The 5-over-1 has come to define the increasing homogeneity of America’s multifamily properties.

Key takeaways

Building codes, zoning trends and consolidation are factors contributing to the rising uniformity.

The risks of standardization include repeating past mistakes that still plague suburban America.

If you walk into any McDonald’s across the United States and order a Big Mac, in short order you will be served a sandwich made of two all-beef patties, special sauce, lettuce, cheese, pickles, onions on a sesame seed bun. As a consumer, you may value the efficiency and consistency of this homogenous experience, which goes beyond the meal to include design. Enter a random McDonald’s to use the restroom facilities and you’ll know where to look: toward the back of the restaurant, near the side entrance.

In commercial real estate, it is not just restaurant chains using standardized building templates but also hotels, gas stations and big-box retailers. Picture the nearest supercenter and you can probably envision where to find the cash registers and all the major sections (e.g., electronics in the back center, pharmacy at the front, grocery on one side). That’s because chain establishments typically repeat the same exterior design and interior layout for every location.

Now the same uniformity has been extended to multifamily properties.

How luxury in a box became the new American dream

The 5-over-1 has come to define the increasing homogeneity of America’s multifamily residential buildings. This style comprises four or five floors constructed of Type III or Type V combustible materials (typically wood) over one floor of a fire-resistive Type 1 podium (generally concrete), as defined within International Building Code section 510.2. The ground-level concrete podium is commonly used for retail or residential amenity space, and the floors above it are for multifamily living quarters, often billed as “luxury” condos or rentals. These buildings are popping up all over the country in new developments and are typically big and blocky, pushing up to the very edge of the sidewalks.

Most municipalities within the United States have jurisdiction to determine which building codes to adopt and enforce. Yet, most of these codes do not differ because the cities lack the time or resources to write their own comprehensive building codes, resulting in blanket adoption of the IBC.

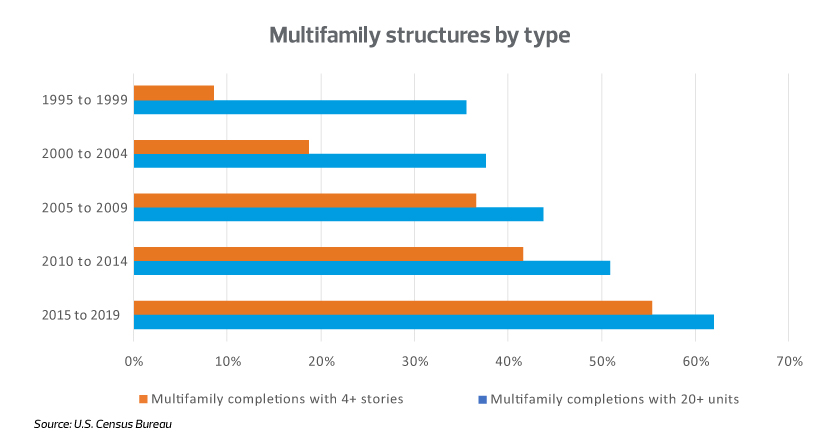

Prior to the 5-over-1, which entered the market during the mid-1990s, multifamily housing typically fell into one of two classes: smaller single-family house replicas or massive steel and concrete high-rise structures. The introduction of the 5-over-1 was driven mainly by a change of wording in the IBC, classifying exterior and interior walls built with flame retardant-treated wood as noncombustible.

Building viable solutions amid challenging circumstances

Beyond the building code, what has truly helped spur the creation of these buildings has been America’s zoning practices, established to reserve approximately 75% of all residential zoning for single-family use. With America in desperate need of additional housing and so much zoning ceded to single-family homes, just a tiny segment is left for high-density development. Property developers are forced to squeeze in as many units onto plots as possible, often competing with retail and office developers for properties located just off highway exits or on the fringe of downtown.

Furthermore, the real estate development industry has experienced consolidation in deal-making. Of the 530,000 starts in multifamily housing (any housing project with greater than two units) in 2020, 17% were with the 25 largest developers, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau and National Multifamily Housing Council. The consolidation has helped them create scalability in their builds.

But to start, the limited availability of land drives up its price, meaning that a smaller tranche of developers can afford to purchase it, and an even smaller number can ultimately turn a profit.

On a per-unit basis, 5-over-1s are often cheaper to build than other types of buildings, as wood is far less expensive than other materials. Wood is also easier to work with, limiting the need for skilled labor. A lower per-unit cost allows 5-over-1 developers to outcompete smaller developers within the market, leading to even greater consolidation of developers and expansion across multiple states.

As a practical solution to the housing crisis, it can be argued that 5-over-1 properties are what America needs. These large developments establish reasonably priced, high-density housing units in or around urban cores for Americans to live in—so, what are the potential downsides?

Not letting past mistakes shape the future

Despite the positives, a major concern about standardization has emerged—whether if left unchecked it risks repeating the strip mall dilemma that has plagued much of suburban America. In the 1950s, when automobile ownership increased and demand for car-friendly retail skyrocketed, strips of retail with ample parking began popping up across the country at a record pace. They had few design elements other than the tenant signage lining the concrete storefronts, because developers were focused on getting them built and leased as quickly as possible.

Fifty years later, the Great Recession forced many retailers and small businesses occupying these spaces to shut down. Meanwhile, the proliferation of online shopping has transformed consumer preference in favor of walkable retail in new urbanized communities, resulting in vacant, abandoned strip malls that have remained eyesores generating little to no value to their owners or communities.

With the needs and wants of Americans constantly evolving, will the 5-over-1 properties lining the streets of new, in-demand communities maintain longstanding appeal or become the next eyesores sooner than investors expect?

It depends, as there are clear benefits and risks to standardization. Building with consistent floor plans and common materials should help reduce product waste and optimize supply chains, which is increasingly important as sustainability concerns increase. Additionally, standardization should help increase product sales with buyers and renters at a time of growing need, given the year-over-year price of shelter has climbed by 6.6%, according to September’s consumer price index data. The trade-off, though, is a lack of uniqueness and, perhaps, aesthetic appeal, making it less likely to stand the test of time.

However, all these factors spell opportunity for real estate developers. Middle market developers looking for greater scalability can leverage standardization to streamline operations, while those looking to appeal to a niche market can create a competitive advantage by building something unique.