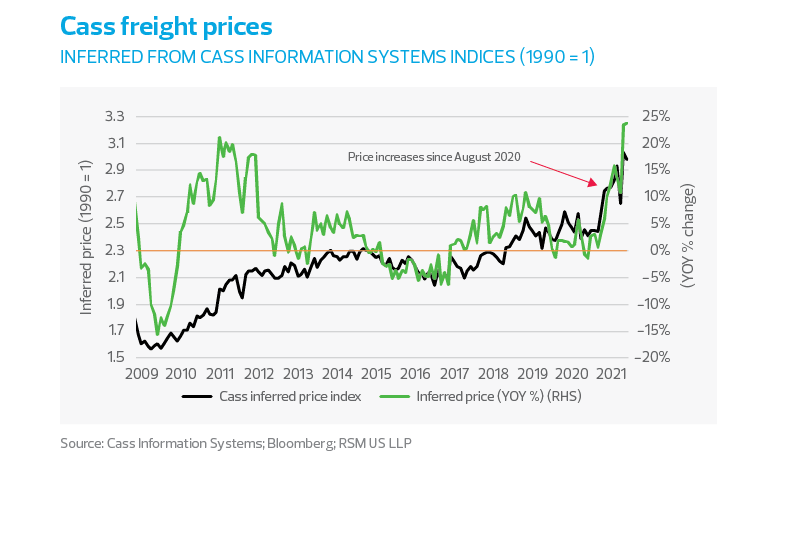

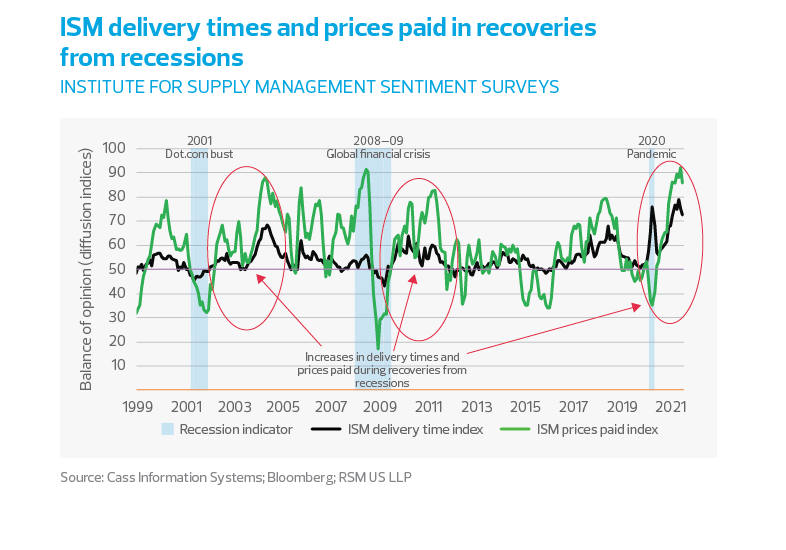

The robust economic expansion that is underway is unfolding in a unique fashion, and it is not for the fainthearted. Everything from semiconductors to employees is in short supply as the economy recovers from the shock of the pandemic and as some workers, especially those in lower-paid service jobs, rethink their place in the labor force.

Now, these bottlenecks are leading to a reconsideration of how quickly the global and domestic economy can move beyond 2019 levels. That reassessment, in our estimation, is the primary factor behind the recent volatility across equity and other financial markets.

The disruptions linked to the delta variant are sufficient to represent risks to our growth forecast of 5% for the global economy and 6.6% for the U.S. economy this year and could lead to further price volatility.

Throughout the global health crisis, we have consistently made the case that for the economy to fully recover, the pandemic must be contained. For this to happen, vaccines must be made globally available.

Until then, consumers will find themselves choosing between higher prices for goods and services and delaying purchases until supplies are back to normal. Each has the potential to dampen overall spending and suppress growth.

It all prompts a question: How did we get here? A closer look at the rising virus cases in Southeast Asia and their effect on supply chains and the labor market can offer some insight.

Southeast Asia

To get a sense of the far-reaching impact of the delta variant on the global supply chain, consider the case of Southeast Asia.

