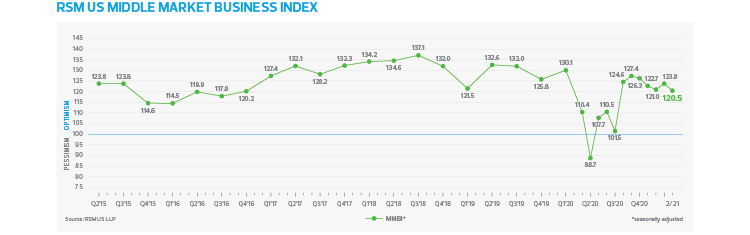

Middle market business sentiment remained solid in February as the economy absorbed a nasty winter storm and what is hoped to be the final blow from the pandemic, according to RSM’s proprietary survey of middle market executives. The RSM US Middle Market Business Index declined modestly in February to 120.5 from 123.8 the month before.

In our estimation, the release of pent-up demand and a renaissance of capital spending expected to begin in late spring will bolster both the top-line index number and current observations underscoring the forward-looking sub-indices that support the index.

To a certain extent, the executives’ views on the economy, earnings, revenues, hiring and compensation all reflect the bifurcated nature of sentiment late in the public health crisis—they expressed a dour current view of the market but at the same time had a much more optimistic and robust view of what is to come.

Because these views have not materially changed over the past month, we want to explore the current conversation of the moment: the middle market’s focus on rising prices as the economy reflates amid still-constrained supply chains.

The ability of our respondents to pass along price increases will, on the margin, determine whether the recent increase in prices paid for goods used in earlier stages of production as well as intermediate goods will result in a temporary increase in prices for end users. That’s the official forecast of the Federal Reserve and is a view that we agree with. The other possibility is if these higher costs are successfully passed along and result in sizable increases in rising wages and a permanent increase in the price level across the economy.

In February, 58% of executives surveyed noted that they faced higher prices paid for goods, which was down from 66% in January. Only 17% of the executives reported a decline in prices. But on the question of forward-looking prices paid, 69% said they expect to pay higher prices, 10% lower prices and the remainder expect no change.

How many middle market firms indicate an ability to pass along price increases currently and over the next six months? Given the recent move up in real and nominal yields, the answer might be surprising.

Only 38% of respondents said that they received higher prices for goods or services, 23% said those prices had decreased and 39% noted there was no change. As for the forward look on prices received—the ability to pass along prices paid—59% indicated that they intend to try to pass along price increases, 9% said they expect to cut prices (likely absorbed via thinner margins) and 31% said they expect not to pass along those increases.

So what business-sensitive information can we ascertain from this data?

First, firms that have long not been able to pass along price increases are somewhat skeptical of being able to do so. While a majority intend to try, this may prove quite difficult because of the reopening of the global economy and what we expect to be a hypercompetitive post-pandemic economy defined by the pulling forward of a decade or more of technological investment into the next two to three years.

Second, middle market firms will need to focus immediately on increasing efficiencies and engage in productivity-enhancing investment to address rising input prices because of supply chain constraints that may take 12 to 18 months to smooth out, as they wait for prices to return to pre-pandemic equilibria.

Current readings on capital expenditures indicate that only 29% of executives increased investment on software, equipment and intellectual property in February, and 47% intend to do so over the next six months. That is one area of the real economy where there will need to be a noticeable improvement as the economy reopens.

Third, this data does not point to an immediate and permanent increase in the price level across the economy. Rather, it points to a temporary disruption in supply chains, and a transitory increase in inflation caused by year-ago base effects, or the simple arithmetic of rising prices after their near collapse during the first few months of the pandemic.

Fourth, the recent backup of Treasury yields along the long end of the maturity spectrum looks to be overdone. We would not be surprised if the Fed begins to use its potent policy toolbox to begin dampening rates along the long end of the curve. That could occur through so-called “open-mouth operations” in which the Fed jawbones rates lower. Or it could be through the selling of Treasury bonds in the Fed’s portfolio at the front end of the curve, then taking the proceeds and purchasing bonds at the long end. This maneuver would address moves in market-derived Treasury rates that are out of line with economic fundamentals. We do not expect the recent increase in rates to be sustained in the near term.

Finally, the U.S. economy and the middle market are comprised of firms that provide services. That means inflation is primarily a function of wage pressures. Currently, only 32% of firms reported an increase in compensation, 21% noted a cut and 45% stated that wages and salaries remained unchanged. While 56% noted they would increase compensation over the next six months, this data is simply not consistent with a permanent increase in inflation through the wage channel that would alter both the Fed’s and RSM’s inflationary outlook.