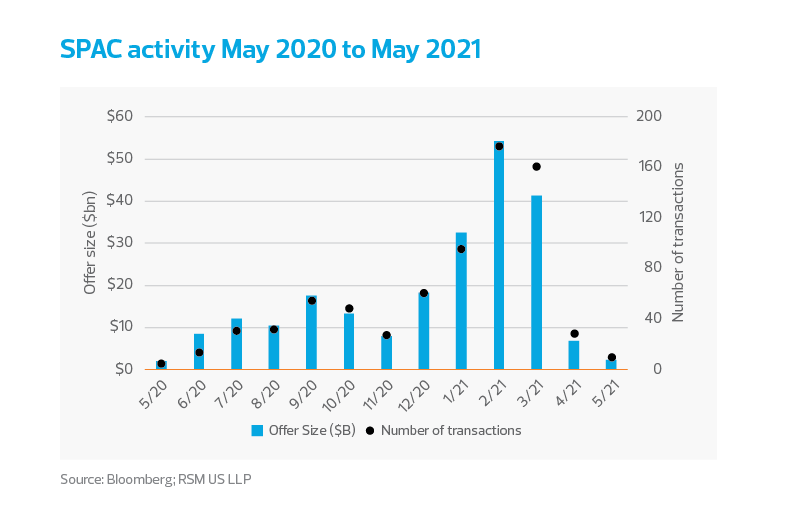

The pause in new SPAC IPOs may well turn out to be a positive for the evolution of this public listing alternative. The wintertime explosion of volume and dollar value of new SPAC IPOs may have simply run too hot to be sustainable. A steady flow of SPAC IPOs at a slower pace—one that matches the supply of private companies that are suitable targets to merge with a SPAC—may be good for rebalancing the market. Some enhanced regulatory scrutiny may also bring about investor protections and an alignment of interest with SPAC sponsors that could enable both retail and institutional investors to invest in SPACs with more confidence in the long run.

A steady flow of SPAC IPOs at a slower pace—one that matches the supply of private companies that are suitable targets to merge with a SPAC—may be good for rebalancing the market.

To be clear, SPACs are unlikely to disappear from capital markets despite the recent setbacks and some headwinds in the future. With more than 400 active SPACs looking for targets after the fundraising frenzy of 2020 and first quarter of this year, there is plenty of dry powder—about $178 billion as of mid-April, according to IHS Markit—looking to close deals before the 18-to-24-month deadline by which a SPAC has to complete a reverse merger with a private company to make it public.

Existing SPACs continue to announce merger transactions, although there are some indications that the soured sentiment may have slowed the pace and tempered the ease of locking down financing from private investment in public equity (PIPE). PIPE deals inject more capital in these so-called de-SPAC transactions in order to facilitate the acquisition of targets valued at price tags even larger than the cash raised from the SPAC IPO and to inject cash into the operating business.

Meanwhile, the future of SPAC IPOs is less clear. While several drivers have dampened interest in the current environment, the threat of more regulatory scrutiny might have relatively long-lasting effects.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) fired a warning shot on April 12 when it clarified how to interpret guidance about how SPACs account for warrants, a key feature of how SPACs incentivize and attract initial investors. The new treatment may require that warrants be recognized as liabilities instead of a component of equity, although fewer firms appear to be impacted than initially expected. The resulting accounting issues are not necessarily difficult to overcome, but they can be time consuming.

The Securities and Exchange Commission fired a warning shot when it clarified how to interpret guidance about how SPACs account for warrants.

The change may force some existing SPACs to restate their financial statements, which generally is a negative event for a public company. It also could slow the registration of new SPACs seeking to complete an IPO, as they may need to amend existing filings before their registration statements can be declared effective by the SEC. The warrant accounting change does not have any direct impact on the economics or cash flows of the investment vehicle and therefore is likely not the sole contributor to the slowed pace of SPAC IPOs.

The SEC also has vocalized its concerns pertaining to certain features of the de-SPAC transaction, specifically the practice of presenting forward-looking statements to entice investors to vote in favor of the merger transaction.

John Coates, the acting director of the SEC’s Division of Corporation Finance, released a statement April 8 arguing that the de-SPAC transaction is, in fact, the transaction by which the target company goes public and, as such, may be viewed as its IPO. In the traditional IPO process, presenting forward-looking projections is prohibited. Coates’ statement portends possible regulation concerning permissible use of financial projections and potential liability risk for dissemination of such information.

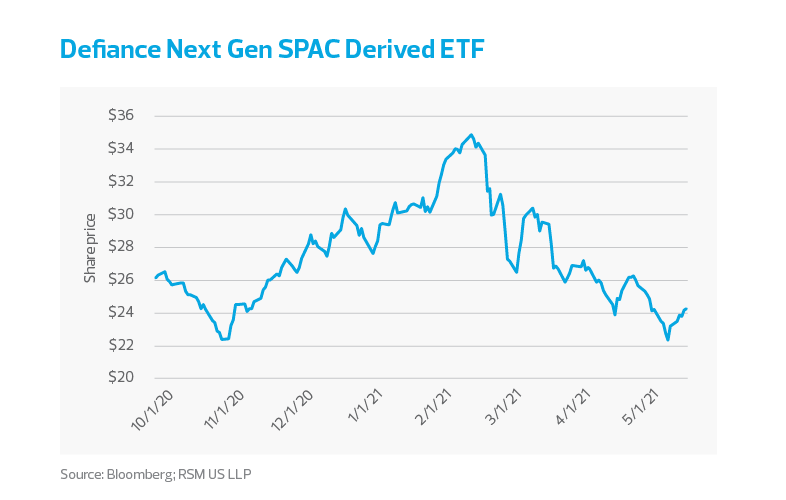

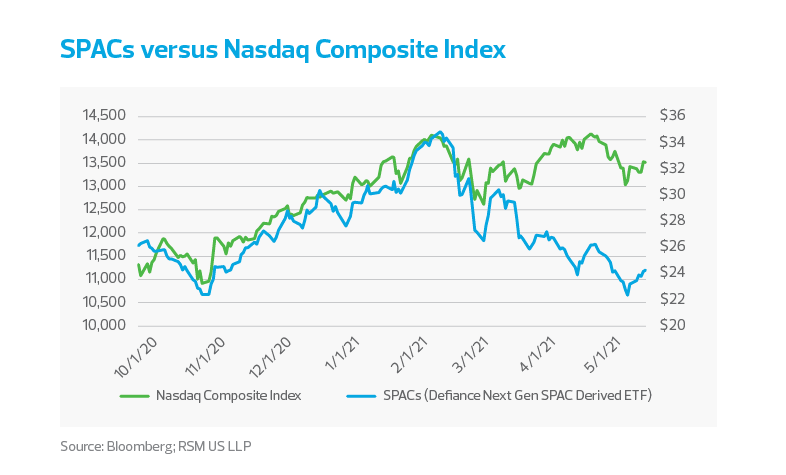

Aside from the SEC’s overhanging magnifying glass, the reasons for SPACs’ diminished share price performance are manifold. The drop from the mid-February peak to early March is closely connected to the drop in growth stocks, which was driven by market fears that interest rates would rise as a result of increasing expectations for inflation. In fact, the growth and tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite Index followed a similar trajectory over the same period. SPACs, by the nature of the target companies they pursue, closely resemble growth stocks.

From mid-March onward, though, SPAC stocks have continued their downward slide as retail investors’ interest retreated. Retail investors had been one of the driving forces behind the SPAC surge. Many searched for the next big startup in novel industries such as space travel, electric vehicles and other related technologies.