Much has been made throughout the last few years of the need for clubs to run like businesses. The question that emerges is what this declaration actually means in real, operational terms. After all, if clubs have not operated like businesses for the more than one hundred years of the industry, then how have they operated? Like charities?

While board members and commentators call for a more business oriented mindset, the boardroom debates can lead to a tense atmosphere and yet questions about what operating like a business is and whether it is applicable to the club environment are often left unanswered.

Students in business schools worldwide learn early in their education that businesses exist to create, market, deliver and sell widgets (products or services). The mission of a profit driven enterprise is simple: to produce as many or as much as the market demands, at the quantity to satisfy that demand and at the lowest possible cost of production, in the effort to sell at the highest price accepted by the market. Perfecting this process will inevitably lead to profits and a return for the owners, or shareholders, of the business. While many facets make this business model more complex in implementation, the basic tenet is simple. Drive revenue up, drive cost down and put the difference into the pockets of shareholders, perhaps after setting aside some capital to reinvest in order to improve the means of production (i.e. capital maintenance).

Can clubs apply this thought process? Possibly, but they must tread carefully.

Given that most private clubs are non-profit organizations, the economic model is by definition rather different than that aforementioned business model. As with all non-profits, clubs exist because a group of people came together with a mission—to socialize, golf, play tennis, etc. Non-profit, thus club economics begin with the determination of this mission aligned to the wishes of members. Once that mission has been defined, costs can be outlined and a budget built to accomplish this mission. This thought warrants emphasis. Budgets are built from the bottom with costs, not from the top with revenue. Once the cost of achieving the mission (e.g. to have the best golf course, tennis program or dining facility in the area), members need to decide the desired method of financing—dues or user fees. The goal for non-profit clubs cannot be to drive revenue unless the club changes its mission by adding more services or increasing the quality of existing services. Those changes would, in turn, increase costs, which would then require more revenue from the members.

Another method to increase revenue at clubs exists that does not involve changing the amount or quality of services—to increase the number of people willing to pay for those services. This can be the result of an enlarged membership or the opening of the doors to non-members (i.e. a semi-private club). Notwithstanding potential tax, legal and privacy issues around non-member use of the facilities, the primary concern to emerge from the latter modification would be the reaction of current members who will wonder why they joined a private club and paid an initiation fee and monthly dues when a non-member has access to the same amenities. While this is a precarious path for clubs to consider, it is one that has become an economic necessity for many. Concepts, such as yield management, have crept into the club world. Borrowed largely from the hotel and airline industries, yield management addresses filling capacity by setting prices that will attract increased market interest at any given time. A number of clubs have worked this into their golf management philosophy in an attempt to determine the number of rounds courses can handle and what the general public will pay. Companies, such as Boxgroove, have emerged as facilitators in this market space and it has been common practice for management companies at public golf facilities for years. Nonetheless, private clubs must be prepared to respond to the concerns of members when non-members start to appear in the locker room.

As witnessed recently, many for-profit businesses react to a tumultuous financial climate with drastic price reductions intended to attract increasingly scarce disposable income dollars. While many companies will not express much concern when customers who typically shop at low-end outlets are suddenly able to frequent and purchase from high-end retailers, private clubs must consider long-term effects of such occurrences. Clubs have wrestled with the idea of lowering initiation fees, and even dues, in recent years. Desperate to retain dues dollars and members, many resorted to removing financial barriers that were historically a primary mechanism to protect the mission of the club and preserving standards. Lowering admittance standards, and thus provoking members to question whether the club mission is still the one into which they bought, is a very real concern for clubs today. It can certainly seem like a Catch-22 scenario. Decrease entrance barriers (economic or other) to maintain revenue because of the resignation of some long-term members and run the risk of alienating many more members. Maintain standards at a level that requires long-term members to pay more individually to offset the rising cost of exclusivity with a diminishing member base and be prepared for the onslaught of complaints. If ever there was a time for open and honest economic communication with members, now is the time.

