The rise of the P3 model

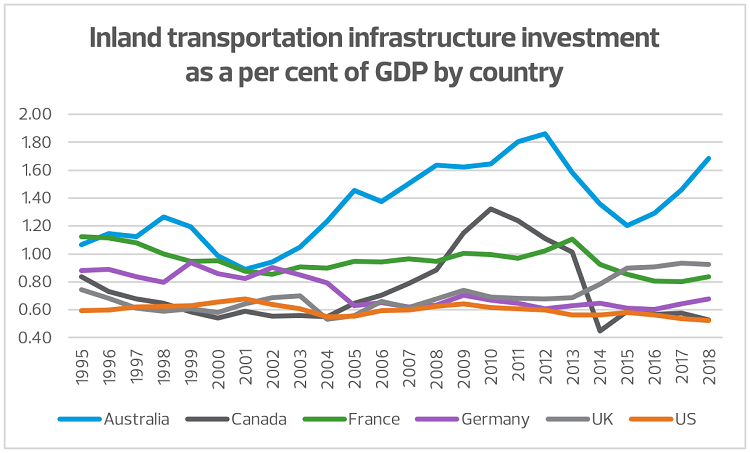

Countries like Australia, the U.K. and Canada, which invest a larger proportion of their GDP in infrastructure, have one important thing in common. Since the 1990s, they have very much embraced alternative delivery mechanisms like P3s to develop infrastructure projects. The United States has not; instead, it has utilized its deep municipal bond market to finance many large-scale infrastructure projects.

P3s, however, are different; and while the issuance of municipal bonds imposes some discipline on project sponsors, they do not transfer risk to proponents in the same way alternative delivery mechanisms like P3s do. Theoretically, transferring risk to project proponents has the potential to lower the risk-adjusted cost of developing an infrastructure project. Risk-adjusted being the key word. Organizations like Infrastructure Ontario and other government agencies that regulate and sanction P3s have developed processes and procedures to assess the extent of risk transfer through value for money analysis.

P3s can be structured in a variety of ways depending on the scale and extent of private sector involvement. Theoretically, increased private sector involvement leads to increased risk transfer (i.e., private sector taking more risk for the design, construction and maintenance of the infrastructure asset). Presumably, increased risk transfer would generate more value for the money for taxpayers. In practice, however, the performance of P3s to generate value for money is mixed.

Proponents of P3s point to countries like Canada that have generally embraced P3s and where private sector contributions to public infrastructure projects have expanded significantly. However, an analysis conducted by Ontario’s auditor general found that 74 projects completed via P3s cost taxpayers $8 billion more than expected over nine years. Organizations like Infrastructure Ontario retort that spending $8 billion more than expected is a small price to pay to have infrastructure in place and that had the public sector completed those projects, it would have cost the taxpayer $16 billion more. And herein lies the big issue with P3s: It is very difficult to assess their effectiveness. We do not know with absolute certainty what would have happened in their absence.

Unfortunately, it is almost impossible at the outset of any large-scale infrastructure project to know its final cost. For instance, the project can be delayed for a number of reasons, and every day of delay imposes additional costs. The project can also run into a number of engineering, design and construction challenges that require additional work to be conducted beyond the original budget estimate; and for some projects, the time and investment required to obtain permits can far exceed the original estimate. Increasingly, issues related to a project’s social license are creating substantial challenges for project proponents and necessitating significant effort in addressing the concerns of local communities. Indeed, social issues are now the main cause of infrastructure projects cost overruns and delays, and those risks are very hard to transfer to the private sector.

In countries like the United States, P3s are not yet as common, and we may expect to see a rise in their application. However, engineering companies in Canada are now also exploring alternative models that help address the drawbacks from P3s described above.

Evolving P3s to the alliance model

Alliance models, also known as alliance contracting, deliver infrastructure projects using a collaborative approach between the public sector and the private sector parties. Both parties share risks and responsibilities and make unanimous principle-based decisions on key project issues while achieving improved project solutions. As explained by research published by the American Society of Civil Engineers in 2016, alliance contracting is quite effective for large scale, complex and multistakeholder projects and in many respects is more reflective of a true public-private partnership than how P3s are currently practiced. Also, we are now beginning to see the next iteration of alliance models under the Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) models, which use further defined processes and technology to streamline the delivery under these team-based models.

In essence, alliance contracting involves the establishment of a joint public-private sector project team. Collaboration is the essence of alliance contracting where the public and private sector work together to address projects’ risks and are incentivized to do so. This is vastly different from a typical design-build-finance-operate-maintain P3, which is probably better characterized as adversarial. Alliance contracting recognizes that not all project risks can be quantified and transferred, and it warrants serious consideration for complex projects.

Next steps to position engineering firms for success

Ultimately, the choice of a traditional delivery mechanism versus an alternative one depends on the project. Project owners have a number of approaches that can be utilized to incorporate private sector innovation into their project. As key members of a consortium developing an infrastructure project, engineering companies have a critical role to play in working with project owners (often government organizations) to assess the applicability of alternative delivery mechanisms. The benefits of alternative delivery mechanisms like P3s, alliance contracting or IPDs can be significant and help reduce overall project risk and get infrastructure in place quicker. Construction and engineering firms often have an adversarial relationship with project owners, and a more collaborative approach to the development of infrastructure may be warranted.

As Canada and the United States have signaled support for increased infrastructure spending, it is important for engineering firms to ensure they are properly positioned for the resulting projects. Utilizing alternative delivery mechanisms like P3s, alliance contracting or IPDs could be an important aspect to these infrastructure programs as governments attempt to look for ways to add value for taxpayers. Specifically, engineering firms should consider the following:

- Understand the risks related to these alternative delivery models and adjust processes, corporate structures and contract negotiations to manage these risks

- Ensure that internal processes and technology are sufficient to navigate and collaborate under an alternative delivery model, especially under IPD models where solutions like building information modeling (BIM) may be used to streamline collaboration between the project teams

- Foster strong industry relationships, understanding value propositions of potential team members in order to facilitate a smooth transition to any team-based delivery model

- Ensure internal teams are sufficiently trained in order to deliver the most value to the greater delivery team