Providing enough affordable housing for all Americans would not only address rising housing costs, but also increase the availability of decent shelter.

Key takeaways

Local and federal governments must redesign policies that incentivize more supply while keeping prices down.

Only then will the market provide the 1.7 million homes a year needed to meet the growing demand of a rising generation.

Over the past 15 years, the United States has not built enough homes to keep up with growing demand. The problem has intensified during the pandemic, with demand skyrocketing because of the shift to working from home and the availability of historically low mortgage rates.

We estimate that at the end of 2021, the United States was about 3.5 million homes short of the number required to maintain a stable market.

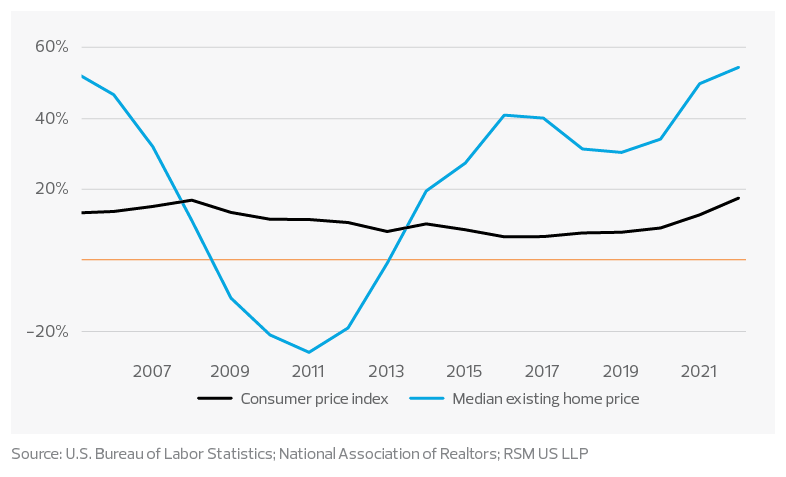

Together with the rising cost of building materials, the depleted supply of new homes has pushed housing prices to record highs, contributing to a rate of inflation not seen in more than 40 years.

To close the gap, the U.S. housing market will need 1.7 million new homes on average each year until 2030, according to our estimates. This figure is calculated based on current economic conditions, cost of living and a long-term growth forecast of 1.8% annually.

Given that there were only 1.6 million new housing starts last year, when the market was booming, it would be impossible to rely on the private sector to deliver such a high level of new homes each year, especially as the market for housing has cooled sharply.

We believe government agencies at the national and local levels need to take a more active role to overcome the current housing deficit, by adopting policies that include more flexible zoning restrictions, expanded housing tax credits, and provisions that broaden affordability.

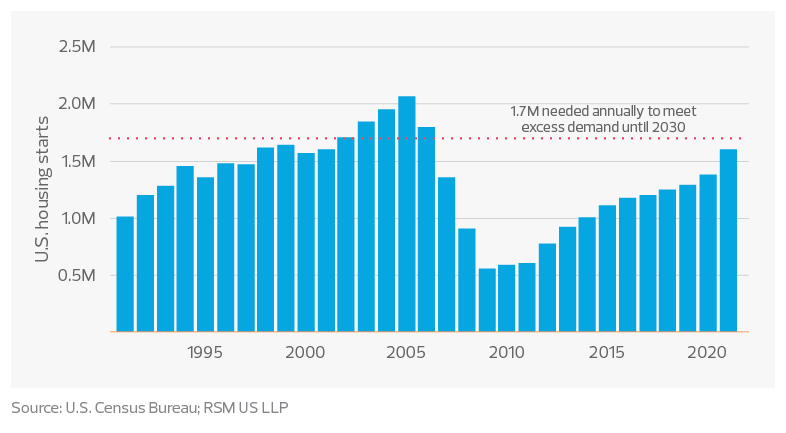

U.S. housing starts–annually

Forecasting housing demand

The collapse of the housing market during the 2008-09 financial crisis not only slowed demand for new homes, but also made builders wary about being too aggressive. Sentiment among builders plunged so low that it did not recover until 2017.

From 2007 to 2020, new housing starts—a proxy for new housing supply—never crossed the 1.5 million mark, which was widely estimated to be the average annual supply needed to meet target household demand in the 2010s.

This resulted in a growing housing deficit that reached 3.8 million units by the end of 2020, according to a recent report from Freddie Mac, a figure we used as a benchmark to then calculate the 2021 deficit.

