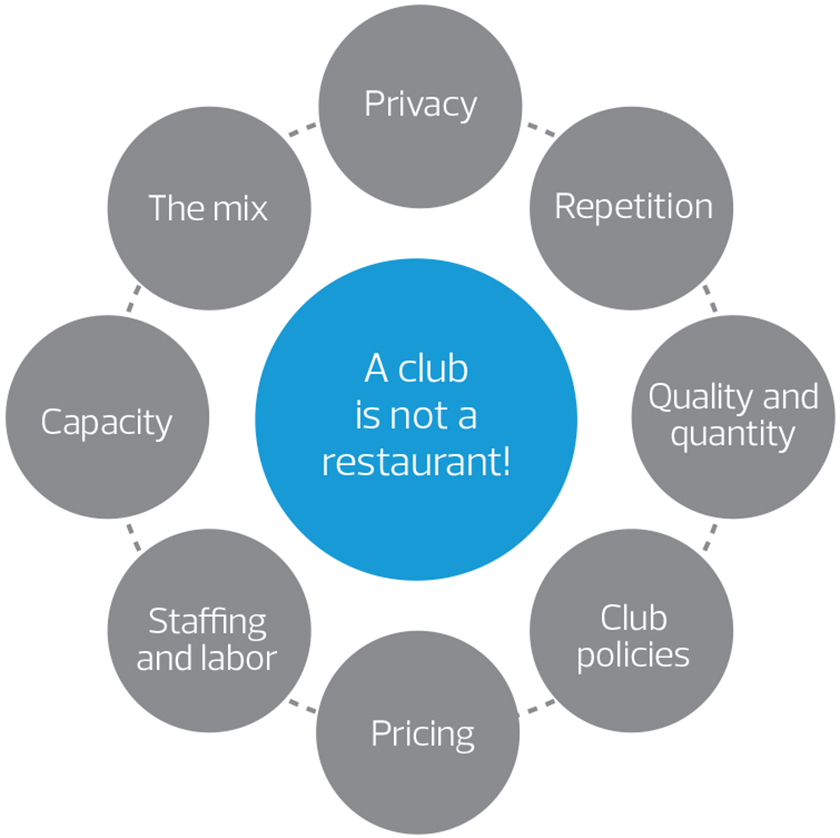

Privacy at a price

The clue is in the name. Private clubs, and their dining facilities, are not open to the public. Privacy—or exclusivity, as some would say—is a primary reason members join in the first place, and that privacy comes at a price. While a public restaurant is open to anyone prepared to pay its menu prices, a club’s customer base is essentially capped at its number of members plus their guests. If a club has 750 members, then its customer base is 750 families. Given that the number of potential diners at a club is fixed, the implications for revenue are obvious. In a recent report on club food and beverage revenues, the figures were flat for the past five years—including 2020 and 2021, when the pandemic was at its peak.

Repetition

According to Mark Twain, “History does not repeat itself, but it does rhyme.” This maxim holds true for clubs faced with the challenge of continually reselling members a dining experience that may vary slightly but remains essentially the same. Unlike a restaurant on Main Street, which may never see a transient customer again, club dining facilities primarily host repeat customers, who bring high expectations and endless critiques. For this reason, clubs must pour resources into getting things right every time, from both a labor and a product perspective, while also allowing for occasional substitutions and add-ons to menu offerings on member request—without charging extra for the inconvenience or additional ingredients.

Competitive pricing

If the number of diners, and the share of membership fees subsidizing dining costs, are essentially fixed, can revenue be grown by increasing menu prices? Not really. Clubs operate in the same competitive marketplace as restaurants, and aggressive menu pricing will likely result in the club hemorrhaging revenue dollars to neighborhood restaurants or, more likely, cause an insurrection among members.

Like most consumers, even those in upper-income brackets, club members tightened their belts throughout the recent economic slowdown. Further, they have already paid sizable membership dues and generally expect the club’s menu prices to represent exceptional value. It is always worthwhile for clubs to compare their menu prices to those of a local restaurant offering a similar dining experience to confirm that value.

Value also comes into play in subsidized members-only events, such as New Year’s Eve, Valentine’s Day, and seasonal activities. Food costs at some of these events can exceed 100% of the funding available through club dues and event registration fees. But how many members would you lose if you didn’t host the event or charged a non-dues-subsidized price? Member events are essential offerings at most clubs, and even with careful budgeting, management often must subsidize them with member dues. Smart planning and transparency are key to members’ acceptance of this economic reality.

