Concerns around rising prices are directly linked to the fiscal spending in 2020 that was equal to approximately 20% of gross domestic product and put in place to offset the loss of income during the pandemic. The prospect of another $2 trillion this year and roughly $1.65 trillion in excess household savings has only fueled concerns over the pent-up demand and over-the-top spending by consumers once the pandemic has been contained.

Given that more than 75% of the new relief package is one-time disaster aid and is not a permanent increase in spending, the talk of runaway inflation is not only erroneous, but it also ignores the dynamic structural changes in the economy over the past two decades.

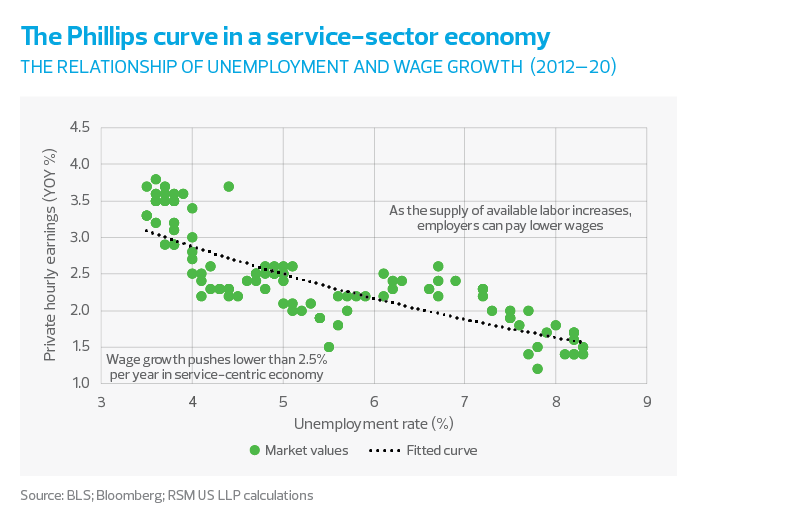

The major difference in distinguishing between transitory and permanent price increases is growth in wage income. Although the employment cost index is showing a solid 2.5% increase year over year, this recovery is K-shaped, meaning that wage gains among higher-income earners are outstripping lower-income workers. This distorts the true underlying downward pressure on wages. For inflation, it means that a persistent and permanent increase through the wage channel is a non-starter, and that inflation is most likely years away.

Policymakers and the public should not anticipate sustained upward pressure on the economy while the labor market remains 10 million jobs short of its pre-pandemic levels, real unemployment hovers near 10% and several million people have taken a pay cut to remain on the job.

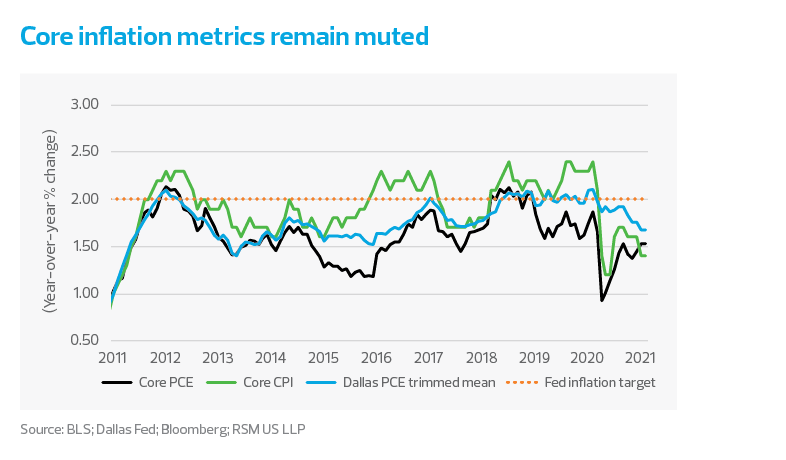

Current conditions indicate that tepid wage growth and plentiful slack in the labor market are simply not conducive to a persistent increase in inflation. This is why the Federal Reserve has made abundantly clear that it is not interested in raising interest rates until labor conditions return to pre-pandemic levels or what we interpret to be full employment at or below a 3.5% unemployment rate.

