The Fed’s inflation target will need to be 3%, not 2%, to avoid the loss of millions of jobs.

Key takeaways

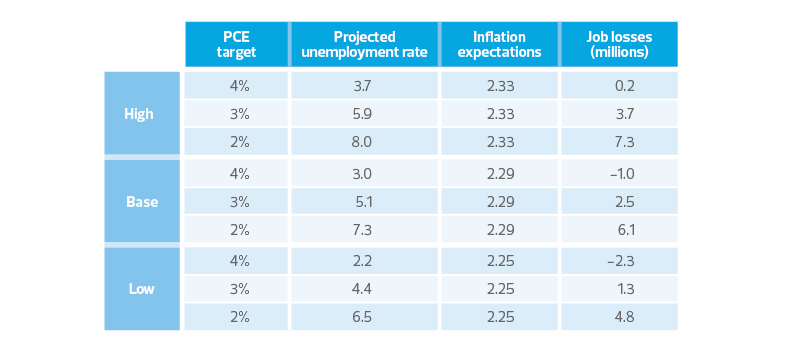

Our research shows that level would mean the loss of 2.5 million jobs.

But the figure could reach as high as 7.3 million jobs, depending on how far the Fed goes.

Events have outpaced the best-laid plans of policymakers. The recent turmoil in the financial sector will place constraints on the Federal Reserve’s efforts to restore price stability.

Our research indicates that the Fed, facing persistent inflation, will for now have to accept a de facto inflation target of 3% to avoid the destruction of millions of jobs that would accompany achieving a 2% target.

This means a difference of somewhere between 1.3 million and 7.3 million jobs lost, depending on how aggressively the Fed ends up fighting inflation, according to our research.

Under our base case, a loss of 2.5 million jobs is consistent with a 5.1% unemployment rate, 3% inflation and a likely recession under current economic conditions.

To achieve this, though, the Federal Reserve faces a difficult proposition: how to achieve price stability while maintaining financial stability during a modest financial panic and bank crisis.

Both the European Central Bank and the Federal Reserve have provided prodigious injections of liquidity recently to stem bank runs and financial panics. If anything, those efforts are in their initial stages and more will most likely be needed as financial institutions absorb interest rate hikes.

And the central banks still face elevated inflation. The European Central Bank recently hiked its policy rate by 50 basis points to 3.5%, despite a rescue of Credit Suisse and a warning by the ECB to the European Union that other euro-area banks may be at risk.

The Federal Reserve followed that with a quarter-point rate hike at its March meeting.

With both inflation and unemployment rates remaining sticky, we believe it is important to update our estimates ahead of the next set of forecasts released by the Federal Reserve.

While the Fed hiked its policy rate by 25 basis points to a range of 4.75% to 5%, it is important to revisit the price stability side of the equation and update our estimate of the sacrifice ratio, or the slope of our augmented Phillips curve, to identify the trade-off between inflation and unemployment.

The sacrifice ratio

Seven months after we published our first estimate of how much the unemployment rate would have to increase to bring inflation down to the long-term target, the fight against inflation remains far from finished.

The Federal Reserve indirectly validated our initial results in its December Summary of Economic Projections; the unemployment rate would have to rise to 4.6% to bring inflation down to 3% by the end of this year.

Now, we have revisited our estimate of the sacrifice ratio given the changes in the economy.

The results are not encouraging. Our new results suggest that the economy would have to sacrifice more to reach the same goal.

To reduce inflation to acceptable levels—using the personal consumption expenditures price index, the Fed's key inflation metric—would mean the loss of 2.5 million to 6 million jobs, an increase of approximately 700,000 above our initial estimates.

The unemployment rate, as a result, would have to rise to between 5.1% and 7.3%.

Inflation expectation risks

One reason for our upward revision is that inflation in core services has remained stubbornly high. Another is that inflation expectations have drifted higher, which implies a higher cost to return inflation back toward the long-run 2% target.

Central bankers tend to be transparent when it comes to hiking rates and the need to maintain well-anchored inflation expectations. The goal is to ensure the public understands that the central bank intends to achieve price stability and will use the policy tools at its disposal to reach that objective.

For some time, the use of forward guidance through transparent public communication has played a significant role in monetary policy. And the Fed has relied on that part of its toolbox since inflation soared in 2021.

But elevated and persistent inflation caused inflation expectations to move above our forecast of 2.15%, according to the Fed's Index of Common Inflation Expectations. That index from the Fed remained at 2.33% in the last quarter of 2022. An alternative market-based metric—the Fed’s five-year forward breakeven—currently stands at 2.255%.

This mild increase demands further policy action from the Federal Reserve at the risk of more financial volatility that may cause financial conditions to tighten further.

While a few basis points between the actual rate and the forecasts may seem small, they are critical, according to our model. The modest increase in inflation expectations turns out to be the most meaningful element in our model and is critical to understanding the cost of restoring price stability amid financial turmoil.

Three scenarios

To illustrate our model, we use three scenarios using three different levels of inflation expectations following the same method outlined in our first study.

We make one key adjustment to the model in this simulation.

