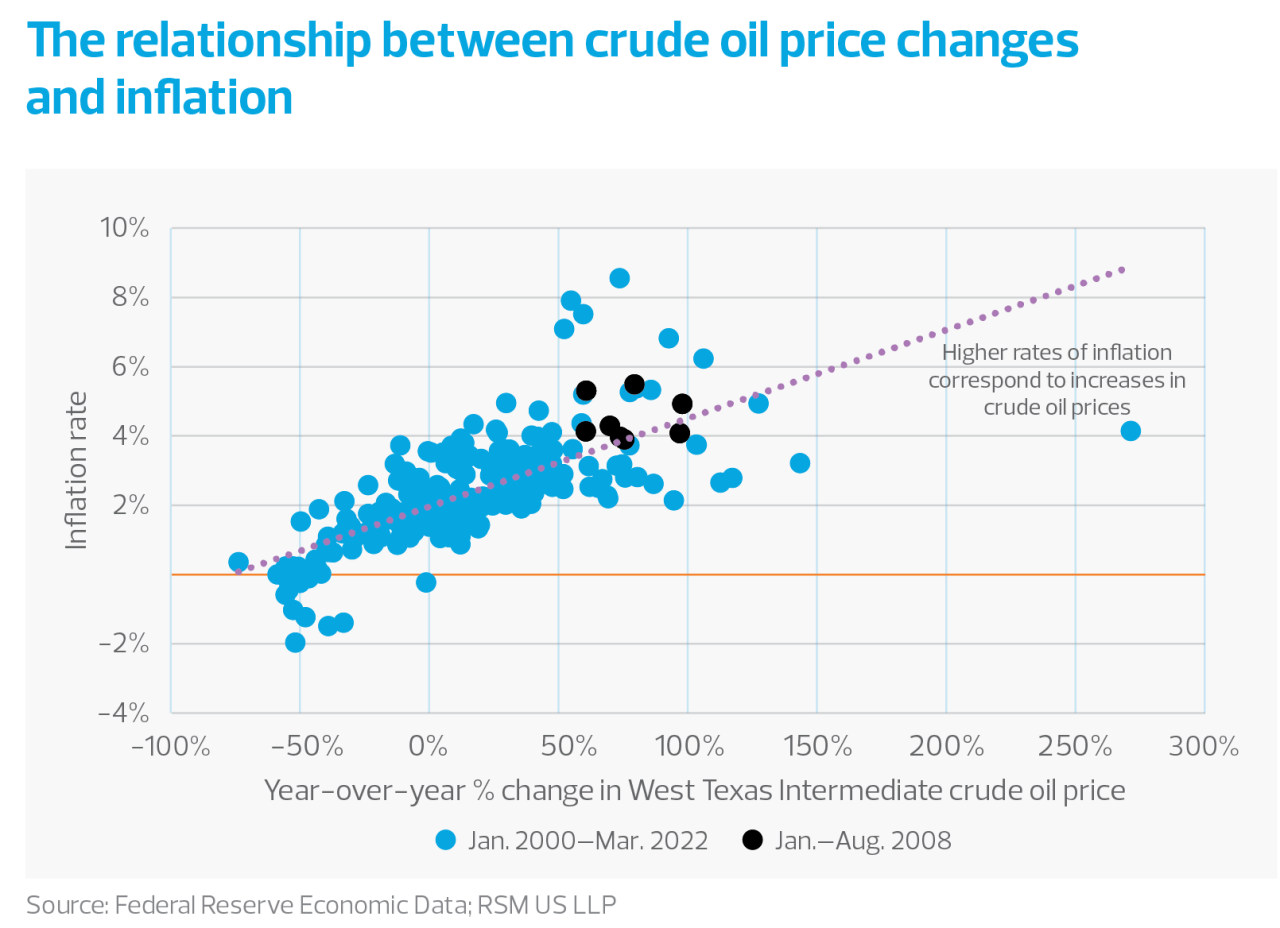

While we expect the annual inflation rate to peak this quarter as the comparisons to the lower levels of a year ago wear off, the risk of rising prices will remain as the twin shocks of the Russia-Ukraine war and China’s coronavirus shutdowns endure.