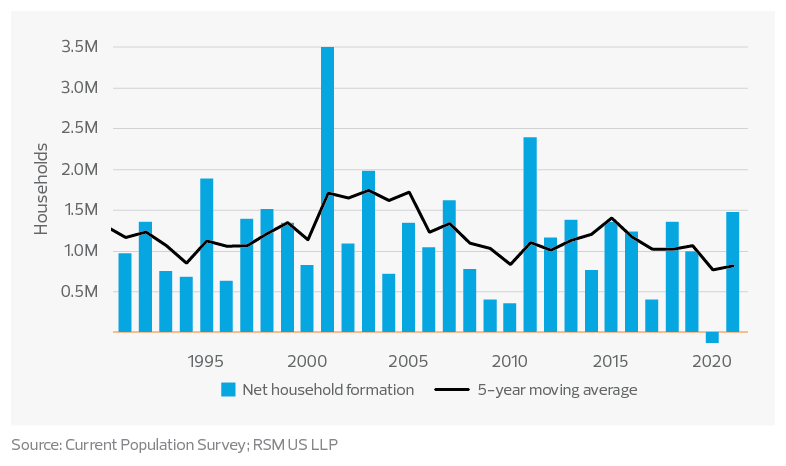

The long-term supply to meet household demand through 2030 in our base case is 1.3 million units each year. This figure includes 900,000 units for newly formed households annually, and is consistent with the five-year average of net household formations from 2016 to 2021, according to data from the Current Population Survey of the U.S. Census Bureau.

U.S. net household formation

The estimate for new household formations is also in line with Freddie Mac's lower bound forecast for housing demand in the 2016-2025 period. The lower bound was based on the assumption that the cost of living for households in 2025 would be 20% higher than before 2016, and that higher living costs have been found to discourage household formations.

The assumption is not far off, as the five-year change in the consumer price index reached 13% in 2021 and 17% in the first half of 2022. We expect inflation to persist in the second half of this year, especially regarding housing costs, which also hamper the formation of new households.

The other 400,000 units account for second-home demand, existing-home replacements and a healthy stock of vacant units, required to stabilize the market.

Change in cost of living from five years ago

The housing boom during the pandemic years, driven by steep rises in demand and prices, has helped incentivize builders to provide more new homes. The Census Bureau recorded 1.6 million new housing starts in 2021. That total included an extra 300,000 new housing units beyond the 1.3 million needed annually, pushing the total deficit from 3.8 million in 2020 down to 3.5 million units last year.

To completely close such a deficit and at the same time meet the new annual demand of 1.3 million new homes, the United States will need about 1.7 million units each year until 2030.

That said, our estimate would be subject to downside risks from rising inflation, which reduces Americans' desire to form new households. There is also the risk of an economic slowdown or even an outright recession as the Federal Reserve aggressively raises interest rates to tame inflation.

In the past two business cycles, net household formations dropped significantly during the recession years, falling to fewer than 1 million from 2007 to 2010, and even dropping to negative territory in 2020. The demand for new homes and the creation of new households often decline during recessions as personal incomes drop and spending falls substantially.

But even with an economic slowdown or potential recession in the coming months, construction of new homes will need to increase to close the existing gap. Deteriorating builder sentiment due to rapidly rising mortgage rates, which hit 5.65% as of June 17, and continued headwinds from labor and supply chain challenges are poised to limit new construction, exacerbating the housing shortage.

Closing the housing gap

The shortfall is in many respects an outgrowth of the financial crisis over a decade ago. The long-lasting impact of that crisis will not be fixed overnight and will require a sustained and balanced approach to increasing the housing supply. Two measures can help address the shortfall:

- Fix the zoning rules: First and foremost, zoning that limits construction needs to be relaxed and redesigned to reflect the changing demographics of those in need of housing.

- Expand affordability: Low-income housing tax credits and tax credits that support construction and redevelopment of homes under the Neighborhood Homes Investment Act need to be put in place through federal and state financing to address the affordability crisis.

Regulatory barriers around local and state economies will need to be reduced, and the affordability crisis faced by Gen Z and millennial cohorts needs to be immediately addressed. Both are necessary to promote generational economic equity and to relieve a housing shortage that is now contributing to overall inflation.

The takeaway

Providing enough affordable housing for all Americans would have a significant impact on the economy. Such an achievement would not only address rising housing costs, but also increase the availability of decent shelter, a goal currently unattainable for many Americans.

But the private market can’t do it alone—local and federal governments must redesign policies that incentivize more supply while keeping prices down. Only then will the market provide the 1.7 million homes a year needed to meet the growing demand of a rising generation.

RSM contributors

More from The Real Economy

The Real Economy

Monthly economic report

A monthly economic report for middle market business leaders.

Industry outlooks

Industry-specific quarterly insights for the middle market.