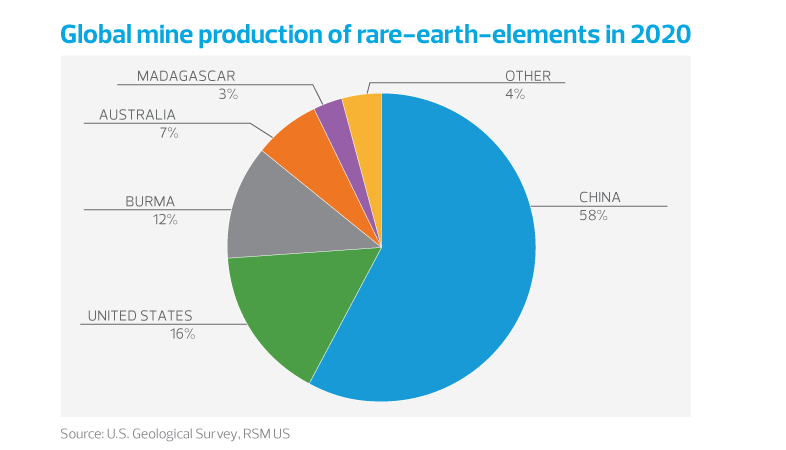

The United States and other countries are stepping up investment in rare-earth element mining and production activities to lessen China’s stronghold on them and provide some much-needed supply chain freedom and flexibility.

The leverage and pricing power China garnered by sourcing 80% of the rare-earth compounds and metals that the United States imported from 2016 to 2019 does not sit well with the U.S. government, especially after a year ridden with national security concerns and supply chain issues exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Now that the American response is underway, government contractors—particularly those in the defense technology realm—face a changing ecosystem.

Potential regulation and the path forward

Government contractors that participate in the defense technology arena should be keenly aware of the role REEs play in their industry, as well as the extent to which they touch company operations and supply chains.

Based on history and recent government actions relating to sourcing materials from certain countries (including China), our view is that rare-earth minerals will likely be regulated, similar to:

- Section 889 of the NDAA for FY 2019, requiring telecommunication equipment and services from certain Chinese vendors to be identified and removed from operations and supply chains

- The Buy American Act, requiring that steel and iron be sourced domestically

- The Dodd-Frank Act conflict minerals rule, requiring disclosure of conflict minerals (tantalum, tin, gold or tungsten) to ensure U.S. production is not contributing to a humanitarian crisis in the Democratic Republic of Congo

Those examples amount to a precedent for the federal government to require certification that rare-earth minerals from certain locations or providers are not present in the supply chain, not only at the end-product level but also at the component and even subcomponent level.

There is potential for exceptions under the Buy American Act, such as commercial IT products or limited quantities found in goods produced domestically. Further, there is the possibility that sourcing from countries included in the list of the Trade Agreements Act, such as Australia, will be encouraged.

While uncertainty remains, the U.S. government has a record of imposing regulations to stimulate domestic production and limit economic dependency on China. We recommend clients identify products that incorporate REEs, assess the impact of changing Chinese-sourced REEs to supply chain partners in the U.S. or countries under the Trade Agreements Act, and develop a contingency plan.

A prepared supply chain is a resilient supply chain.