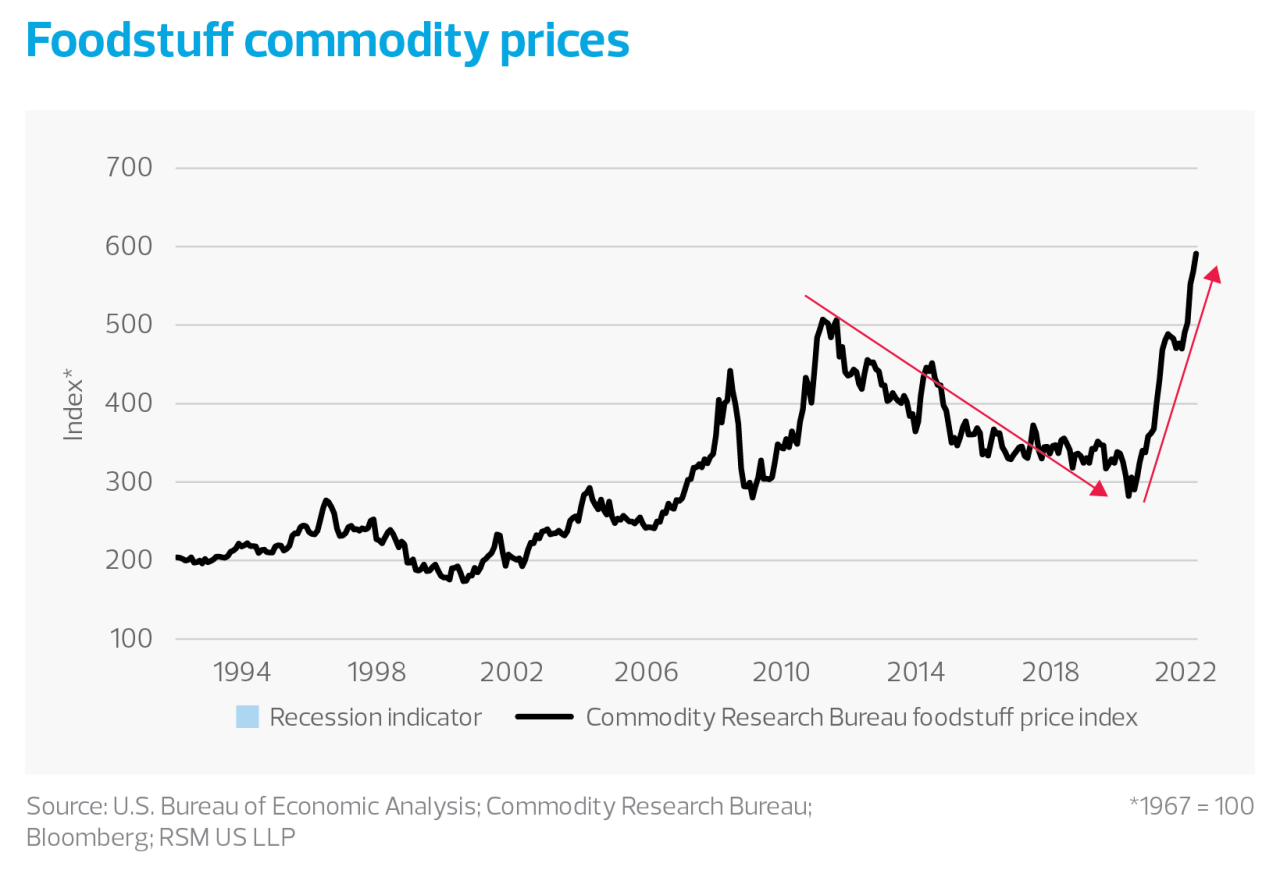

These price shocks will have the biggest effect on lower-income households, reducing their ability to pay for the living essentials, whether it’s driving to work, heating and cooling a home, or putting food on the table.

But the price shocks will also lead to reduced discretionary spending, which will, in turn, cause a slowdown in economic growth that will affect all income classes and businesses.