Consider the expense side of our private club income statement. Cash optimization is a business practice focused on efficiency (i.e. to obtain the most value possible from every dollar of expense). Many clubs have replaced this concept with simple cost cutting measures—too often without reflection on the mission of the club and desires of the members. The business approach that requires the elimination of unprofitable or inefficient production lines can only be applied in the private club world with much delicacy and after consultation with a club's primary stakeholders, its members. While it may be inefficient to provide service at a poolside food and beverage outlet, no amount of cost accounting analysis will convince members whose kids use the pool every day in the summer that the need for that amenity is anything less than priceless. A club's ability to implement corporate style cost-cutting or 'rightsizing' measures is subservient to the needs and wants of the general membership.

Depreciation is an expense that invites much discussion in private club financial circles. For some, it is an irrelevant non-cash charge. Others routinely preach the mantra of 'funding depreciation' as the foundation upon which to build a good capital reserve policy. Clubs routinely charge depreciation 'below' the line to avoid skewing operating results. Historically, the theory has been that depreciation is in effect 'funded' by initiation fees or similar capital charges. It was not covered by routine sources of operating income. Two items need to be addressed when considering this approach: 1) in the commercial business world, depreciation is an expense, an operating expense; and 2) the inflow of initiation fees from new members has all but disappeared for many clubs. Arguably then, clubs need to consider funding all or some portion of depreciation from operations. Too many clubs appear satisfied with breaking even for the year before depreciation while not noticing that members' equity on the balance sheet has declined from one year to the next because depreciation has exceeded inflows from capital dollars.

When pondering why clubs might fund depreciation, many come to the conclusion that it is to have money in the bank when the time comes to replace or expand facilities. However, this thought process is flawed. Depreciation is the allocation of the historical cost of an asset over the period of its useful life. Inflation guarantees that the typical replacement cost of an asset is significantly greater than its historical cost. Therefore, a club that is building its reserve for future capital needs on the basis of historical cost will have a shortfall when the day actually comes to replace the asset. Best business practices dictate that funding for capital reserves is based on estimated future costs of replacement—not the cost to purchase the asset years earlier. A component of running a club like a business in this context is appropriate capital amenity maintenance, which starts with a professional opinion of needs and timelines. Clubs are advised to consider independent reserve studies by specialists as part of their long range planning.

Meanwhile, capital reserve experts are not the only type of consultant available to clubs. For-profit business long ago adopted the practice of retaining consultants with both positive and negative consequences. (Regarding the latter, the cult classic comedy Office Space should be mandatory viewing for all executives.) Nearly every facet of club operations can be served by a marketplace of experts: marketing and sales, member relationship management, executive recruiting, construction project management, operational effectiveness, strategic communications, strategic planning, board governance. The list of skilled resources upon which club management can call continues—if boards of directors sanction the cost. While every discretionary spending decision has some element of cost-benefit analysis, boards of directors often adopt a rather simplistic approach to what is required to enhance business management competencies at their clubs. Board members may need to be oriented in the intricacies associated with the multi-faceted operation their club represents if they are to be expected to appreciate the benefits of using consultants as often as they do in corporate business dealings.

Increased demands for timely, relevant information to support more rapid decision making have migrated into the private club world. As software companies strive to keep pace with the demand for information, shorter decision cycles should dictate more autonomy for management while being wary of information overload and the subsequent phenomenon known as analysis paralysis. While careful consideration of information is required prior to a significant business decision, clubs are not yet prepared for the extreme manner of data mining associated with such industries as baseball as depicted in the film Moneyball.