Policy implications

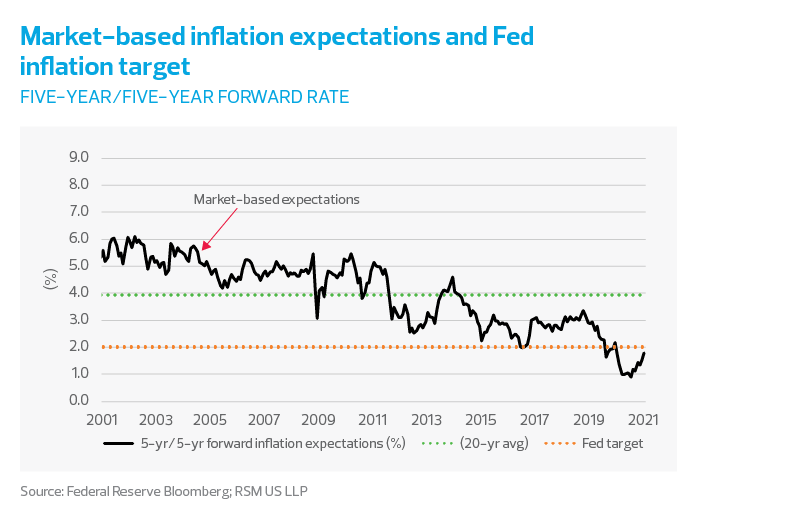

The market has priced in a rate hike in the first quarter of 2023, which we think is out of line with the fundamentals. Nevertheless, the backup in interest rates in general and the increase in the five- and 10-year Treasury yields will have gained the Fed’s attention. At this point, the Fed will most likely look to make subtle policy changes that do not alter the size of its balance sheet but extend the duration of its portfolio.

At the front end of the yield curve, we expect that the Fed would, if need be, lift interest rates paid on excess reserves (currently 10 basis points) and overnight repo rates (currently zero) by 5 basis points each.

As to longer maturities, it would not be surprising if central banks began hinting at a possible Operation Twist III—or the simultaneous buying of long-term bonds and selling of short-term bonds. The intent would be to dampen rates at the long end of the yield curve, while extending the duration of its portfolio without increasing the size of the Fed’s balance sheet. The Fed has used this approach twice before—in February 1961 and in September 2011.

This would signal to other policymakers, market players and investors that the central bank intends to achieve its policy goals and is willing to inflict losses on those who challenge its credibility.

The economic data does not scream inflation, stagflation or dollar debasement. Rather, it implies long-run price stability.

Quality improvement and the digital economy: Bring the noise

Within the community of policymakers and economists, it is generally understood that technological innovations, productivity gains and the rise of the digital economy have mitigated increases in inflation. But many in the financial sector are operating on old heuristics, or rules of thumb, that are no longer adequate to ascertain risks around pricing and the direction of inflation.

For example, quality adjustments over the past decade have resulted in a noticeable impact on the cost of durable goods inside the PCE index. Over the past 25 years, the cost of durables has fallen by 38%. If one includes quality improvement in the auto goods and parts sector, prices have increased by only 9% since 1995.

While those improvements in quality are widely accepted as a tempering factor on inflation, the rise of the digital economy and its impact on the cost of services are not. In fact, we would make the case that the digitization of the service sector is profoundly disinflationary. As Erik Brynjolfsson writes in his book, Machine, Platform, Crowd, once something is digitized, the cost of reproduction, distribution and access tends to fall toward zero. This is not your father’s or grandfather’s economy.

With the rise of zero-pricing business models in everything from entertainment, banking and financial trading, this shift is one of the structural changes not included in many of the arguments and explanations on why inflation might be a rising risk.

From our vantage point, those making the case about the return of 1970s-style inflation are prisoners of the past and fighting the wars of the 1960s and 1970s. They are missing the broad structural changes reshaping the economy.

MIDDLE MARKET INSIGHT

Policymakers and the public should not anticipate sustained upward pressure on the economy while the labor market remains 10 million jobs short of its pre-pandemic levels, real unemployment hovers near 10% and several million people have taken a pay cut to remain on the job.

Pricing expectations and the real economy

The recovery of oil, energy and commodity prices has facilitated an increase the cost of goods used at earlier stages of production and some intermediate goods. Given historical declines in economic activity during the first half of 2020 and those prices—the cost of West Texas Intermediate closed at negative $-37.63 a barrel on April 20, 2020—a reflation in prices and expectations around inflation was always going to be part of the narrative once economic reflation began.