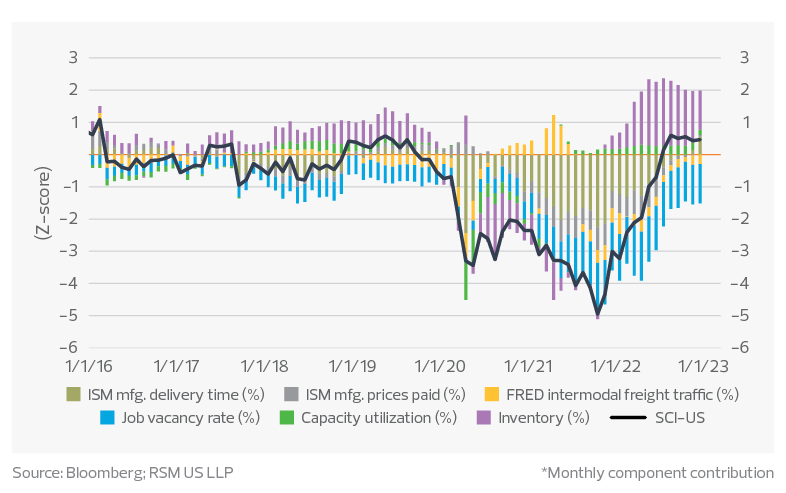

In addition, some of the rapid growth last year was the result of base effects in the data, or comparisons to the low levels of 2021. Because supply chain issues continued last year, these issues will most likely play a part in the rate of growth this year.

On top of that, as the inflation and job components of the supply chain index most likely remain underwater for the foreseeable future, a potential swing in inventory to the downside because of excess supplies and slowing demand could cause the U.S. supply chain to contract again.

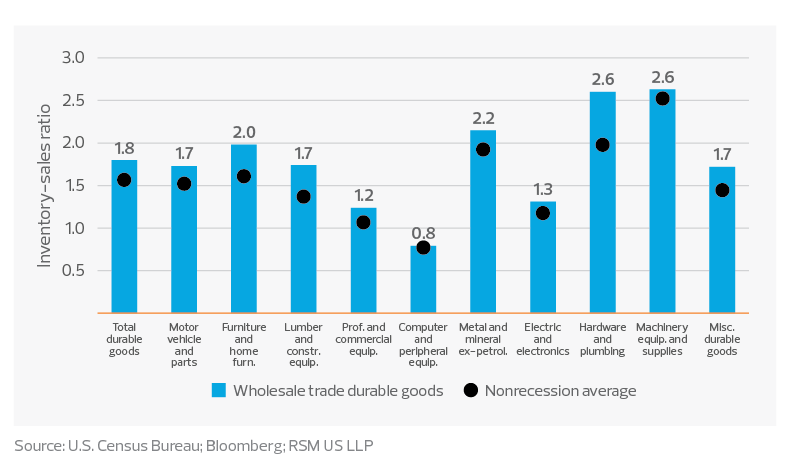

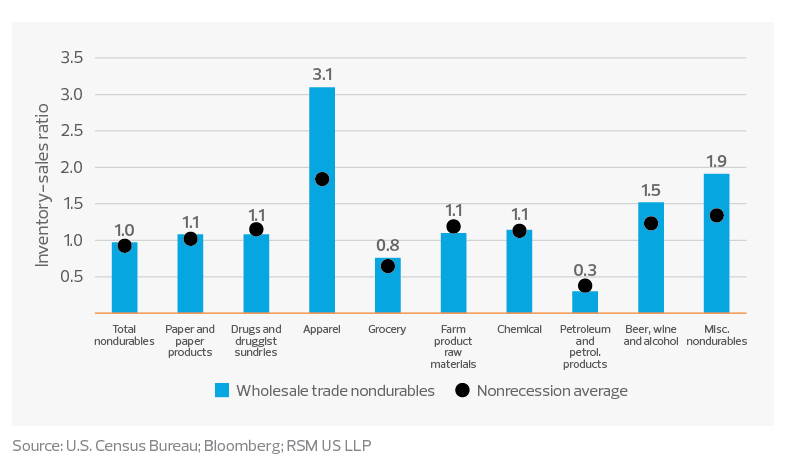

A breakdown of inventory growth by industry gives a clearer picture of the state of the supply chain.

Most important, as business cycles approach their end,large firms sometimes engage in what is known as channel stuffing, which tends to end up harming small and medium-size firms.

Channel stuffing is an attempt to inflate bottom lines by filling distribution channels through excess inventories to meet quarterly sales targets well ahead of actual demand.

While we have yet to observe blatant channel stuffing in the current cycle, it is worth flagging given the general uncertainty over demand.

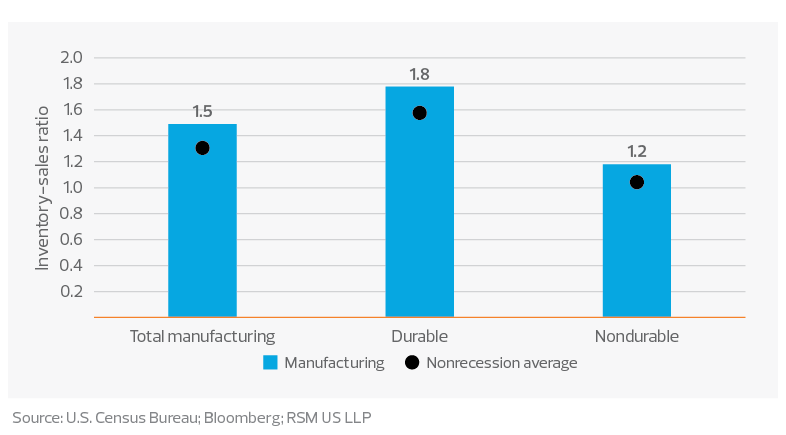

Inventory-sales ratio overview

Another way to look at inventory accumulation is to standardize each industry by the ratio of inventories to sales.

Over time, manufacturing and trade firms would be expected to optimize their levels of inventory to meet the demand of their customers.

As we show, inventory-sales ratios declined on trend from 1992 to 2007 as the global supply chain increased efficiency, making just-in-time production and inventory minimization possible.

And during economic downturns, sales would be expected to fall while some basic level of inventories was maintained.

This would tend to push inventory-sales ratios sky-high during recessions and keep them higher than normal during periods of reduced demand, as happened following the financial crisis.