Debt ceiling crisis: how will it cost middle market businesses?

We are in the early stages of yet another round of policy brinkmanship over the nation’s finances.

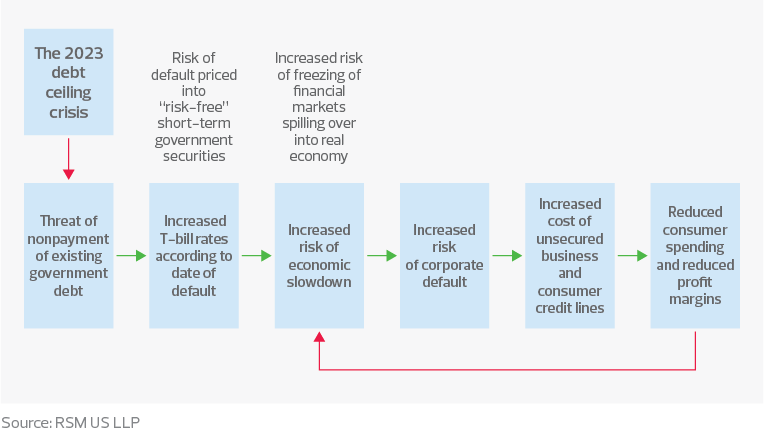

The risks to the middle market and the broader economy posed by a potential failure to raise the debt limit are bound to disrupt everything from local business financing to international trade, with the potential for long-term damage to growth.

The nation’s debt reached its statutory limit on Jan. 19, causing the Treasury to begin taking extraordinary measures to avoid breaching that limit while continuing payments on existing debt. On Jan. 23, for example, the Treasury began deferring payments to government pension plans. But the costs of this political gambit are starting to show. Money markets have already exhibited signs of distress, with investors shying away from the six-month Treasury bill auction in anticipation of a June drop-dead date for government default.

This could translate into increased costs for lines of credit necessary for businesses to conduct day-to-day operations and an unwillingness to undertake expansion if businesses think it prudent to wait out the crisis. In the longer run, there is the risk that a constant stream of manufactured crises will have more permanent consequences for U.S. financial markets, the dollar and the economy.

Already a series of cascading shocks have threatened global financial stability and economic growth, according to the International Monetary Fund. That the economy has overcome these shocks is a testament to the strength of the global financial system.

But none of this can be taken for granted. Western economies have been able to grow only because of the soundness of the U.S. Treasury market and the dollar, operating within the rules and regulations of Western economies.

The mere threat of an outright default on the debt would send investors the world over into the safety of cash holdings. This isn’t conjecture; investors sold off their holdings and moved into cash three years ago, during the height of the pandemic. That flight to safety also happened in the wake of the financial crisis.

A default on U.S. debt would prompt a similar move to cash and cause a significant shock to the global financial system, triggering large swings in stock prices, private interest rates and the value of the dollar.

Take, for instance, the diminished transaction demand for dollars, in which proceeds from trade for goods and commodities are parked in Treasury securities. The decreased demand for those securities would pressure domestic interest rates higher, increasing the cost of credit and reducing domestic demand.

It took a decade to recover from the financial crisis, and that was set off by excessive leverage in the financial system. Another crisis, this one set off by a default on government debt, would reduce the long-term incentive to invest and further weaken the economy’s potential growth.

For businesses, declines in consumer confidence and discretionary household spending would lead to a drop in revenue. That would result in the government’s self-inflicted wound of reduced tax revenues and increased debt.

In the analysis that follows, we show that even brinkmanship would have a detrimental effect on economic growth, employment and price stability. A default on our debt would be devastating.

Q: Who pays the cost of a debt ceiling crisis?

A: The business community and consumers.

Another debt ceiling crisis is approaching, and it is in no one’s best interest.

Policy brinkmanship over lifting the debt ceiling and the threat of default are increasing the cost of doing business and carry far more risk than is commonly acknowledged.

At its core, the standoff is an artificial crisis induced by the political authority and will be difficult to contain if it is allowed to spiral out of control.