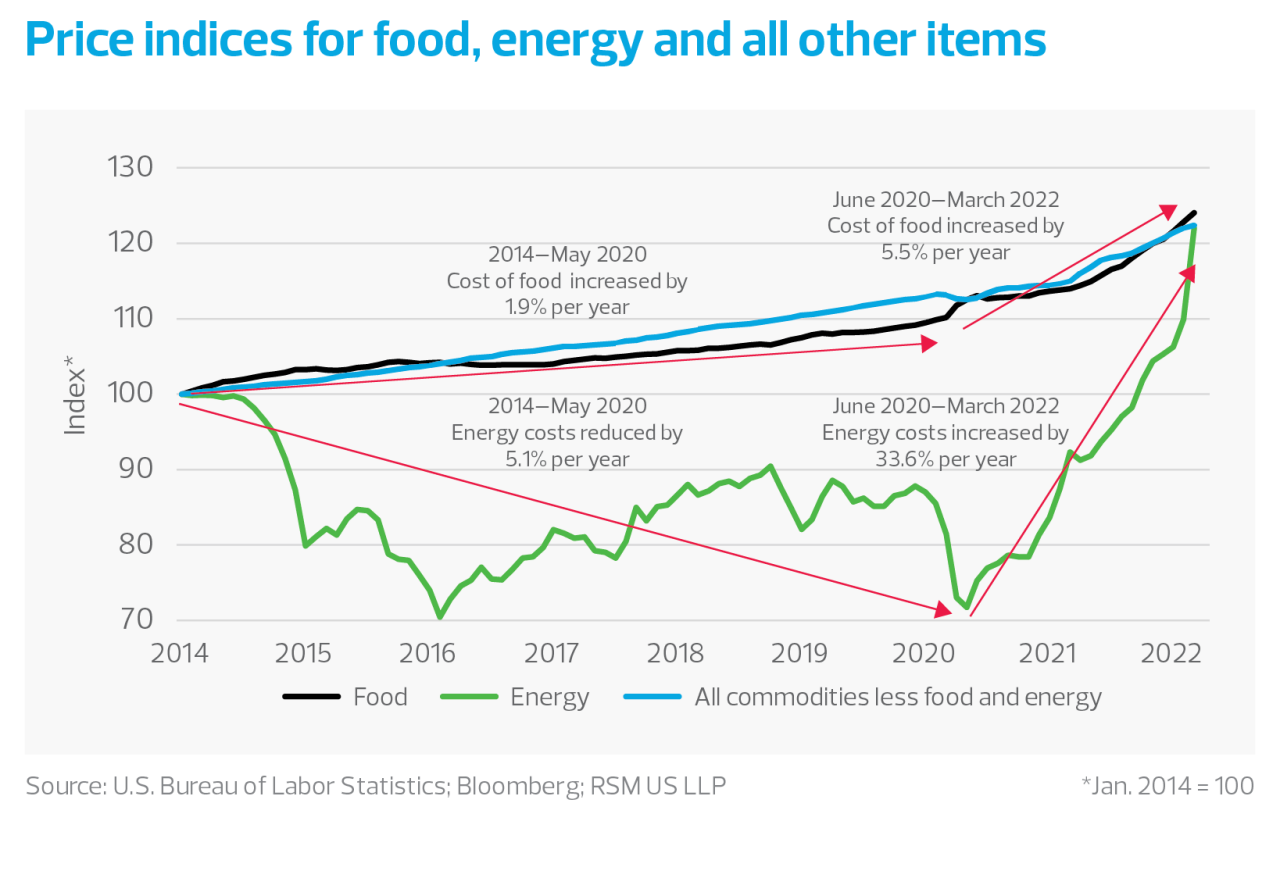

Already, the impact has been significant. In March, food prices increased by 1% over February, and energy prices increased by 11%. The so-called core inflation rate, the items excluding food and energy, increased by 0.3% as rents increased by 0.5%.

The overall consumer price index increased by 1.24% for the month, which over 12 months would amount to an inflation rate of around 15%.

Although we do not anticipate that pace will continue, one has to note the risks around the outlook linked to idiosyncratic factors beyond the control of policymakers and not linked to domestic economic fundamentals.

