In response to combatting Australia’s COVID-19-induced recession, two significant income tax measures, instant asset write-off, and tax loss carryback were announced as part of Australia’s October 2020 federal budget. These temporary measures (expiring on June 30, 2022) are designed to inject cash into the Australian economy by lowering corporate tax collections with the aim of increasing employment and incentivizing businesses to spend money. There are eligibility criteria and anti-avoidance rules to navigate, so taxpayers looking to take advantage of these measures should seek guidance from Australian tax advisors.

Instant asset write-off

Australia’s capital allowance rules provide depreciation deductions for acquired assets over the asset’s determined effective life or at a statutory effective life cap for certain asset categories.

Australian taxpayers who acquire depreciable assets from Oct. 6, 2020, and install them by June 30, 2022, will be entitled to a 100% instant asset write-off for tax purposes. There is no cap on the cost of the asset. However, there are exceptions, which include:

- Capital works (buildings and structural improvements)

- Software allocated to a software pool

- Assets to be predominantly used outside Australia

Taxpayers who are members of a group with global turnover in excess of AUD$5 billion are not eligible for the instant asset write-off. However, taxpayers falling within these criteria will still be entitled to the instant asset write-off if their Australian taxable income is less than AUD$5 billion and they have invested more than AUD$100 million in tangible depreciating assets between July 1, 2016, and June 30, 2019.

Australian taxpayers who acquired depreciable assets with a cost of up to AUD$150,000 between March 12, 2020, and Oct. 6, 2020, and install the assets before Dec. 31, 2020, are also entitled to an instant asset write-off. However, this measure does not apply to taxpayers who are a part of a group with global turnover in excess of AUD$500 million.

Tax loss carryback rule

Australia’s tax year runs from July 1 through June 30 of the following year. However, Australian corporate taxpayers may apply for a substituted accounting period ending on a date other than June 30. Most Australian subsidiaries of a U.S. parent have likely applied for a December 31 substituted accounting period to align the Australian tax year-end to that of the U.S. parent. This is particularly true if the U.S. parent has subpart F or Global Intangible Low Tax Income (GILTI) inclusions.

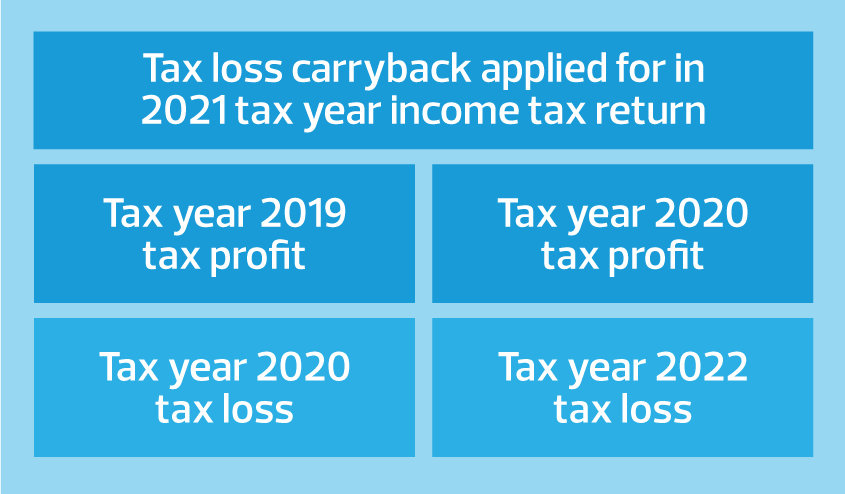

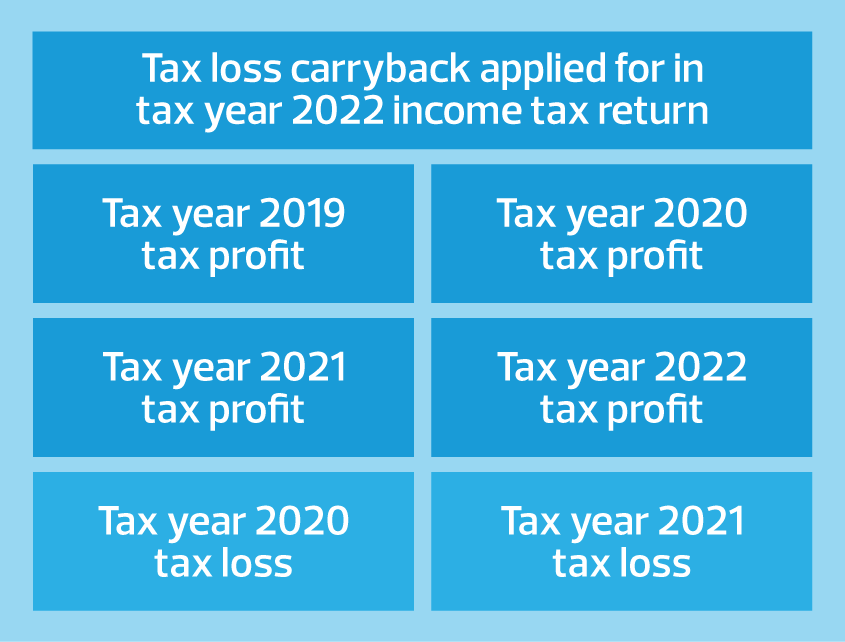

For the tax year 2021 (fiscal year ending [FYE] June 30, 2021, or Dec. 31, 2020), Australian corporate taxpayers can elect to apply their tax losses for the 2020 tax year (FYE June 30, 2020, or Dec. 31, 2019) and 2021 tax years against tax profits from the 2019 tax year (FYE June 30, 2019, or Dec. 31, 2018) or 2020 tax years.