The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (the “TJCA”), enacted in 2017, resulted in significant changes to the treatment of research and experimentation (R&E) expenditures under section 174 of the Internal Revenue Code (“the Code”.) Beginning next year, companies will no longer have the ability to immediately deduct R&E costs when paid or incurred. Instead, such costs must be capitalized and amortized over a 5-year or 15-year period, depending on whether the research was conducted in the U.S. or abroad.

When considered in correlation with President Biden’s proposals to reform the manner in which U.S-based multinational companies are taxed on profits earned overseas, as well as the renewed focus on domestic manufacturing and innovation outlined in the proposed infrastructure bill, the resulting paradox is to encourage onshoring of research to the U.S., while simultaneously removing a key incentive to conduct research domestically. &

Life sciences companies heavily reliant on the current deductibility of research costs will face unique challenges and considerations as a result of the upcoming change, and many companies will also need to reassess their global footprint and supply chains, with a view towards determining the feasibility and overall business justification to support onshoring operations to the United States, or alternatively, maintaining or shifting research activity outside of the United States.

Research drives life sciences

Innovation and resiliency are the two defining characteristics of the life sciences industry that came into focus as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. When faced with a global health crisis that devastated lives and crippled economies, the U.S. life sciences ecosystem was able to adapt, innovate, and quickly pivot to support critical medical device supply chains and develop breakthrough therapies and vaccines to combat the virus.

This was possible because of the research and innovation capabilities of our institutions and the resiliency of our manufacturing and scientific professionals. This effort was not without its challenges and many aspects of the system showed their vulnerabilities in terms of supply chain bottlenecks, decades of offshored manufacturing, and labor shortages for the highly skilled professionals that the life sciences depend upon.

Both the Trump and Biden administrations recognized these challenges not just within life sciences but across much of the U.S. economy, and put efforts in motion to support and rebuild our domestic capabilities for the future. Leveraging the Defense Production Act, issuing executive orders on “Made in America”, and the proposed infrastructure bill currently making its way through Congress, all represent steps towards a more resilient and innovative U.S. economy.

The life sciences industry is the tip of the spear when it comes to innovation, and is exemplified by the startups and middle-market companies that are the life blood of the ecosystem. As illustrated in RSM’s most recent Life Sciences Industry Outlook, record-breaking amounts of private equity and venture capital are flowing to private companies, and those private companies are developing the next generation of therapeutics and medical devices. In the first half of 2021, 45% of all new drug approvals were the first drug to be developed by the sponsor; that is up from 22% in the previous year. This is an incredible feat considering the extremely high failure rate and oft-cited multi-billion dollar cost of bringing a new drug to market.

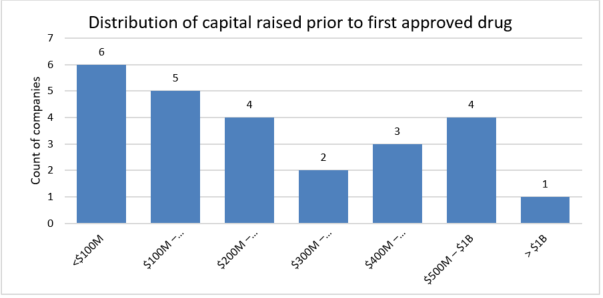

But the industry is changing, and while the traditional thinking is that only large pharmaceutical companies are capable of developing new drugs, middle-market companies become increasingly competitive in this space as they find efficient and effective ways to leverage technology, conduct research, and develop new business models that can do more with less. This is clearly illustrated by the 25 companies that had their first drug approved between 2020 and June 2021. Of those companies, the average amount of financing raised was $330M, and more impressive, was the six companies that were able to do it with less than $100M in financing.

While this analysis does not quantify the cost of failed drugs and companies, it does highlight the need for middle-market companies to manage finances and make every dollar count, especially when research and development efforts have rapid burn rates.