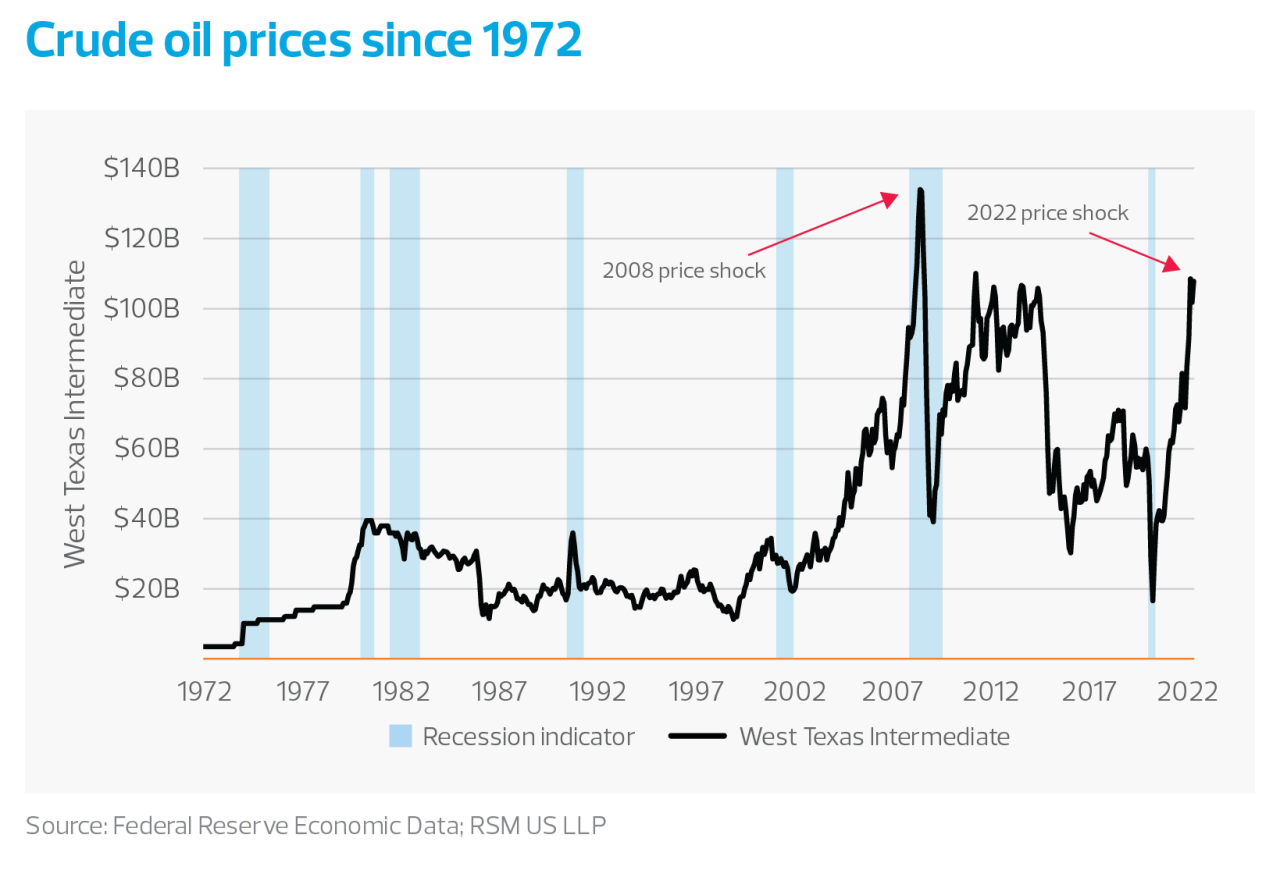

With the European Union's partial ban on Russian oil, we could very well see another test of highs in oil, gasoline and energy prices.

Such price increases would upset the evolving consensus that inflation has peaked and could set the stage for a premature end of the business cycle.

The Federal Reserve can do little about the war or the pandemic in China. So its task is to tamp down embedded inflation expectations, which, if they increase, would most likely lead to hoarding—as we saw in the early months of the pandemic—and a dramatic tightening of monetary and financial conditions.

As in the 1980s, an increase in interest rates to levels needed to end 15% inflation would cause a severe drop in demand and a deep recession, sending millions out of work and defeating the Fed’s mandate for full and equitable employment.

Is a recession inevitable? Can the Fed engineer a soft landing for the economy and bring about price stability?

We think the underlying economy is strong, with businesses taking steps to navigate around supply chain roadblocks and improve productivity. In addition, we expect infrastructure spending to kick in at the end of the year despite further political roadblocks.

Finally, we think that the monetary authorities have the flexibility to adapt to rapidly changing conditions, whether in the rate of economic growth or the rate of inflation. There have certainly been enough disturbances and shocks over the past five years to believe that.

So we remain optimistic, but with our eyes wide-open to the risks.

How did inflation surge so quickly?

Before the war in Ukraine, the focus regarding inflation had been on select items in short supply—as a result of supply chain issues—and the increase in housing costs that account for nearly a third of the overall cost of living.

