The labor market's recovery from the pandemic has been nothing short of remarkable. Most of the staggering number of job losses have been recovered, and the unemployment rate is near its pre-pandemic low.

But sometimes, in economics, there can be too much of a good thing. In this case, it's the demand for workers, or, to put it more accurately, an excess demand for workers.

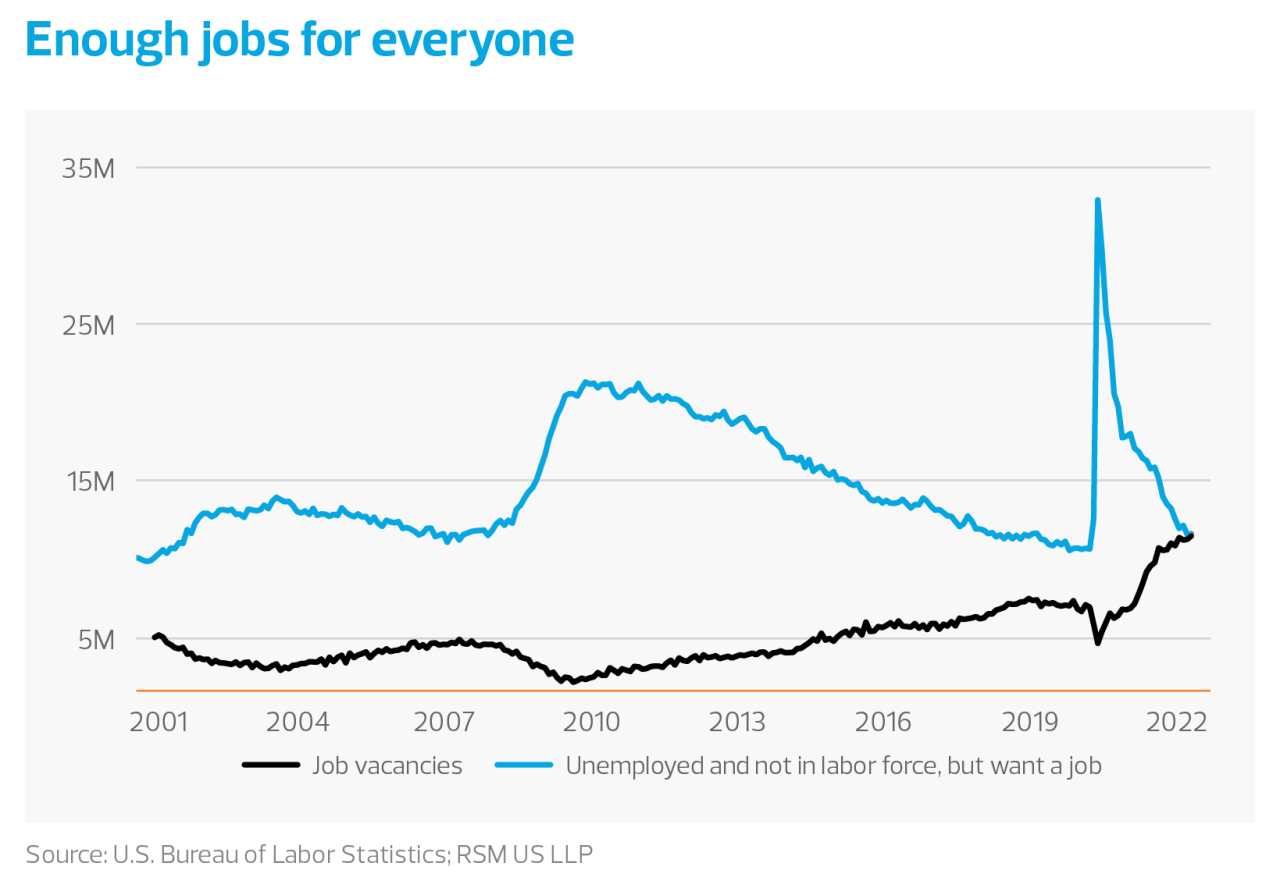

The economy is fewer than 1 million jobs from reaching its pre-pandemic level. Yet there were a record 11.55 million job vacancies—a proxy for labor demand—reported in March, according to government data.

That's because as strong as the economy has been, companies today are facing a harsh reality: The rapid growth of the past year won't come back anytime soon.

Yet many companies are planning to hire workers as if such growth is sustainable.

Although there are signs that companies are adjusting, especially as equity markets retreat, many companies have yet to get the message. And the scramble by companies to find workers—or simply to keep the ones they have—leads to higher wages, which in turn, leads to higher inflation.

The result is the stunning number of job vacancies as workers continue to quit their jobs at historically high rates.

The squeeze is made worse as workers who have been on the sideline since the start of the pandemic have been slow to come back to the labor force.