But what happens if a default takes place? To better understand the risks—and they are substantial—we modeled out scenarios to estimate the probable outcomes on employment, growth and inflation.

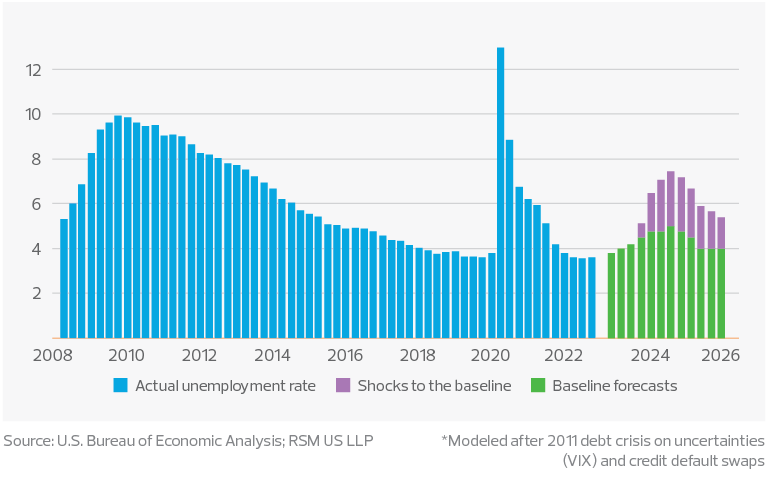

A technical default

The first scenario is a technical default, which is defined as an extended period of nonpayment of some or all U.S. financial responsibilities. Based on our shock model, a technical default would double the current unemployment rate of 3.4% to near 7%, tip the economy into recession within six months and, following a short bout of disinflation, result in a more persistent bout of inflation accompanied by a deterioration in the fiscal condition of the economy.

A technical default's impact on unemployment rate*

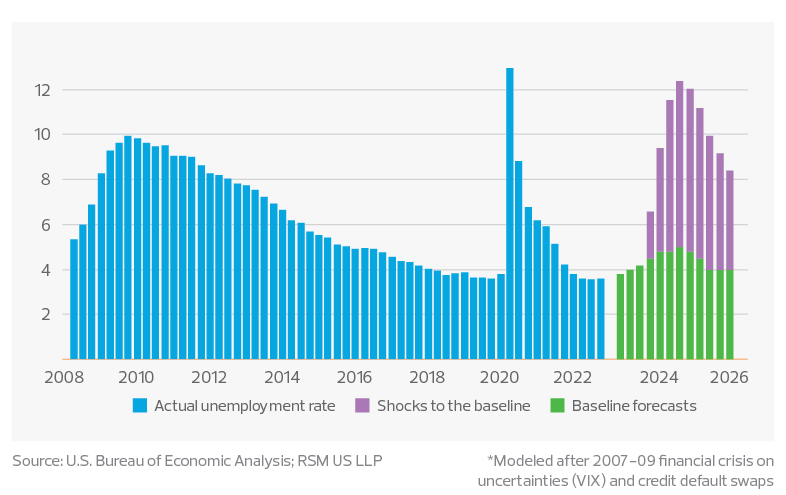

An actual default

The second scenario would be an actual default, in which the government, out of money, stops paying its obligations. It would be an unfettered economic catastrophe. Our model indicates that unemployment would surge above 12% in the first six months; the economy would contract by more than 10%, triggering a deep and lasting recession; and inflation would soar toward 11% over the next year.

Under both scenarios, the U.S. credit rating would be downgraded, the dollar would be put in jeopardy, and the cost of floating debt by both the American private sector and government would rise.

In addition, the small and medium-size enterprises that constitute the backbone of the American economy, unable to absorb such a shock, would suffer irreparable harm.

An actual default's impact on unemployment rate*

Based on the experience of the 2011 and 2019 debt ceiling standoffs, our base case is that the political authority will tempt fate, courting default and putting domestic and international economic stability at risk, before striking a deal.

