When will the economy support higher rates?

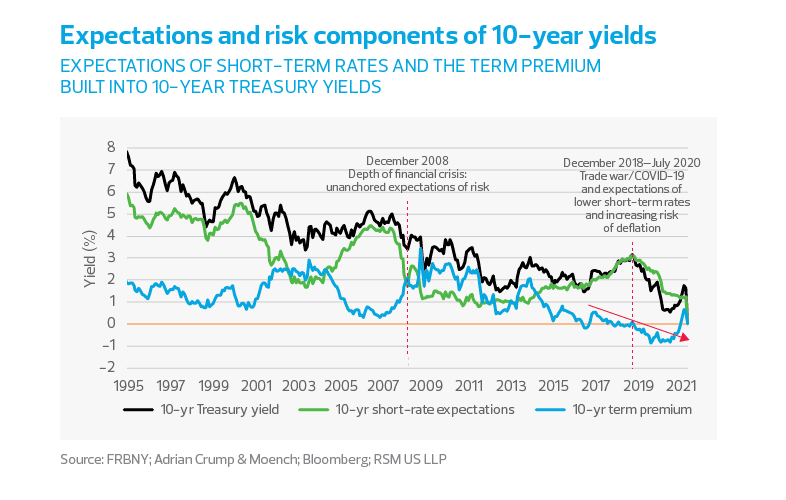

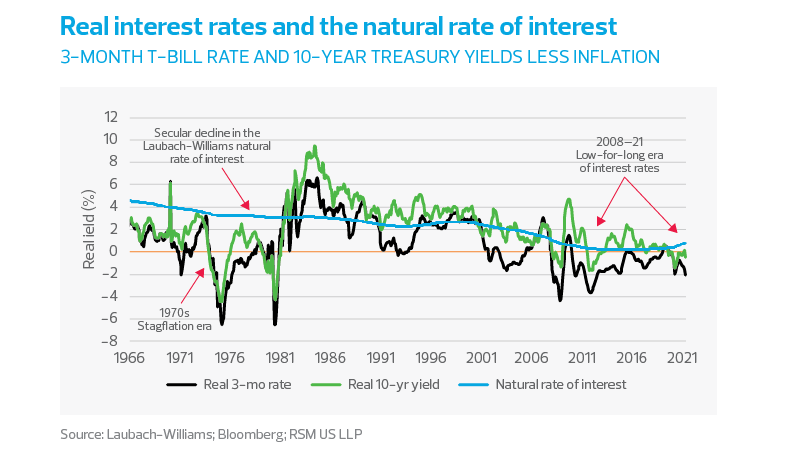

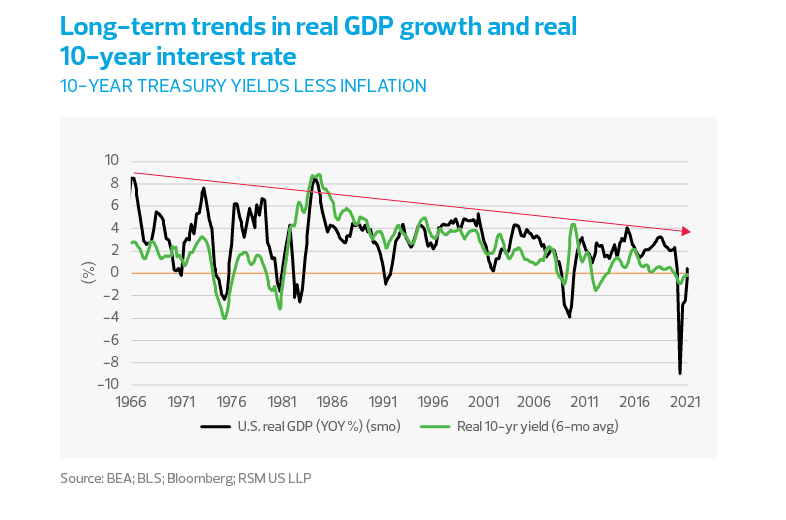

Because of the structural shifts in the global economy—automation, the advent of the global supply chain and the adaptation of inflation-targeting by central banks—the expected return on investment has trended lower. This is particularly the case in the aftermath of the global financial crisis and the Great Recession. The world’s developed economies arguably could no longer support the high real (inflation-adjusted) rates of return in earlier decades.

According to an analysis by Kathryn Holston, Thomas Laubach and John C. Williams at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, the natural rate of interest is defined as “the real short-term interest rate that would prevail absent transitory disturbances.”

Another analysis, by Thomas A. Lubik and Christian Matthes at the Richmond Fed, holds that the natural rate of interest is a hypothetical rate that is “consistent with economic and price stability.”

