Housing's lagging reaction to rate increases will make the Fed's job more complicated for months to come, even as housing inflation eases as anticipated.

Key takeaways

While there are signs of inflation slowing, it will most likely not go back to the target rate anytime soon, which supports our forecast of a 3% core inflation rate by the end of next year as the economy continues to transition to a higher-priced environment.

A correction in the housing market as mortgage rates reach 20-year highs is underway. While overall price growth has cooled, though, the housing components of the two inflation reports—the consumer price index and the personal consumption expenditures price index—have shown no signs of peaking.

We estimate an approximately 18-month lag between changes in housing prices and in the housing components of inflation. That means we do not expect housing inflation to peak until the third quarter of next year or to fall to the pre-pandemic level until late 2024.

The Federal Reserve will almost certainly need to lift its policy rate above 5% and be prepared to hold it there, because inflation driven by housing tends to be persistent.

Housing inflation: Long and variable lags

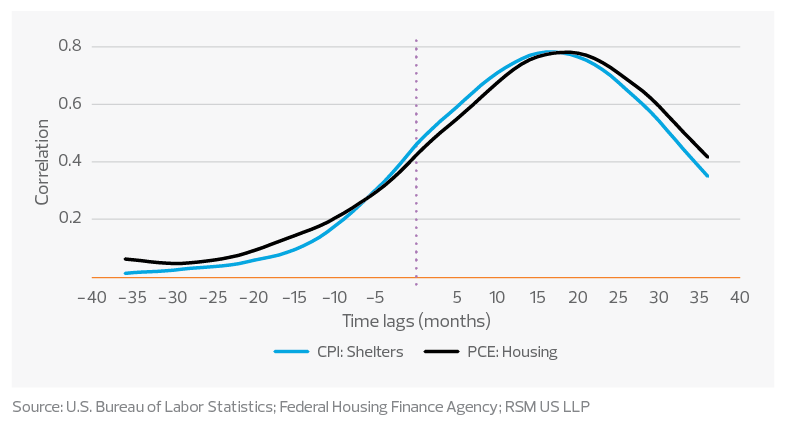

We used more than 20 years of historical data to estimate the correlation between current housing inflation and past housing price growth.

The results show that housing inflation in the consumer price index can be best predicted using data on housing price growth from 17 months prior, and in the personal consumption expenditures index from 19 months prior. There is roughly an 18-month to two-year lag before policymakers can assess the impact of changing housing prices and inflation.

The correlations are also strong between housing prices and the housing components of inflation reports, suggesting that housing price growth can be a reliable predictor for housing inflation despite the different methods used to calculate the two series.

First, we track the correlation between the two:

Correlation between housing prices and housing component of inflation reports

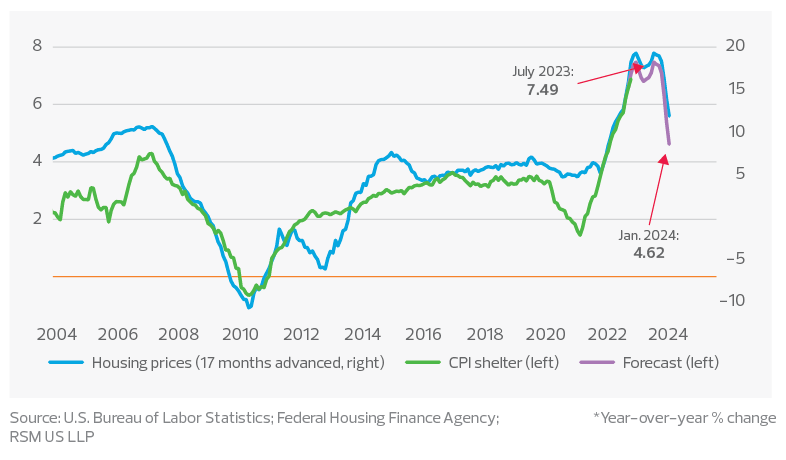

Then, we can forecast the housing inflation components for both the CPI and PCE reports:

CPI shelter component and housing prices*

PCE housing component and housing prices*

At their peaks in the third quarter next year, the year-over-year housing component growth rates would be 7.49% for CPI and 7.4% for PCE.

Those would translate to 2.4 and 1.3 percentage-point contributions to overall CPI and PCE inflation, respectively.

By the first quarter of 2024, housing inflation from both reports would be 4.62% and 4.57% for CPI and PCE, respectively, remaining substantially elevated above pre-pandemic levels.

Policy implications: Lift and hold

With housing accounting for the largest portion of total consumer spending in both inflation reports—more than 32% in CPI and 17% in PCE—we expect inflation to stay sticky throughout next year, especially core inflation, which strips out the more volatile food and energy prices and affects the central bank’s policy path.

The Fed has signaled it will consider the lagging impact of monetary policy, particularly regarding the housing market, to determine the pace of its rate increases.

While we acknowledge that anecdotal evidence now shows rents possibly peaking, our interpretation of the data suggests that to pause or pivot on rate hikes would most likely result in a series of stops, starts and reversals in the policy path.

In the end, that approach would prove unproductive and put the anchoring of medium- to long-term inflation expectations at risk.

Long and variable lags associated with housing inflation should concern the Fed in two ways:

- Transparency: The lags add to the risk of higher and more entrenched inflation expectations that would prove difficult and costly to roll back. Given that the economy would have experienced high inflation for more than two years by the time the housing components peak later next year, such a sustained period of high inflation further erodes the already strained credibility of the central bank. We think the Fed will have to be more transparent about its policies should inflation remain elevated—which seems likely, based on our research.

- Reaching the target: As housing price growth remains above the pre-pandemic level, returning to the Fed’s target of 2% inflation would require more work from the central bank. That means more rate hikes to come—or, as Chairman Jerome Powell said Nov. 2, "Some ways to go." And with inflation most likely remaining elevated for longer, the probability of a lift-and-hold monetary policy over the next 12 months, perhaps well above our current range of 5% to 5.2%, looks a lot higher.

The takeaway

Housing's lagging reaction to rate increases will make the Fed's job more complicated for months to come, even as housing inflation eases as anticipated.

While there are signs of inflation slowing, it will most likely not go back to the target rate anytime soon, which supports our forecast of a 3% core inflation rate by the end of next year as the economy continues to transition to a higher-priced environment.