But the deal would not accomplish much in the way of addressing the government’s long-term spending imbalance. The primary budget deficit—the deficit minus interest owed on past debt, which in our estimation is the correct metric to focus on to achieve fiscal stability—stands at 3.27% of gross domestic product.

Putting the primary budget deficit on a path to a more sustainable rate of 2% over the next decade is something that the political authority could accomplish outside an unnecessary and artificially induced crisis.

Lessons learned

To better understand the risks, we simulated what a debt ceiling crisis would look like using two scenarios: the 2011 debt ceiling crisis and the 2007-09 financial crisis.

The 2011 debt ceiling crisis pushed down asset prices, reduced household spending and private business investment, and eroded consumer and corporate confidence. Even though the 2011 debt crisis was more benign than the financial crisis, a modest technical default along those lines that drags on for a few weeks would still damage the U.S. economy.

The financial crisis, by contrast, serves as a better comparison if there is a full-scale default. The impact of such a default would be transmitted through the economy through the financial markets and would affect the real economy following a short lag. The results would be catastrophic.

Debt ceiling shock model

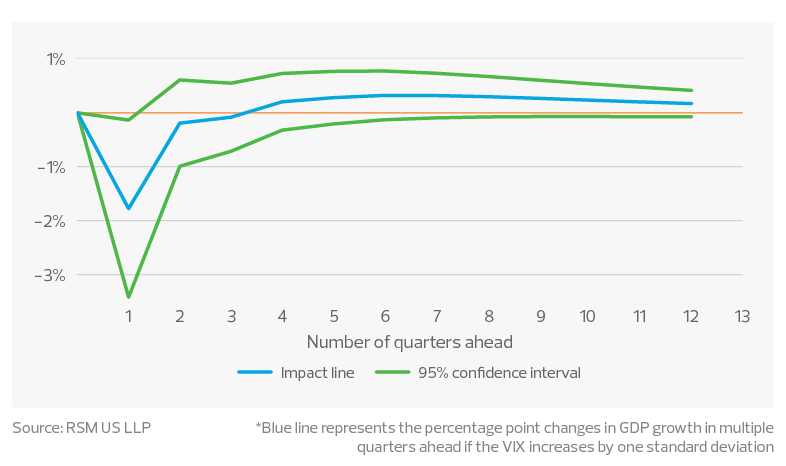

We used the Chicago Board Options Exchange volatility index, or the VIX, as a proxy for financial and economic risk and uncertainties and the one-year credit default swap rate as a proxy for credit risks.

Both serve as leading indicators in determining the full impact on growth, inflation and unemployment. A vector autoregression model captures the relationship among multiple factors over a period of time.

Our choice of proxies was motivated by the anticipation that the financial markets would be the initial channel through which the economy would be subject to stress.

Our findings indicate that the selected proxies have strong correlations, with a 95% confidence level.

For instance, an increase of one standard deviation in the VIX would result in a decline of approximately 1.7 percentage points in gross domestic product on an annualized basis during the subsequent quarter. This decline would persist over the following two quarters before turning positive.

Impact of a one-time VIX shock on GDP growth*

It will be some time—we think between July and September—before the U.S. government reaches a date that risks default. It is reasonable to assess the economic impacts from the last quarter of 2023 to the end of 2025.

At the depth of the financial crisis, market uncertainties stayed extremely elevated for nearly nine months—with the VIX at an average of three standard deviations above neutral. On top of that, the one-year rates on credit default swaps rose more than 40 basis points in six months.

If the same market movements took place this time because of a government credit default, the consequences would most likely be worse. This underscores our analysis that the current crisis is already subjecting the economy to financial stress that is increasing the cost of doing business.