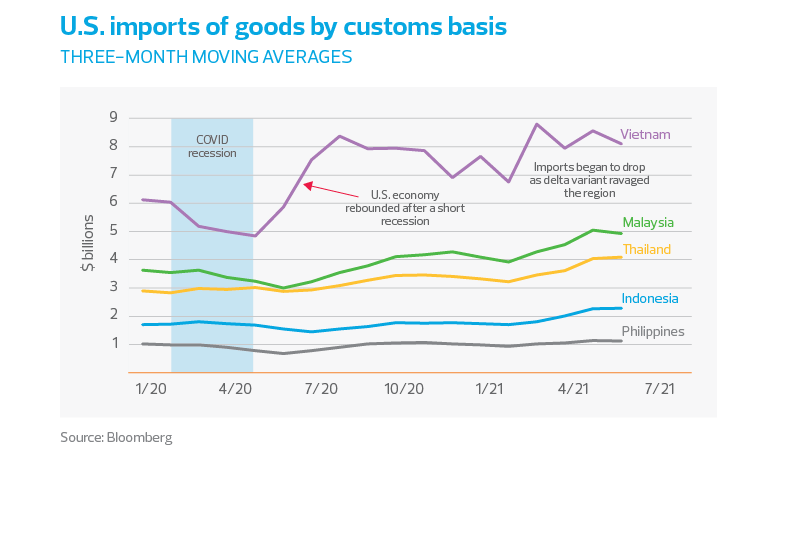

Once viewed as a reliable import portal for the U.S. during the pandemic, Southeast Asia has been hit hard by the resurgence of COVID-19.

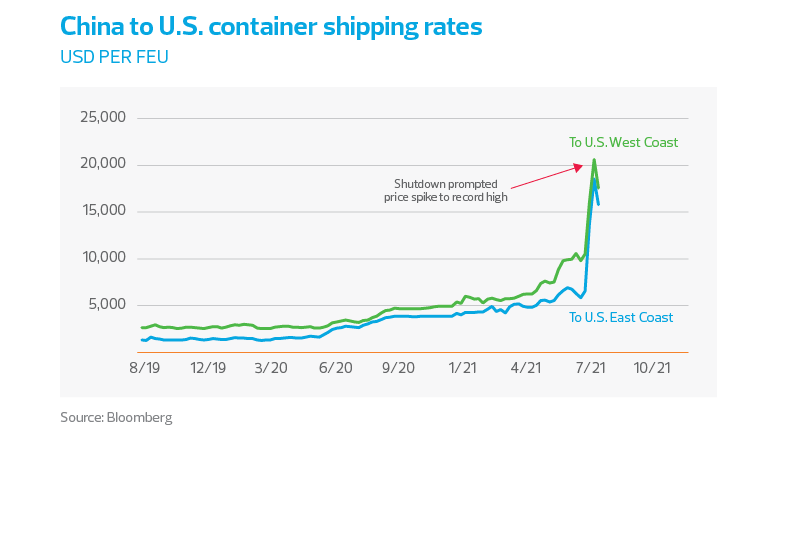

Nations are now in various levels of economic shutdown, leading to drastic cutbacks in production and severe shortages in vital goods sent to the rest of the world.

This is no small matter to the American middle market economy. The U.S. relied on Southeast Asia for about 21% of its food imports, 12% of machinery and appliance imports, and 10% of consumer goods imports in 2019, before the pandemic. In addition, Southeast Asia shares the same trade route with China, Japan and South Korea, which combine for 27% of all U.S. imports.

The disruptions linked to the delta variant are sufficient to represent risks to our growth forecast of 5% for the global economy and 6.6% for the U.S. economy this year.

For this reason, firms with direct and indirect exposure to Southeast Asian supply chains should prepare for further disruptions later this year that are likely to spill over into next year. Middle market firms may need to look to local U.S. and North American producers as possible substitutes to meet increases in demand.

The third quarter in particular has been a challenge as COVID-19 cases continue to rise and prompt economic shutdowns in major countries, including Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia and the Philippines. Local governments, in turn, have swiftly enacted strict stay-at-home policies as hospitals contend with a surge in patients. As a result, U.S. imports of goods from these countries started to show signs of decline in June.