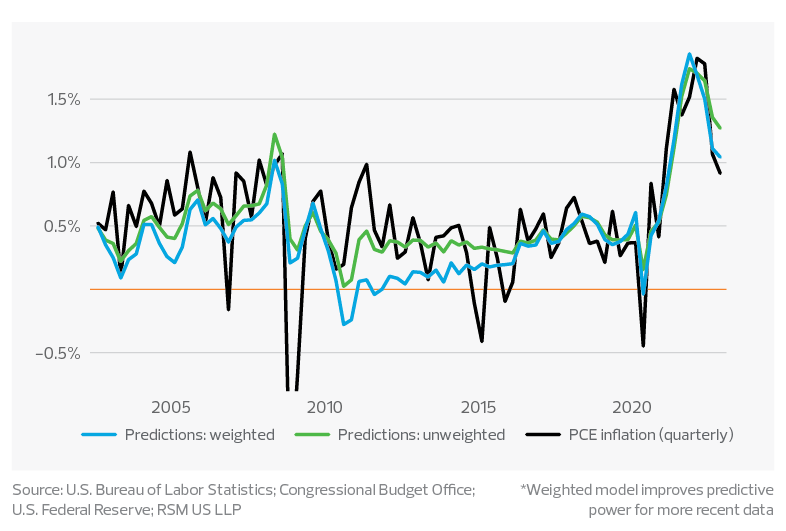

Considering the significant shift in economic conditions, especially since the beginning of the pandemic, we introduce weights to each data point such that the more recent a data point is, the greater the weight it receives.

The new approach improves the predictability of the model by almost 100%, especially for the more recent data points as shown in the figure below.

Phillips curve predictions vs. actual inflation*

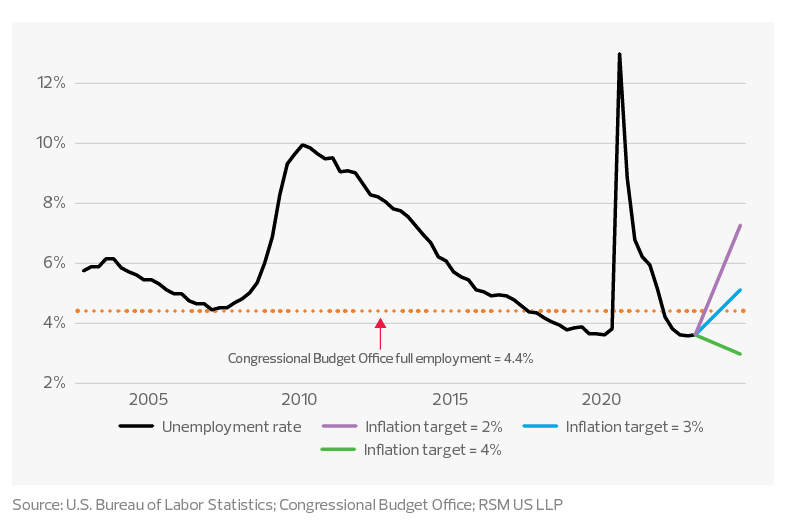

In the first scenario, where inflation expectations remain at 2.29%, the economy would have to shed 2.5 million jobs and the unemployment rate would reach 5.1% for inflation to reach our base case of a 3% (PCE deflator) rate.

In our estimation, this is a reasonable and achievable policy outcome given prevailing economic and financial positions. Reaching a more ambitious 2% inflation target, though, would result in the loss of 6.1 million jobs and result in an unemployment rate of 7.3%.

In the second scenario, in which inflation expectations remain at 2.33%, where they stood at the end of last year, the economy would need to shed 3.7 million jobs and the unemployment rate would need to increase to 5.9% to reach an inflation rate of 3%.

A 2% inflation target under that scenario would result in an unemployment rate of 8% and a loss of 7.3 million jobs.

In the third scenario, where inflation expectations drop to 2.25%, 1.3 million jobs would be lost and the unemployment rate would rise to 4.4%, which is the Congressional Budget Office estimate of full employment. This scenario, the most optimistic of the three, could happen as capital flows from smaller institutions to larger institutions and lending tightens, reducing expectations of inflation.

Magic number 3

Before the recent banking turmoil, the Fed had communicated its intention to choose taming inflation over keeping the unemployment rate low, which signaled a willingness to sacrifice millions of jobs.

But the choice now seems less obvious as financial stability enters the equation.

The most difficult aspect of our modeling is that to bring down inflation to a tolerable level between 2% and 3%, the Fed will have to induce a recession.

How much unemployment must rise to reach inflation target

That outlook has been our base case for this year and accounts for our estimate of a 65% probability of a recession starting in the second half of the year.

Given what is likely to be a tightening in lending over the next few months, that recession is more likely to occur amid a rising cost of capital, reduced lending and job losses associated with both.

This argues for a near-term policy peak in line with our current forecast of 5.25% to 5.5%, with the risk of a lower peak because of financial instability.

But the magnitude of the downturn that the Fed intends to induce partially depends on the Fed’s official target versus what it is willing to accept.

The takeaway

In our estimation, the policy steps necessary to bring inflation down to 2% would result in a deeper recession than necessary. Few should be surprised if the Fed accepts 3%, at least in the short run. Once it is confident that inflation will ease to 3%, then it can consider a true pivot to accommodation if financial volatility refuses to subside.

In the bigger picture, we have argued that inflation is likely to be higher for longer, requiring higher rates, because of structural changes in the economy. These changes include the selective decoupling of the American economy from China and changing demographics that limit the American labor supply.

That should give the Fed more than ample rationale to tolerate inflation running at 3%, especially given that in the decade before the pandemic, inflation averaged roughly 1.5%.