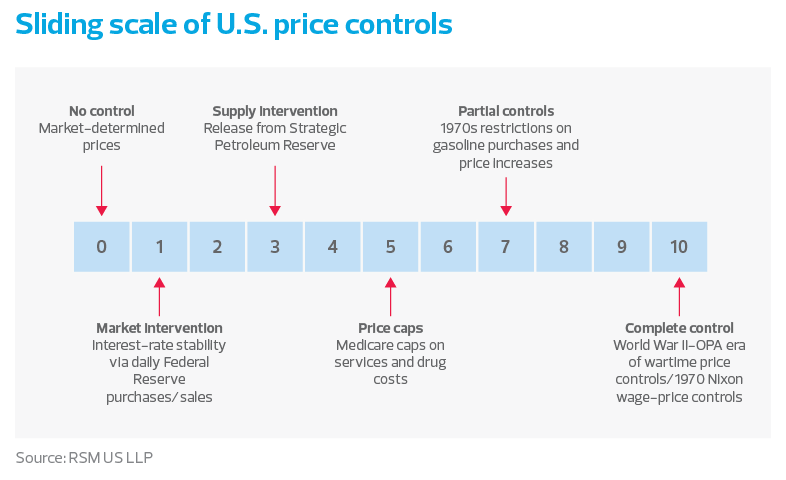

Price controls should be best understood as the range of costs influenced by various degrees of government intervention into markets.

They can be viewed as existing on a spectrum that moves from left to right, with those on the far left-hand side reflecting little to no government influence on prices and those on the far right-hand side reflecting a hard cap on the maximum that can be charged for a good or service.

So what does that look like? The minimum area of price control, and the most subtle, is the permanent intervention by the Federal Reserve into financial markets through its daily open-market operations. The operations desk at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York controls moves in the federal funds rate. It remains the primary policy tool of the Federal Reserve in determining the price of money for fixed-income securities from overnight rates out to 30 years’ maturity.

So the common assumption that the price of money along the maturity spectrum is set by the private sector is a gentle untruth. Interest rates are significantly influenced by the policy preferences of the central bank. We would assign a score of 1 to this subtle form of price control on our sliding scale, putting it at the far left of the price control spectrum.

In the middle of a spectrum, one might think about the cost of medical care. Health care, in general, accounts for roughly 18% of the American economy. For roughly the past century, the federal government has participated in managed care and, in some cases, set the price of medical care and drugs.

The current policy debate around setting a cap on the cost of insulin is a prime example of the long-term capping of prices on medical care. In our estimation, this would be assigned a score of 5, sitting midway between no control and total government control.

On the far right of the spectrum would probably be what most people would define as price controls when the government directly sets the cost of a good or service with little or no market participation in the setting of such costs.

The best example of this would be what the United States did during World War II through the Roosevelt-era Office of Price Administration. The OPA set prices in just about every market imaginable to support wartime efforts to run the economy at maximum output and to support wartime production under conditions of general resource constraints. If one wanted to purchase gasoline, rubber, sugar or coffee during the war, one had to do so under conditions of general rationing.

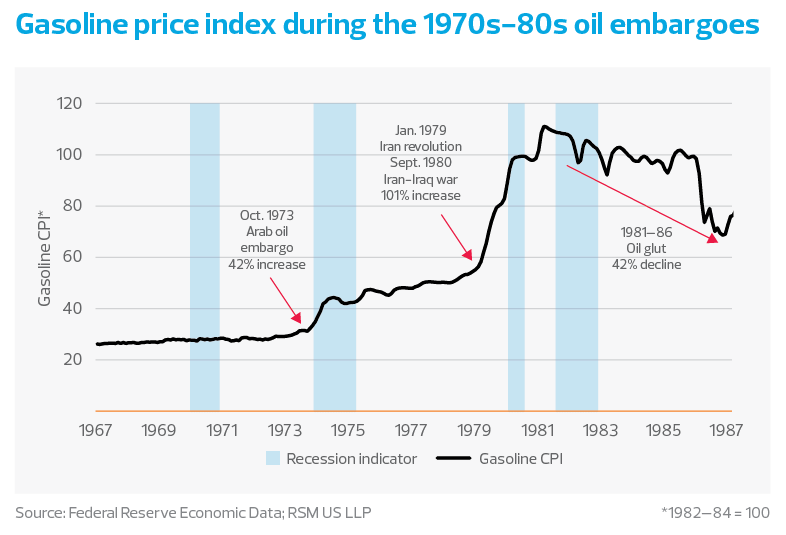

The only period of the modern era that resembled this was during the Great Inflation era of 1965 to 1985, when people in some states could purchase gasoline only on days that matched the last number of their license plates.

Short-run disruptions to the global oil and gasoline markets resulted in states like California, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania and Texas all rationing gasoline. In California in 1979, residents with license plates that ended in odd numbers could obtain gasoline on certain days and those with even numbers on others.

If hard price controls like those imposed during the war earned a 10 on our spectrum, the gasoline rationing imposed during 1979 would garner a 7. The Nixon-era wage and price controls would be a 10, right up there with Roosevelt’s OPA era.

1979 redux?