Quality and quantity

If a price comparison of a club dinner to a restaurant equivalent does not point out the value of club dining, then a tasting probably should. Clubs typically serve better-quality products—fresh produce as opposed to frozen, baked rather than purchased bread—and more generous quantities. This is true not only for a la carte dining but also for the club buffet, which typically carries high-quality products and provides quantities that are overestimated to avoid shortfalls.

As for alcohol, most club members would be hard-pressed to recall the last time a jigger was used in a club bar. Free pours from a heavy-handed bartender are more the norm, and cocktails are often served in wine goblets or beer glasses. This tradition presents clubs with unique challenges in protecting the bottom line. As with food, aggressive pricing is not really an option, and neither are some of the “tricks” used in the restaurant trade to maintain profitability. Members will be highly resistant to portion control, weaker drinks, cheaper ingredients, or low-end consumables.

Capacity

Clubs tend to have excess capacity for a la carte dining but not enough for large-scale member events. They also have multiple and competing dining outlets, such as a formal dining room, grill room, and pool café, even though it is only possible for a member to utilize one at a time. Each outlet has its own storage area, kitchen, and staff, which all carry a cost. Hence fixed revenue dollars are spread across multiple outlets. Restaurants, by contrast, usually have a single dining room and kitchen and, of course, a larger customer base.

Staffing

Club members expect a “creative” rather than a “manufacturing” kitchen. While restaurants tend to use hourly line cooks, clubs frequently employ highly trained executive and sous chefs plus specialized staff, such as sauciers, pastry chefs, and sommeliers, all of whom are typically full-time salaried employees who remain on the payroll through slower seasons.

Maintaining adequate staffing in the dining room is often a challenge due to prohibition on cash tipping. Clubs may have to pay a higher hourly rate or offer more overtime than competing restaurants in order to attract and retain service staff to offset the lack of tips. Another cost factor is that members are rarely required to make reservations for lunch or dinner—leading clubs to overstaff in case everyone turns up for Friday night dinner.

Club policies

Members who prefer to spend $400 on dinner for two while wearing jeans should probably go to the local restaurant rather than the club. Dress codes are among the few topics likely to spark more lively debate in a board meeting than food and beverage subsidies. However, in today’s time-constrained world, it is worth noting that formal dress codes and prohibitions on electronic devices often discourage members from frequenting the dining room.

In the mix

The typical activity and product mix at clubs is not conducive to turning a profit in the food and beverage department. Clubs do more business at lunch than dinner, and lunch menus are always more competitively priced. In addition, less beverage is consumed at lunch, which is unfortunate from a profitability standpoint. While the most profitable meal for restaurants is breakfast, clubs typically have minimal breakfast traffic, and “gratis” breakfast items are quite common.

Turning to member events, again, if your club hosts a significant number of them, consider your pricing strategy carefully and its impact on food and beverage results overall.

Key questions to consider:

So the next time a new candidate for the finance committee claims to have made a fortune owning a restaurant and promises to “fix” the club’s food and beverage operation, ask them these five questions:

- Did your restaurant serve only 750 families?

- Did you regularly throw lavish parties for those families and charge them only a fraction of market price?

- Were your alcohol pour sizes often double that of other restaurants?

- Did you accommodate all diners’ requests for menu substitutions and customizations without charging them extra?

- Did you have an executive chef, rather than a line cook, whose payroll you had to carry during the off-season just to retain their talent?

A candidate who can answer yes to all five indeed has a unique set of skills.

The reality, however, is that a club is still not a restaurant. Unless critics of club food and beverage results are willing to step inside the circle of truth and accept the realities of the operation before attacking management, they do not deserve a seat at the table.

Management should still be held accountable for results and be expected to continually improve. But the budgets to which management are being held accountable must be based on fact, not fiction, and address operational realities. Budgeting a flat 50% blended food cost for every month, when you know some months will include member events with 80%, 90%, or even higher food costs, is simply an exercise in futility.

In a recent food and beverage operational audit of one club, RSM found that 20% of the club’s food revenue was related to member events, and the pricing philosophy for events was to achieve a food cost of 50%. However, on review of 10 member events, we found an aggregate food cost of 69%.

Conclusion? The budget was a flawed, unrealistic document that did nothing more than quantify the wishful thinking of club leadership and management.

To summarize, the reason clubs “lose” money in food and beverage is because the dining room is a member amenity—just like the golf course, tennis courts, fitness center, and swimming pool. How much money did the club “lose” on its golf course last month? Probably more than it did on food and beverage.

Rather than explaining why the club is “losing” money on food and beverage, the time has come to question the premise that money is even lost. All club amenities carry a cost, which is why clubs charge dues. A portion of every dollar in dues goes to subsidize the food and beverage operation. If you want to lower that number, start by taking away member events—which will reduce not only your subsidy but also, no doubt, the number of members in your club.