Many of the increases in product costs were expected to be transitory—as, for example, the skyrocketing cost of used cars that is now decelerating. And with the recovery taking shape, expectations were for the Fed to gradually raise interest rates, which would cool an overheating housing market. At the same time, the end of pandemic income assistance programs and the reduction in savings would moderate consumer demand.

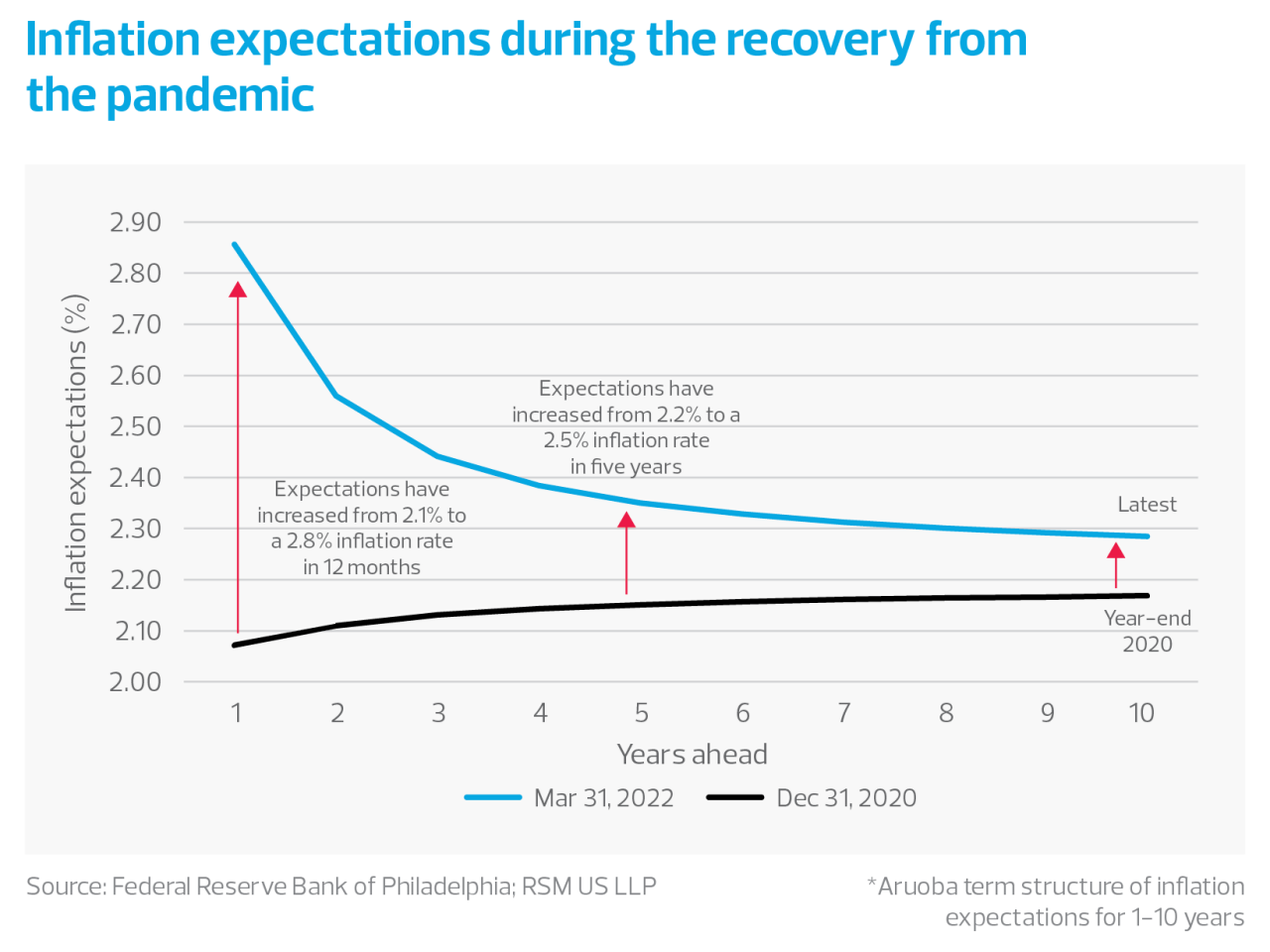

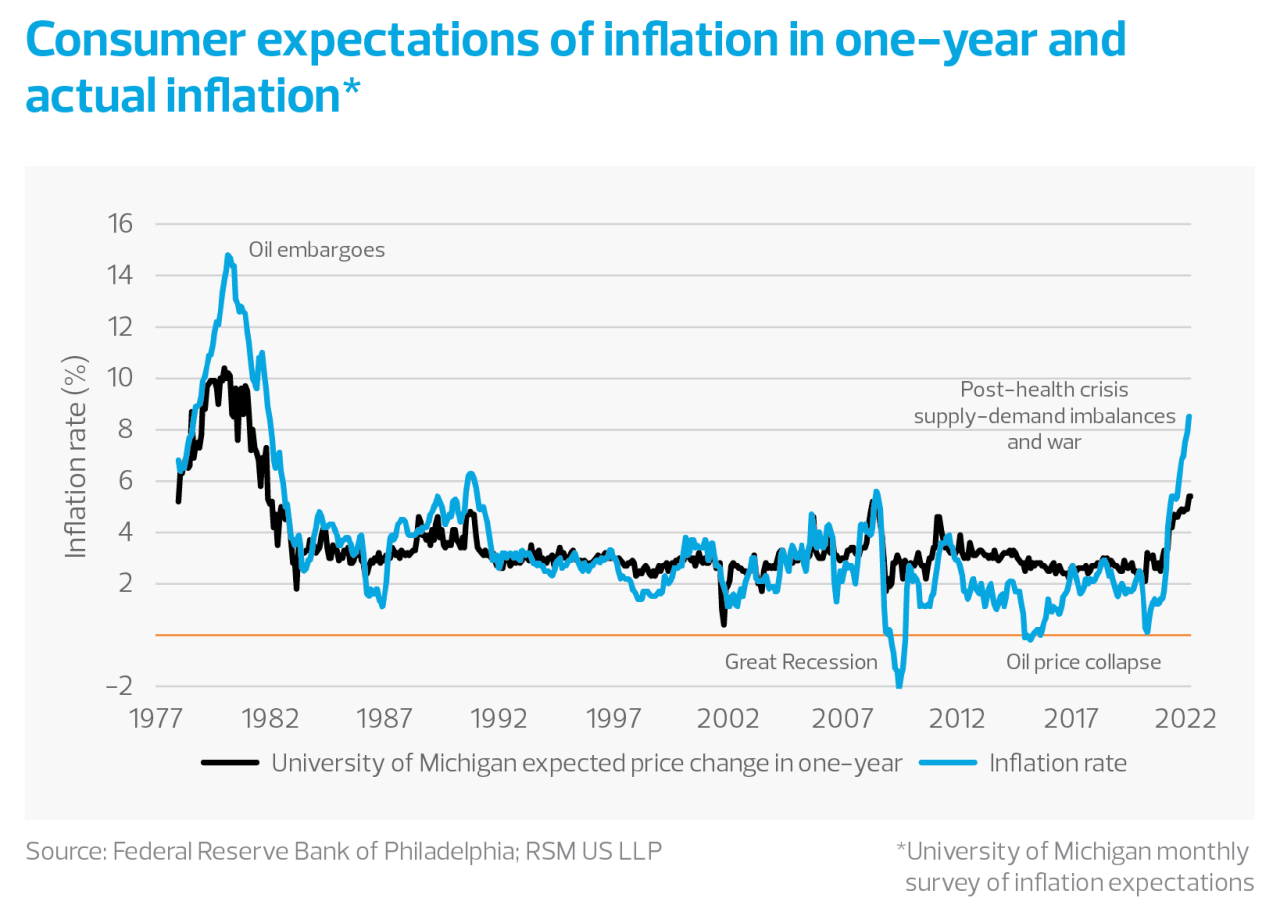

Given the extraordinary circumstances of the pandemic and the confidence that the monetary authorities among the developed economies would take reasonable action to constrain inflation, expectations for inflation remained low.

At the end of 2020, which marked the rollout of the vaccines and the acceleration of the recovery, the inflation rate was expected to remain close to the Fed’s 2% target.

That was after years of disinflation and a consumer sector accustomed to the availability of cheap goods and gasoline.

Even after the wartime oil price shocks sent the inflation rate above 7%, expectations remain subdued. As of April, inflation is expected to remain less than 3% over the next 12 months, reaching only 2.3% in 10 years. None of that is earth-shaking.