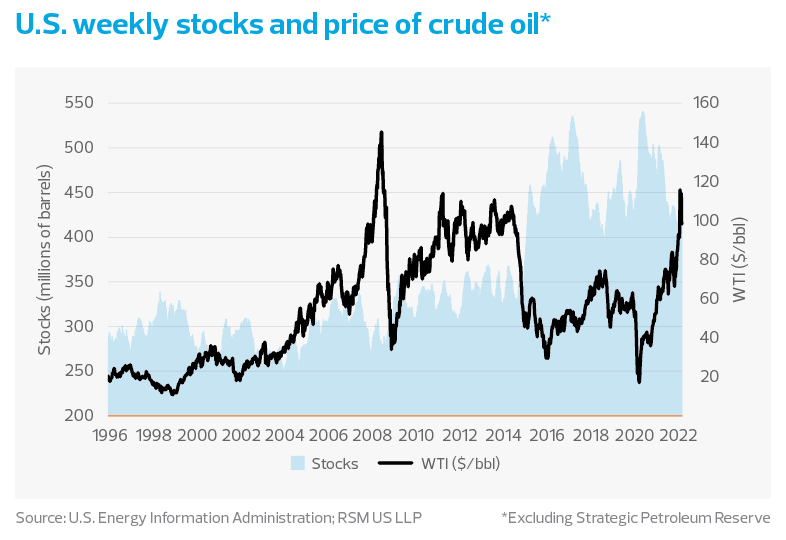

Rising energy prices are stimulating calls for the U.S. government to do something in response to the Putin price shock that caused the cost of gasoline in the March CPI to increase by 18.3%. Tapping the strategic petroleum reserves, selling more leases to drill on public land or in the ocean, and imposing price controls have all become part of that discussion.

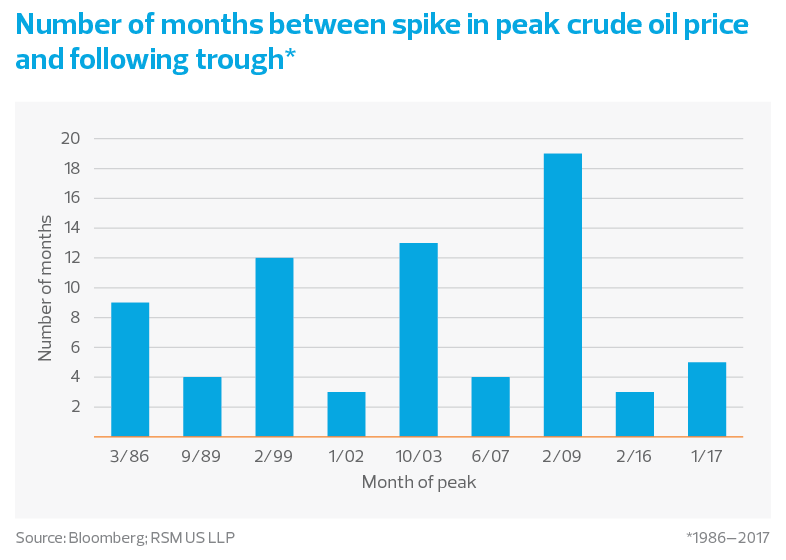

After the failure of ill-conceived price controls in the 1970s, the standard reaction to price spikes has been to demand intervention in the supply of petroleum products. The thinking is that any steps toward increasing supply would be met by increased production by foreign (and now domestic) producers that are more concerned with maintaining market share than profit.

In order to proceed in this conversation, it is important to note the current conditions within such policy decisions need to be made:

- North America is energy-independent for all practical purposes.

- Inflation and, in particular, energy-price inflation have reached 1974 and 1980 levels.

- The war in Ukraine will inevitably lead to lower fossil fuel supplies. Russia is second only to Saudi Arabia in production. The war seems likely to lead to higher petroleum prices, disruptions to the global supply chain and an economic slowdown spilling over into most if not all economies.

- Private financing has become more difficult for the fossil fuel industry. Lenders are unwilling to risk volatile pricing in a resource extraction business with a shrinking investment horizon and whose significant competitors are state-run enterprises that have shown their willingness to exert their dominant position.

- The developed economies are quickly turning to renewable energy. At some point, that will severely crimp the demand for fossil fuels.

- The price of petroleum is determined within a global marketplace that consists of producers, consumers and speculators. Each of these is concerned primarily with its own self-interest.

State actors are becoming involved. Lithuania has ceased all purchases of Russian energy, even though it is the cheapest source available. Germany is reluctant to endure the economic damages if it were to cut off Russia’s supply of natural gas and coal. Yet given the war’s direction in Eastern Europe, that may become a short-term reality.

And the European Commission is now requiring EU countries to fill their natural gas storage to at least 90% of capacity ahead of winter. The Biden administration has coordinated the release of oil reserves among

allied countries.

Lost economic output from the two oil shocks in the 1970s was estimated at $1.2 trillion in 1997-98 dollars by the U.S. Department of Energy. There will undoubtedly be economic losses in this current episode, but will these well-intentioned steps mitigate those costs? Let’s look at the track record of market interference.

Past instances of price controls

Market intervention in the U.S. economy would not be new. As we mentioned, wartime wage and price controls remained in place between 1942 and 1946.

Following the lifting of wartime price controls, inflation moved sharply higher through the end of 1948 and then eased. Nevertheless, it took the rest of the decade and beyond to retool for a peacetime economy and resolve supply and demand imbalances. (This will likely be the experience for Europe as it makes the transition away from Russian energy supplies and fossil fuels in general.)

In 1970, the Nixon administration implemented wage controls in an attempt to control inflation. Between 1974 and 1977, the Federal Energy Administration implemented oil allocation and pricing regulations in response to the first Arab oil embargo.

But those price controls didn’t work—the price of gasoline continued to rise, and price controls and stringent rules for purchases resulted in inefficiencies. In short, the Nixon-era price controls spectacularly failed.