Another question that must be addressed in the quest for more rapid decision making is whether club boards and committees are ready to remove themselves from the decision tree. Taken to the extreme, some club commentators are asking whether there is even a place for committees in the modern, professionally operated private club. Consider how the club committee structure compares to the business world. Management by committee led to many problems at corporations, such as General Motors. If attention is turned to another powerhouse of the U.S. economy, General Electric (GE), one can observe a governance structure that calls for a board of 13-17 members and only five standing committees, of which only the audit committee appears to meet on a monthly basis. If members of clubs feel strongly about operating like a business, consider why clubs would maintain the same governance structure as days gone by when they were reportedly not running like a business. Logic would dictate that trust in professional staff is demonstrated through empowerment with legitimate authority from the board. While some board members will inevitably question the financial costs associated with a committee structure, question whether the staff time preparing for and attending monthly committee meetings has ever been subjected to the same level of cost-benefit analysis applied to various areas of operations. At a minimum, the governance structure should be reviewed for relevance and effectiveness as thoroughly as club operating performance.

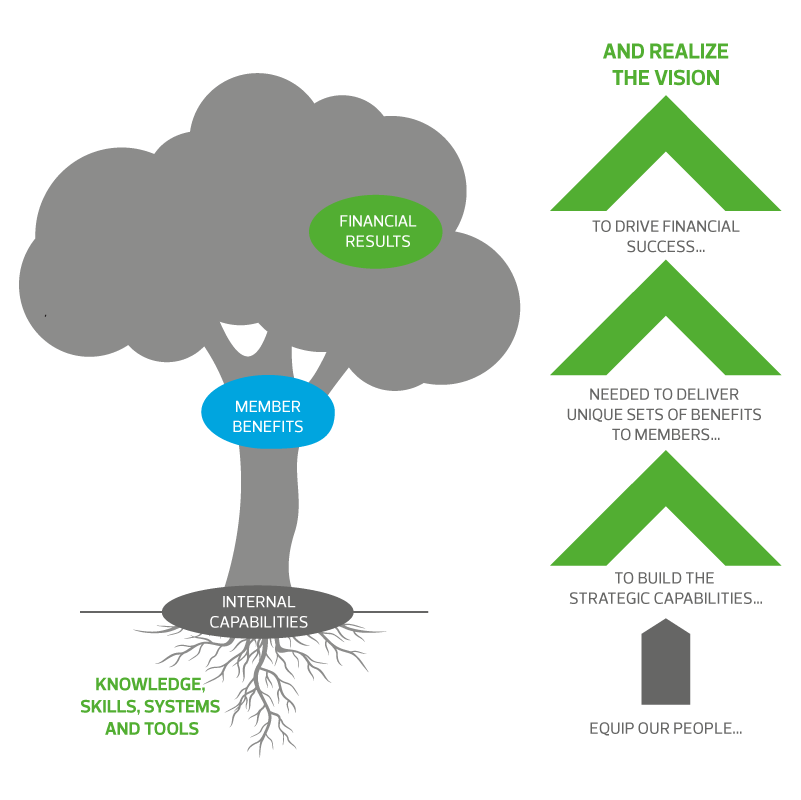

Successful businesses not only need sound strategic planning and formulation, but also sound strategy execution. However, in most organizations, including clubs, a strategic management process is absent. While generally accepted tools are used to manage finances, members, processes and employees, rarely is one applied to the management of strategy. The Balanced Scorecard is an approach that strategically focused organizations can use to fill this void.

The Balanced Scorecard calls for a mix of past, present and future measures. It incorporates a broad range of metrics into an integrated system while ultimately focusing on a few key strategic goals. Organizations, such as Mobil, Wendy's and Hilton Hotels, have instituted a Balanced Scorecard approach and achieved breakthrough results. The scorecard methodology allows these businesses to be strategically focused by placing strategy at the center of the management process to reflect a natural cause and effect logic in business performance.

The Balanced Scorecard looks at performance through four lenses. Each is essential to achieve organizational goals.

- Learning and growth: To achieve our goals, how must we learn, communicate and grow?

- Internal: To satisfy our members, in which business process must we excel?

- Member: To achieve our vision, what member needs must we serve?

- Financial: To satisfy our members and other stakeholder (e.g. lenders), what financial objectives must we accomplish?

Consider the following depiction of how the Balanced Scorecard can help drive performance: