Looking to alternatives

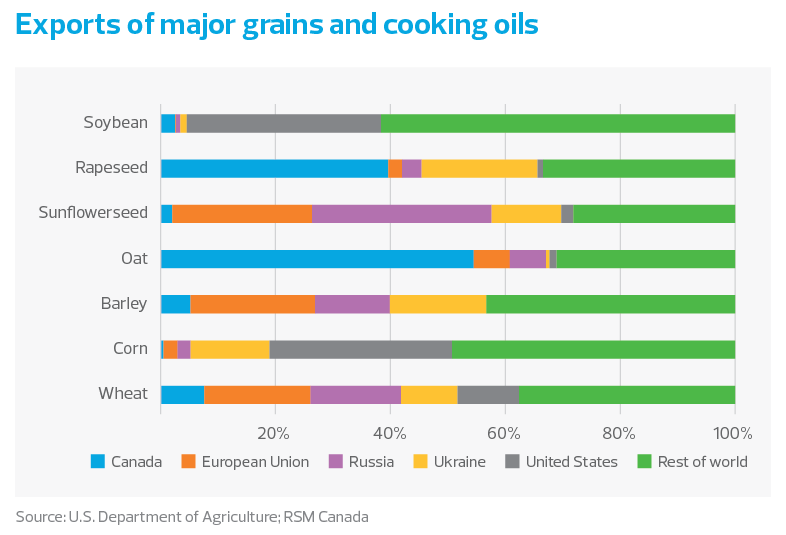

But there are alternatives. The United States and Canada produce and export many of the same agricultural commodities or close substitutes for products that Russia, Ukraine and Belarus produce.

Canada, for example, is also home to the largest potash mine in the world. The United States makes up 30% of global corn exports, while Canada makes up over half the global oat exports.

Similarly, Canada is the largest exporter of canola oil, and the United States and Canada are large exporters of soybean oil, a substitute for sunflower oil.

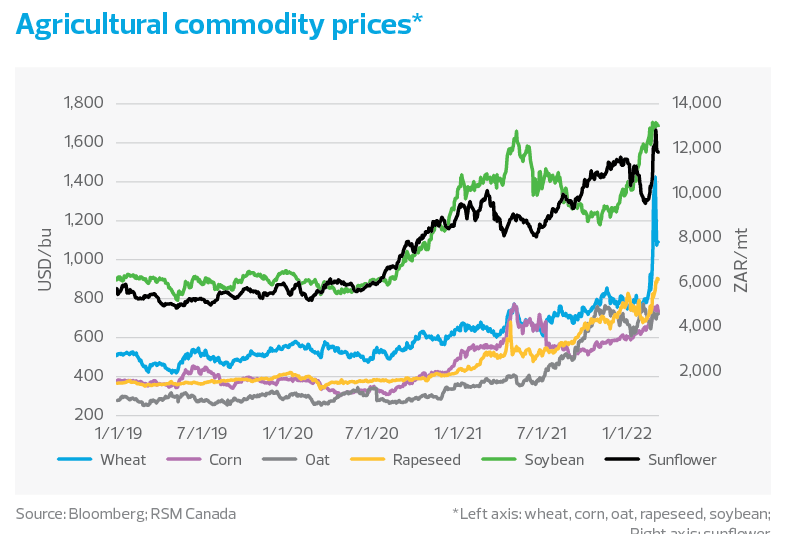

North American agricultural commodity producers stand to benefit from higher prices given high demand and strained supply abroad. Already, European companies are looking to secure potash contracts in Canada.

But even if North American producers can bridge some of the gaps, livestock farmers and food manufacturers will face higher prices.

Consumers, in turn, will pay more. Food inflation will soar above last year’s levels, with middle- to low-income households hurt the most as their tight budgets are squeezed.

North America’s role

Even as many countries around the world will face food shortages, North American consumers do not have this risk. The United States and Canada, which produce more food than their populations consume, are net food exporters.

That’s not the case in the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia, which must import food to meet their domestic needs and rely heavily on supplies from Russia and Ukraine.

Without adequate grains and cooking oils, millions who are already at risk will go hungry as the crisis persists.

That’s where the U.S. and Canadian agricultural commodity producers can step in. If they can increase production and exports, especially grains, cooking oils and potash, they will help alleviate global food insecurity.

Achieving this increase in production will require a significant commitment. North American commodities could be more expensive for foreign markets because of higher labor costs, and production costs are still rising along with energy prices. There are also logistical challenges associated with altering the flows of trade, further complicating the already-strained global supply chain.

In addition, climate change presents another challenge; grain production in the United States and Canada hit record lows last year because of extreme weather events, and that trend is expected to continue. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has warned that climate change is harming global food supplies faster than nations and producers can adapt, threatening the era of consistently high crop yields.

The takeaway

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine risks destabilizing global food markets by disrupting production and trade flows. For consumers and businesses in food production and manufacturing, high food inflation adds to the plethora of challenges, including energy prices.

But agricultural commodity producers in North America could play a key role in alleviating global food insecurity by increasing exports while at the same time netting economic gains.

Businesses need to look ahead and prepare accordingly, whether by increasing production or securing future contracts as global food supplies are disrupted into next year.