In a sense, it's a virtuous circle gone wrong as labor demand spirals out of control. Then, it is no surprise that Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell said that the labor market is at a "tight to an unhealthy level"—hardly the characterization a Fed chairman usually utters in a strong economy. It is clear forward guidance for the market to start reacting as the Fed moves to put an end to an era of near-zero interest rates.

We believe this imbalance should prompt companies to reassess their growth potential, and as a result, their demand for labor.

Such a reassessment, in fact, might work in the Fed's favor as a major decline in labor demand might take place before interest rates are brought back to neutral, potentially in the second half of the year or early next year. The decline will most likely be a sharp one, but it is inevitable and necessary.

An unrealistic level of labor demand

Behind the surging labor market is an overheating economy. Last year, elevated spending and economic growth rates contributed to a significant increase in corporate profits, rising by 20.97% in the fourth quarter on an annualized basis. That bullish sentiment spilled over to outsized gains in the equity markets.

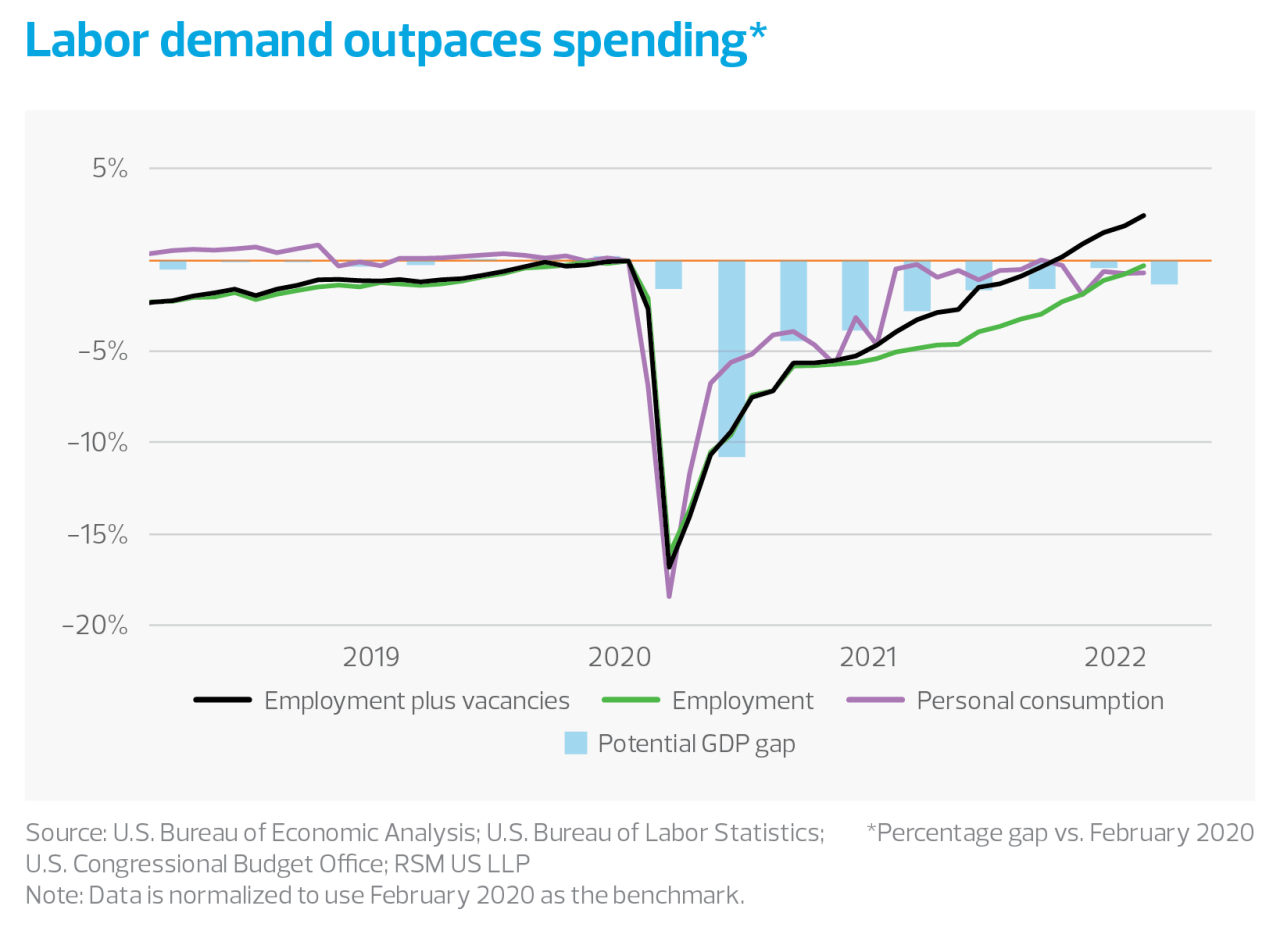

So, companies reason, why not keep a good thing going? The expectation for further growth, especially when order backlogs remained historically high because of global supply chain issues, pushed labor demand to outpace personal spending and even overall gross domestic product last year and continued in the first quarter.