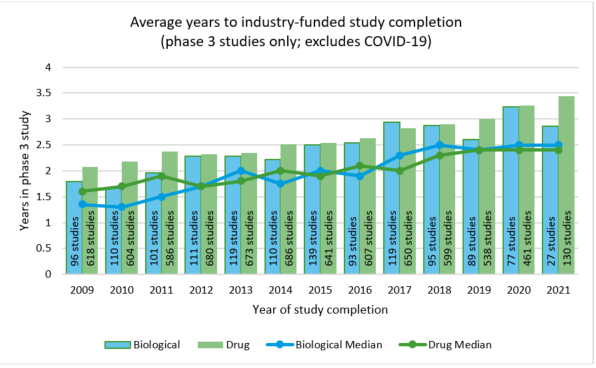

It is also important to remember that life science companies are pursuing more difficult and specific indications, for smaller populations, and complex medtech that blurs the lines between devices and drugs. This is all being done in the pursuit of personalized medicine and a higher quality of care. It also increases the time and effort required in research and development. Over the last decade, the average time to complete a Phase 3 study has increased from 1.5 to 2.5 years.

As the responsibility to research and develop the next generation drugs and therapies falls to middle-market companies, it is important that they have access to capital, accommodative policy support, and a business purpose to pursue these efforts, domestically.

Deducting research and experimental expenditures under section 174 of the Internal Revenue Code

Since 1954, life sciences companies have been able to currently deduct qualifying R&E expenditures under section 174 in the year they were paid or incurred. Alternatively, such costs may be capitalized and amortized over a period of no less than 60 months, commencing when the taxpayer first begins to derive benefit from the expenditures, or they may be indefinitely capitalized. Software development costs may also be currently deducted under the authority of Rev. Proc. 2000-50, due to the similarity of those expenditures with those that qualify as section 174 costs.

The underlying rationale behind the enactment of section 174 was two-fold: (i) the elimination of uncertainty as to the tax treatment of research expenditures by giving companies the choice of expensing or amortizing such costs; and (ii) to provide companies with a tax incentive to make investments in R&D.1

Beginning in tax years after December 31, 2021, TCJA removes these options and requires capitalization and amortization of items classified under section 174 over either a 5-year period for domestic expenditures or a 15-year period for foreign-incurred expenditures, beginning at the midpoint of the tax year in which the expenditures are paid or incurred. In addition, through a modification to the statute, amounts paid for software development would be specifically treated as section 174 expenditures, thus subjecting them to similar capitalization/amortization treatment.

As a further whipsaw, capitalized R&E must continue to be amortized over the remaining applicable recovery period even if a research project is abandoned, disposed of, or retired.

While these new rules do not prevent life sciences companies from taking a deduction for R&E, nor impact the ability of a taxpayer to claim the R&D tax credit under section 41, they very much impact the timing of when such companies are allowed to take that deduction which, in turn, could impact broader tax planning strategies around R&D or erode cash necessary to run the business.2

Prospects for legislative change

The upcoming change to section 174 has caught the attention of certain members of Congress, including Senate Finance Committee Chairman Wyden, as well as both Democrats and Republicans in the Senate and the House. To this end, various bills to repeal the scheduled switch to amortization have been introduced over the years. The most current bills pending in Congress are S. 749 (the “American Innovation and Jobs Act”), introduced in the Senate on March 15th, and H.R. 1304 (the “American Innovation and R&D Competitiveness Act of 2021”), introduced in the House on February 24th. More recently, the Senate adopted a non-binding amendment, as part of its consideration of the fiscal year 2022 budget resolution, to preserve full expensing under section 174.

Earlier this year, President Biden, as part of his Build Back Better tax agenda, announced various proposals that would expand support for domestic manufacturing and innovation. The president’s proposals would make significant investments in R&D spending, ranging from funding for the acceleration of drug development and pandemic preparedness, research infrastructure upgrades, regional innovation hubs, and small business innovation.