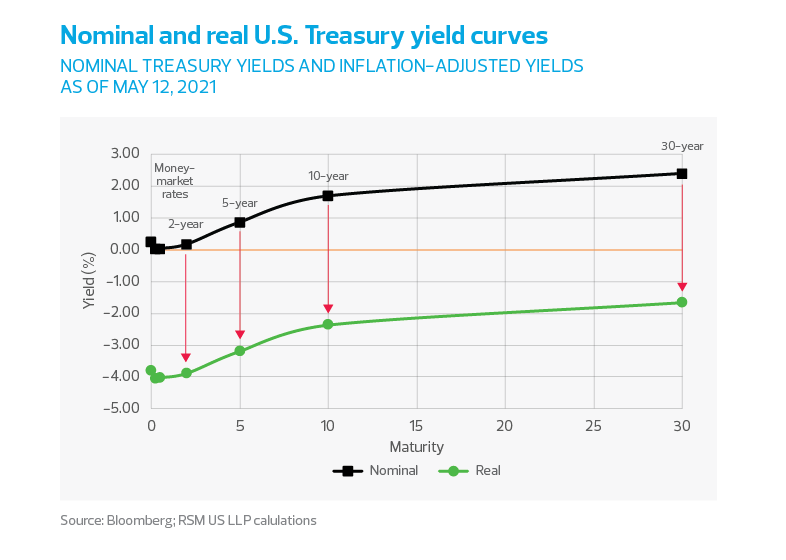

According to Holston, Laubach and Williams, the natural rate provides a benchmark for monetary policy. Real short-term rates below the natural rate indicate an expansionary policy, while real short-term rates above the natural rate indicate a contractionary policy. According to Lubik and Matthes, “it is not the level of the natural rate that matters, but its value relative to other interest rates.”

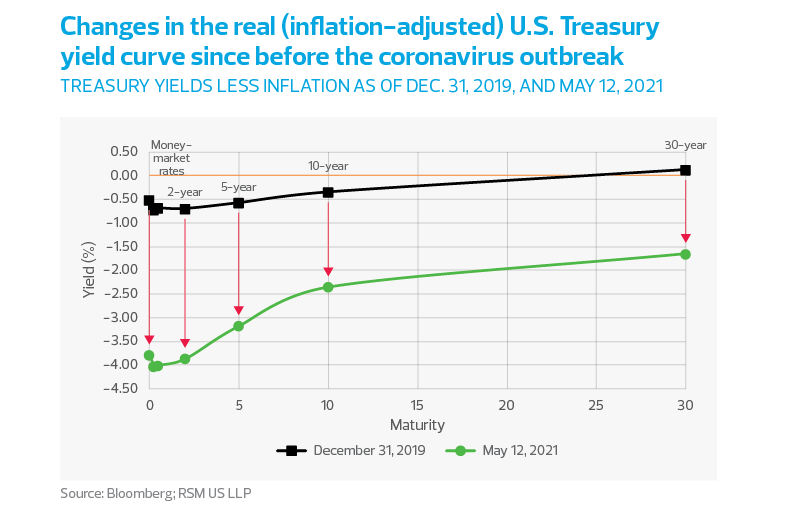

During the decade-long recovery from the Great Recession, U.S. real short-term interest rates have been negative and below the natural rate estimates for all but a few occasions.

That indicates an accommodative monetary policy, even during the period of interest-rate normalization near the end of the recent business cycle that drew so much criticism.

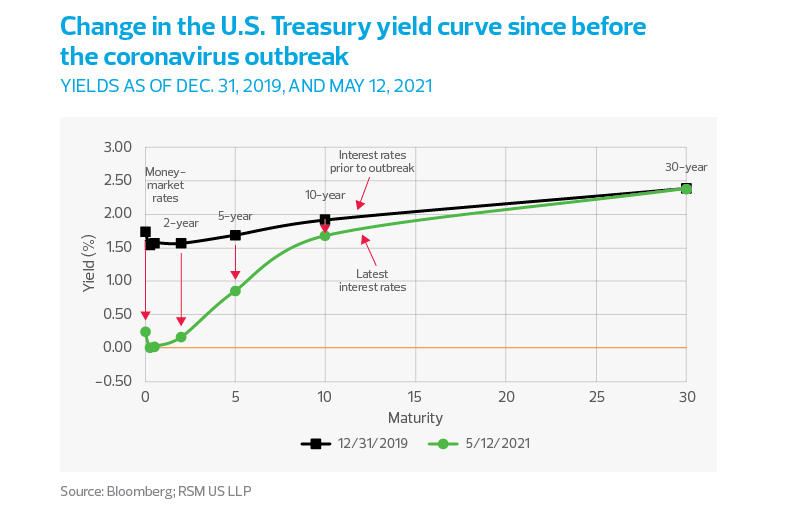

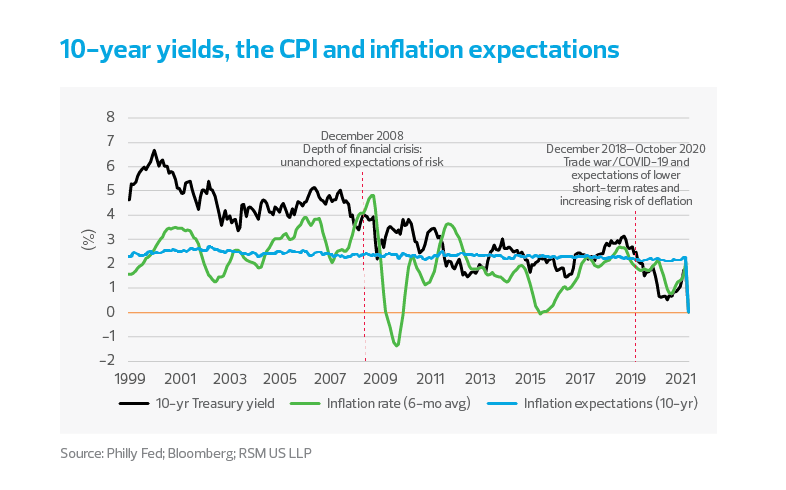

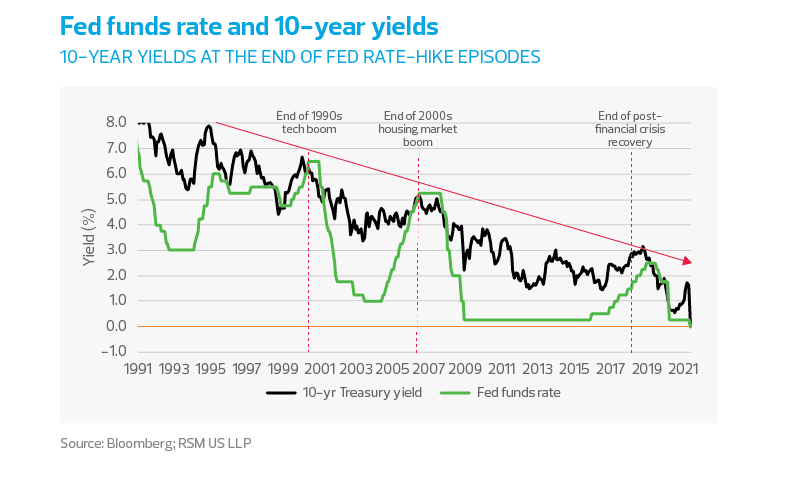

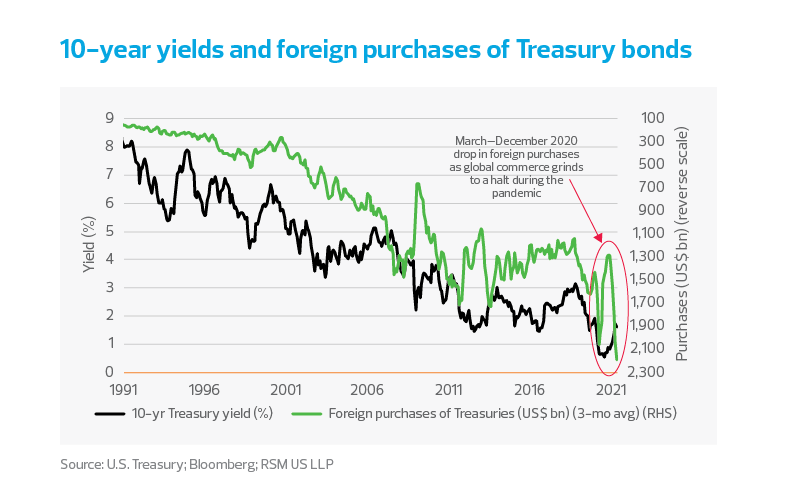

In our opinion, the decline in the natural rate from the Great Recession to the present and the concurrent secular decline in 10-year yields and GDP growth—which we show in the figures below—suggest structural issues in the economy that we have yet to overcome. Despite the best efforts of the monetary authorities, we need to do more to avoid becoming the Japan of this century.

We need to create the foundation for the next economy, both in physical terms—through traditional structural improvements such as rethinking the energy and broadband grids—and in intellectual terms, by addressing the deficiencies in education and health of the labor force.

The United States is no longer the leading exporter of the world. Simply rebuilding the old economy is shortsighted and a waste of resources.

In our estimation, an increase in the natural rate during the first quarter is a positive first step toward the normalization of interest rates, the potential for a sufficient return on investment and the reimagining of the U.S. economy.