The pandemic and the economic shutdown it prompted have injected an inordinate amount of noise into the economic data, making policy judgments, which are always difficult, far more challenging.

With those challenges, the risk of large errors that carry significant ramifications for the economy is embedded into the discussion around the risks linked to inflation.

So what are those risks? If policymakers exit too early from accommodative positions, they would almost certainly face another decade of disappointing economic and wage growth. But if they overplay their hands and continue the accommodative policies for too long, they risk overstimulating the economy and spurring unwanted inflation.

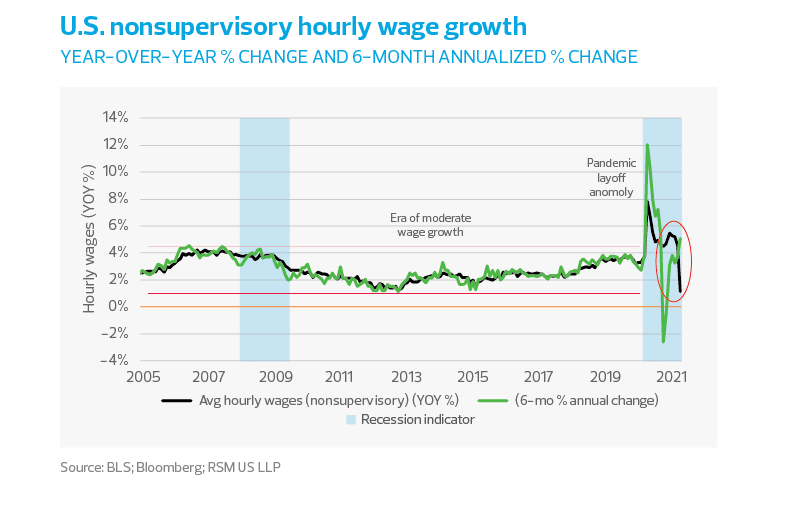

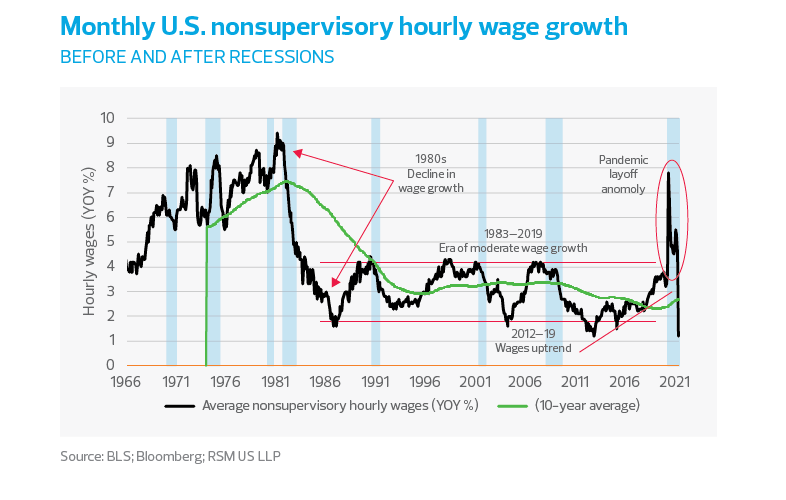

At the center of this discussion is wage growth. While we are observing some indicators that imply modest wage growth, at this point, it is more noise than signal and does not imply an imminent breakout in wage push inflation that would end the three-decade period of quiescence in pricing.

While we are observing some indicators that imply modest wage growth, at this point, it is more noise than signal and does not imply an imminent breakout in wage push inflation that would end the three-decade period of quiescence in pricing.

Cause for concern?

Government support for employers and direct subsidies through unemployment insurance have managed to maintain an income stream for low-wage workers. Spending among low-income households is up 22.6% compared to January 2020 largely because of those direct transfer programs, and it has put a floor under the economy during the pandemic. Furthermore, direct payments for child support beginning in July will help more parents afford child care and allow them to return to work.

MIDDLE MARKET INSIGHT: Direct payments for child support beginning in July will help more parents afford child care and allow them to return to work.

These payments, along with accommodative monetary policies, have stimulated a discussion around whether too much money is flowing into the economy and if that poses a risk of inflation.

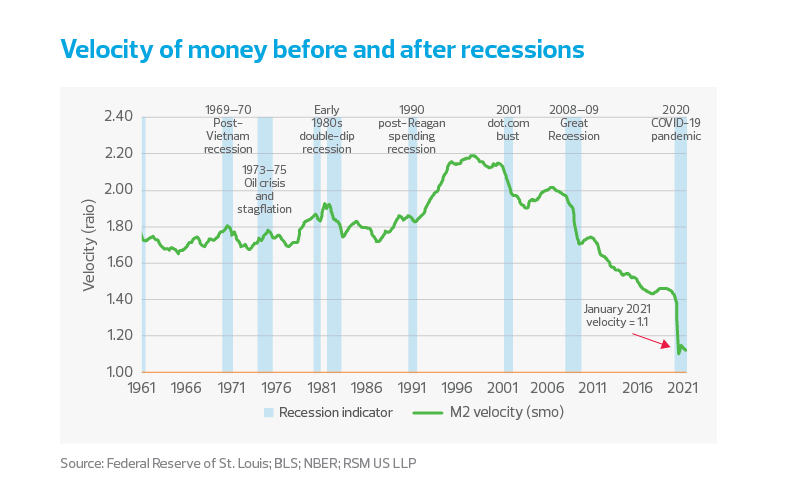

Given the increase in the M2 money supply from $15.4 trillion to $19.8 trillion during the pandemic, in addition to the $5.7 trillion in fiscal aid over the past year, this concern is understandable.

Transmission mechanism and expectations

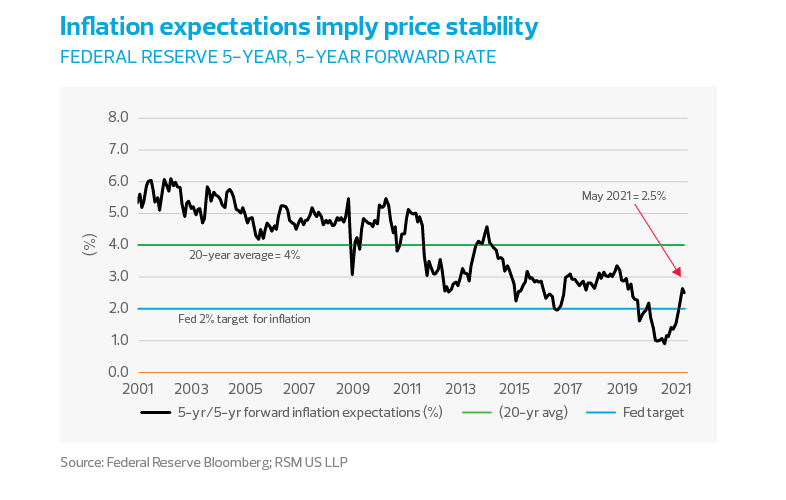

But there needs to be a transmission mechanism to cause that inflation. If one expects an increase in inflation, then one should expect an increase in the velocity of money—or the rate at which money changes hands—and a change in inflation expectations. A look at that is quite illuminating.