As a means to offset the cost for these (and other) investments, the president also proposed a series of tax changes that would impact corporations and wealthy taxpayers, including an overhaul of the Code’s international business tax provisions and the taxation of foreign profits, with a goal to prevent the offshoring of jobs and factories, while increasing incentives to onshore research and manufacturing activities. At the same time, proposals from Biden and Sen. Wyden seek to eliminate or modify an existing tax benefit that allows a deduction for foreign income derived from certain U.S.-held assets (i.e., the foreign-derived intangible income regime, or “FDII”). The president would repeal FDII and use the resulting revenue to support other domestic research incentives (which are not further defined), while Sen. Wyden would modify the manner in which the benefit is calculated, giving more prominence to U.S. based innovation income, and would also include worker-training expenses in the calculation.

Impact to Life sciences companies

Life Sciences companies that choose to maintain, enhance, or onshore research activities to the U.S. will face a host of considerations. Established entities, still recovering from supply chain disruptions and restructuring brought on by the pandemic, would encounter workforce challenges such as training and re-skilling of specialized employees, liquidity concerns, and ensuring compliance with regulations, among other things. Mid-size companies would need to ensure that platforms to growth remain unhindered, and smaller start-ups and biotech companies, dependent on strategic alliances and collaboration with others, would need to carefully review these arrangements and adjust to new and changing dynamics. For all companies, an evaluation of where research activities are currently undertaken, an assessment of the overall tax benefits, and the feasibility of relocation must all be considered.

In addition, as drugs and devices increase in complexity and target rare and difficult indications, the likelihood of abandonment of a project is increasing. The new law requiring the continuation of cost recovery in such cases will be a fundamental change to the basis recovery rules. There is also data suggesting that the average length of time from Phase III to commercialization has been increasing over the last decade, which is leading to more rounds of financing and a longer path to profitability which, in turn, will generate additional expenses.

Life Sciences companies that are reliant on software (e.g., to drive virtual trials) would also need to evaluate and model the different scenarios as to where development activities should take place from a geographical perspective, access to data considerations, and operational considerations as to where servers should be located or programmers should reside.

Lastly, Life sciences companies will need to determine whether the U.S. provides an environment that will foster innovation and growth to further justify relocation. Existing federal incentives such as the R&D tax credit and the orphan drug credit (where applicable), as well as incentives provided at the state and local level, should be measured against the potential benefit afforded under various countries’ patent box and other incentive-oriented regimes.

Companies could view foreign markets, which continue to implement favorable tax policies for research conducted within its borders, as locations that are more conducive for undertaking significant research activity, a result which directly undercuts the overarching message of President Biden’s Build Back Better agenda, and the need to further enhance the global competitiveness of the U.S. in this area.

Action Path forward

All industries and sectors involved in research, development, and innovation need to monitor the scheduled expiration of R&D deduction provisions under section 174. The inability to immediately deduct qualified research costs would impact liquidity, reduce after-tax cash flows, and serve as a disincentive to pursue domestic R&D and innovation efforts. The life sciences industry, which relies almost exclusively on its ability to innovate and develop new and more effective products, will be acutely impacted as it has to decide where and how to conduct future research that can take years to complete and is incredibly capital intensive. Companies need to understand the different scenarios and tax results that may result once the changes to section 174 take effect.

Source: Evaluate Ltd., RSM US

Source: National Institutes of Health, RSM US

1 See generally, “Section 174 and Investment in Research and Development,” Guenther, Congressional Research Service Insight, August 10, 2020.

2 Section 174 has a symbiotic relationship with the section 41 research and development (“R&D”) tax credit. As part of the R&D tax credit eligibility determination, a four-part test for qualified research expenses must be satisfied. For purposes of determining whether an expense was incurred with respect to qualified research, one requirement is that such expense “may be treated as” an expense under section 174. The TCJA conforms section 41 with the amendments made to section 174.