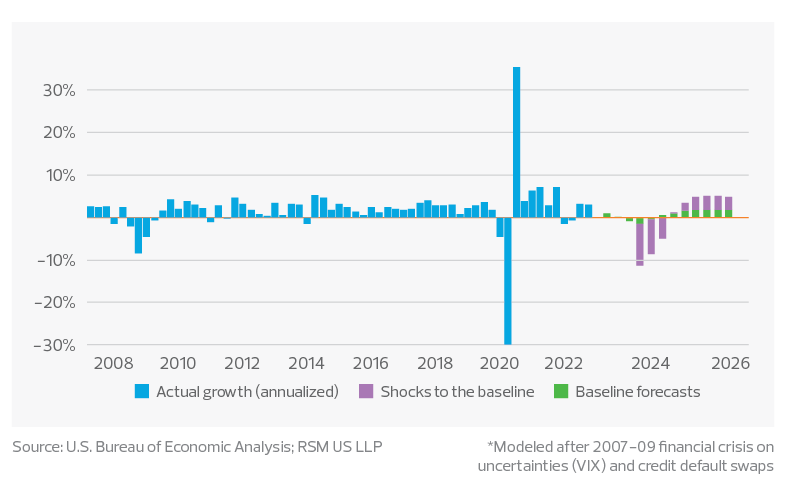

An actual default's impact on GDP growth*

The economy would immediately sink into a deep recession in the following quarter, with a decline in gross domestic product exceeding 10%. The recession would last into next year before an economic rebound in 2025. In that scenario, total GDP loss would approach $700 billion while 11 million jobs would be lost.

The key difference between the current situation and the financial crisis is that the economy is on a trajectory to experience a mild recession during the second half of this year, while inflation remains at a multidecade high. The policy tool set to fix a deep recession today is therefore limited, and the probability of self-induced deep recession would increase substantially.

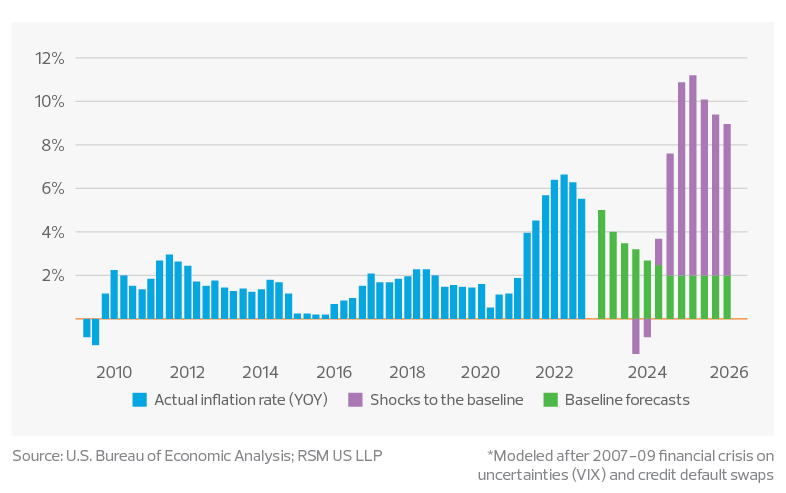

An actual default's impact on PCE inflation rate*

As uncertainties and credit default swap rates rose, the first-order effect on pricing would be a sharp fall in the overall inflation rate. The model, however, assumes that both monetary and fiscal authorities would swiftly reduce the federal funds rate and increase fiscal support. This time around, though, reducing the federal funds rate may not prove sufficient to bring down long-term interest rates.

While both the monetary and fiscal actions would eventually lift the economy out of a recession, the inflation costs would be immense. Built upon the current level of sticky inflation, inflation could reach above 10% as the economy bounces back from the aftermath of the deep recession.

Still, we believe there is a less than 10% chance of a full-scale payment default. A more likely scenario, while undesirable, is a situation like 2011, when the negotiation over the debt limit went down to the wire.

If that happens, the GDP costs would be up to $200 billion, and 4 million jobs would be lost.

In both scenarios, we do not assume a lasting default on U.S. government debt, which would be much more devastating.

It is important to bear in mind that the two scenarios we have modeled, a technical default versus a full-scale default, are based on historical events and are intended to provide benchmarks for evaluating the potential consequences of a default.

But no two crises are identical. With the current state of the economy, in which inflation is constraining both fiscal and monetary policy, we anticipate that our estimates of GDP declines, the number of lost jobs and the unemployment rate could be subject to upside risks.

The takeaway

The debt ceiling standoff is already raising the cost of doing business through an increase in the cost of issuing debt by both public and private actors.

While our baseline forecast indicates that a true catastrophe will be averted at the last minute, the idea of a relatively benign outcome similar to the 2011 crisis would appear to be somewhat of a rosy scenario given current conditions.

If the policy brinkmanship fails to produce a compromise, there would be a significant impact on overall output, inflation and employment.

Small and medium-size enterprises that do not have the resources to survive such a crisis are especially prone to insolvency risks under such conditions. In the end, households would bear the burden of a failure on the part of the American political authority.

RSM contributors

The debt ceiling sets a limit on how much debt the U.S. government can incur. It dates to 1917, during World War I, and was refined during the 1930s—two periods of elevated federal government expenditures.

In January, the U.S. government exceeded the $31.4 trillion debt limit set by Congress, kicking off a series of moves by the Treasury to fulfill the government’s obligations.

At some point, though, the Treasury will exhaust what it can do, and, without a debt limit increase, the government will enter default. When that happens depends on the flow of revenues into the U.S. Treasury.

The Congressional Budget Office said in February that the date of an actual default would fall sometime between July and September.

The Treasury has two effective means to stave off default: cash on hand in its Federal Reserve account, which was approximately $455 billion near the end of January, and financial maneuvers known as extraordinary measures.

About 24% of total debt is in nonmarketable securities, mostly consisting of the so-called government account series for federal pensions and other agency holdings. The Treasury temporarily withholds payments into these funds to postpone the so-called X-date when default on marketable securities begins.

Seventy percent, or $16.7 trillion, of U.S. marketable debt is held domestically; of that, $11.2 trillion, or 47%, is held by the public and $5.5 trillion, or 23%, is held by the Federal Reserve.

The overwhelming majority of Fed holdings is part of the quantitative easing program put in place in the financial crisis and then resurrected in response to the pandemic.

Japan has long been a major holder of U.S. debt and has the largest share (15%) of U.S. debt held by foreigners.

Japan’s interest in U.S. securities is a function of U.S.-Japanese trade and investment relationships as well as Japan’s perennially low interest rates compared to the return on U.S. investments.China, with 13% of total foreign holdings, and the United Kingdom, with 9%, are second and third, also likely byproducts of trade as well as London’s role as a financial center. These are followed by smaller nations, many of which are financial centers.

One challenge to the current round of policy brinkmanship is the lack of viable options to defuse the standoff. The following is a quick synopsis of options that could avert a crisis:

Discharge petition: One potential solution would be through Congress, where a simple majority, without support of leadership, brings a bill for lifting the debt ceiling to a vote on the floor. It is unclear whether GOP members, who hold the majority in the House, are willing to defy party leadership to use that procedure. In addition, such an action can be quite time-consuming and would be unsuitable as a last-minute solution.

Prioritization: Various plans are circulating that would prioritize Treasury payments to avoid a default. Both parties have studied such an approach, which would involve picking winners and losers during an extended standoff. The idea that the U.S. government would choose to pay foreign holders of debt or large financial firms—the five largest private sector holders of public debt own about 5% of total debt worth $1.2 trillion, according to Bloomberg—over Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid recipients strikes us as fanciful at best.

Platinum coin: One of the odd talking points around the debt ceiling debate involves the Treasury minting a trillion-dollar coin and depositing it into its account at the Federal Reserve. Because of a quirk in the law, the face value of coins minted by the Treasury is not limited. We doubt this would survive legal much less political scrutiny, and it is a general nonstarter as a viable solution.

Fourteenth Amendment: The “validity of the public debt of the United States … shall not be questioned” is part of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. One interpretation of this is that nonpayment of public debt is not constitutional.Since this has little jurisprudence around it and the prevailing legal interpretation is divided, we do not expect much political capital to be used on this option in the run-up to the more intense phase of this crisis through midyear.