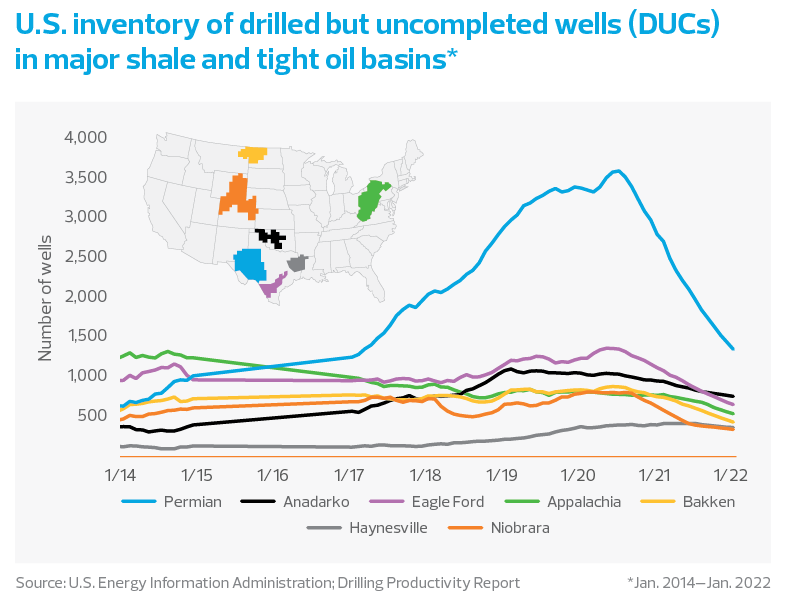

Even though the steep drop in the number of DUCs corresponds with the COVID-19 pandemic, this trend has deeper origins. Before the start of the pandemic, U.S. producers had begun reducing investment in new projects and started exerting more capital discipline.

In other words, as the initial frenzy of the shale boom wore off and the industry began to mature during the 2010s, producers came to the consensus that the shift toward “Shale 3.0” would place emphasis on returning cash to investors over rampant production growth.

Investors, frustrated by years of low returns from the sector, had punished companies that looked to grow production at the expense of shareholder return and rewarded those that did not pursue liberal outlays on capital-intensive new projects.

While overall production and development increased throughout the decade, the development of new wells was more or less stagnant in every major shale basin except the Permian.

The COVID-19 effect

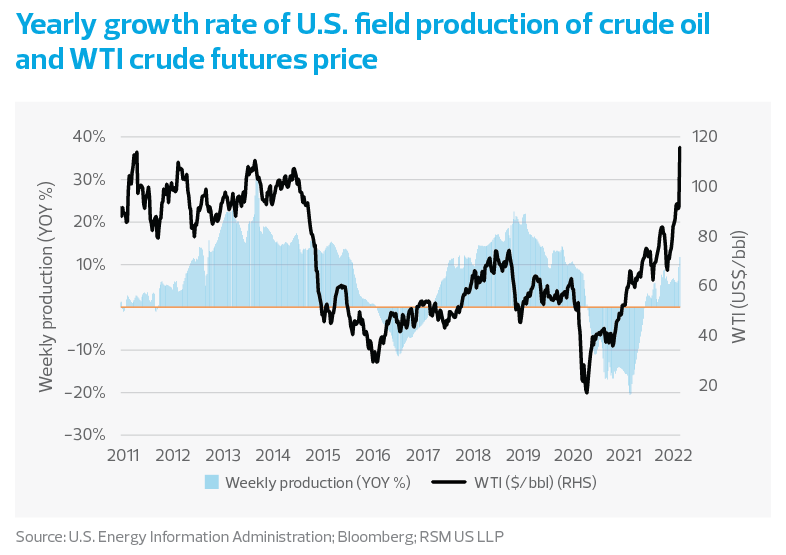

The onset of COVID-19 saw demand for oil plunge, putting prices into a freefall, and forcing domestic producers to close some of their active wells. In addition, many participants inside and outside the industry believed the pandemic was the catalyst for a Green Revolution, and producers began to curtail the scope and number of new projects.

When the economy emerged from the worst of the pandemic, producers responded to rebounding demand by tapping DUCs without drilling new wells to replace the latent capacity. This move was understandable for an industry that was supposed to act more judiciously with its capital, in a world that was supposed to move away from oil.

Now that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has shifted the paradigm again, U.S. producers are significantly behind the curve, and the degree to which they can resume production is constrained by the fact that they have already expended their backlog of DUCs.

Regulatory limits

There are other factors at play. Producers claim that limits on fracking by certain states and the closing of certain coastlines (e.g., Alaska and California to offshore drilling) have also impeded their ability to drill new wells. The impact of President Biden’s attempts to suspend federal auctions for drilling is unclear, although it has become a hotly contested issue in Washington.

In addition, the oil industry is not immune to the effects of the national labor shortage either. The oil industry relies on engineers who are in short supply, truckers who deliver goods and equipment from site to site, and contractors who face worker shortages of their own.

What is certain is that even if domestic producers develop new wells in record time—something that seems unlikely—the United States still, fundamentally, will not be able to drill itself out of this shortage.

The structural exclusion of Russia, the world’s third-largest oil producer, from global markets was always going to hurt. It will certainly hurt Europe more than the United States, as Russian crude oil comprises a negligible 1% to 2% of U.S. imports.

But oil is a fungible commodity for which Russia accounts for 14% of global supply. The amount excluded from the larger market is simply too large for producers in the United States and elsewhere to make up in a short period. In fact, the sanctions’ effectiveness is necessarily linked to price increases in the West. If there are none, then the sanctions cannot have worked.

The takeaway

Yet it is precisely for this reason that the United States and its allies will have to take diversifying their energy streams seriously in the decade to come if they wish to maintain real global influence in the long run.