The potential of reshoring manufacturing jobs and operations to the United States has long been a topic of conversation in the industry and among politicians, but such conversations have for years been largely theoretical. The pandemic has boosted the visibility and potential benefits of reshoring by exposing supply chain fragilities, and the Biden administration has put a spotlight on this issue. But for most companies, the prospect of actually moving operations back to the United States is still laden with complex considerations and nuances.

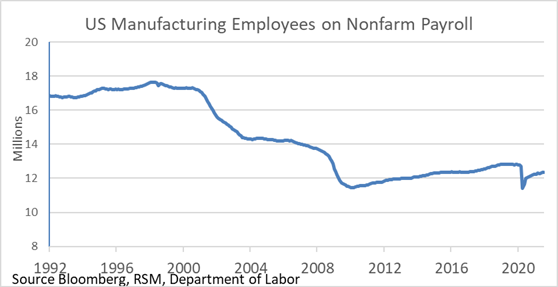

For starters, many of the factors that led to the offshoring of U.S. jobs and operations in the first place are still at play, such as other countries’ lower labor costs, investment incentives and more lax regulations. China, the greatest beneficiary of U.S. offshoring, saw its GDP surge from 6% of U.S. GDP in 1991 to 70% by the end of 2020. Although GDP doesn’t correlate directly with offshoring or reshoring, the indicator sheds some light on just how much growth China has experienced over the same time frame that U.S. manufacturing jobs dropped.

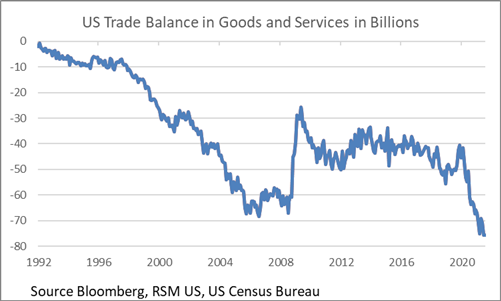

The pandemic has exacerbated what was already a long-term U.S. trade deficit. From 1992 to 2020, the United States averaged an annual trade deficit of $36 billion. So far in 2021, however, the deficit has grown as high as $75 billion. Historically, economic downturns and recessions tend to narrow trade deficits due to reduced spending, as seen in 2009. But the current deficit was driven further by U.S. government spending on stimulus payments to Americans.