The inability of small businesses to secure loans early in the pandemic led to the MSLP.

Key takeaways

It was the Fed’s most direct intervention in the bank loan market since the 1930s.

The program supported more than 2,400 borrowers and co-borrowers with loans totaling $17.5 billion.

The inability of small businesses to secure loans during the initial shock of the pandemic motivated the Federal Reserve and the Treasury Department to create the Main Street Lending Program in March 2020.

It was the Federal Reserve’s most direct intervention in the bank loan market since the 1930s and 1940s, when it briefly lent directly to businesses.

The program was aimed at the missing middle in the commercial loan market—businesses too small to benefit from the Federal Reserve’s corporate credit programs but too large to qualify for the loans and grants available through the Paycheck Protection Program.

In the end, the program supported more than 2,400 borrowers and co-borrowers across the United States, with loans totaling $17.5 billion, the most of any Federal Reserve credit purchase facility, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

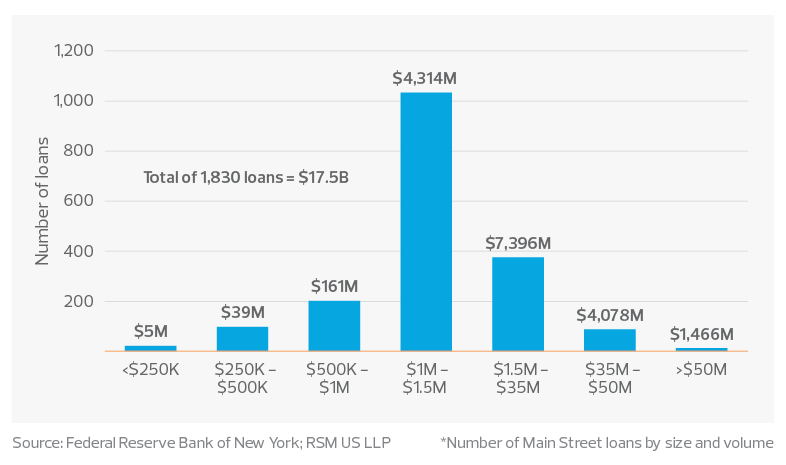

Over its six-month run, Main Street purchased 1,830 loans. Those loans represented a meaningful addition to the flow of credit, roughly comparable to the amount of lending by the largest banks over the second half of 2020 to borrowers with similar characteristics.

While some in the policymaking community saw the program as a disappointment because of the relatively small uptake in contrast with the potentially large resource pool that the Fed provided, we do not see it that way.

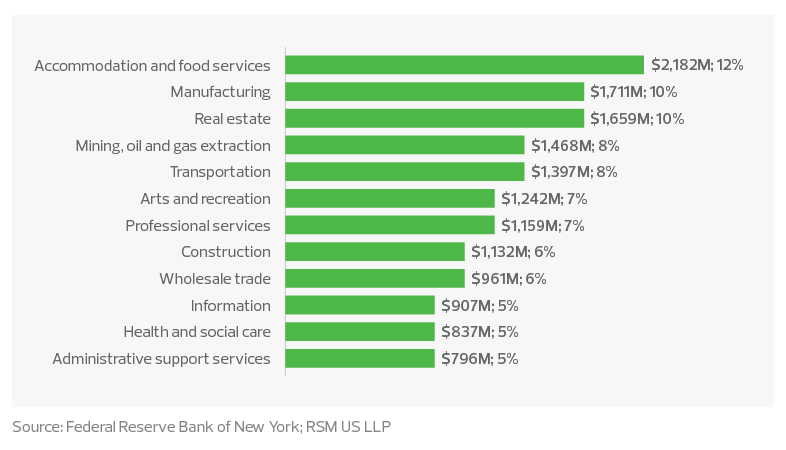

Rather, the disbursement of aid offered a lifeline to areas of the economy and industries hardest hit by the shutdowns.

Middle market insight

Over its six-month run, the Main Street Lending Program purchased 1,830 loans. Those loans represented a meaningful addition to the flow of credit.

The average Main Street loan was $9.5 million, significantly larger than the average loan under the Paycheck Protection Program. Main Street captured an important part of the middle market that would not have received aid otherwise and helped avoid an even worse employment shock. For policymakers, the Main Street program provided an important lesson in how to craft an aid program during a time of severe duress.

The missing middle

Tens of thousands of U.S. firms have more than 500 employees (the PPP cutoff) but are not rated to issue bonds. These firms instead depend on self-financing, banks or other intermediaries for credit.

As the pandemic took hold, the need for credit soared, as evidenced by the surge in bank business lending in the spring of 2020. Commercial and industrial loans rose by more than half a trillion dollars in the first few months of the pandemic, while other firms drew down their reserves.

The goal of Main Street was to assist businesses and nonprofits that faced credit constraints but were in sound financial condition before the pandemic, had good post-pandemic prospects, and were in a position to benefit from—and repay—a loan.

Main Street was intended to complement the Federal Reserve’s corporate credit and municipal lending facilities that supported larger businesses, states and municipalities.

Designing the program

It took four months to launch the program. Because of the importance of relationship lending for these businesses, policymakers were left without a readily available, standardized set of loan terms or credit metrics that could easily be converted into a term sheet and scaled for thousands of businesses.

Policymakers at the Federal Reserve and the Treasury settled on a loan participation program to support the supply of credit. Banks would be able to sell 95% stakes in eligible loans at par to the Main Street special purpose vehicle, with the credit risk shared between the SPV and lenders.

The loan participation model was built on three principles:

- Build on what’s there: The program leveraged lenders’ existing infrastructure for originating, monitoring and servicing loans, as well as their expertise in assessing and controlling risk.

- Reduce risk: The program transferred the bulk of the loans and associated risks from the lenders to the Main Street program, helping mitigate the acute economic uncertainty and risk aversion that was driving the tightening credit supply in the spring.

- Find a balance: Main Street allowed for an appropriate balance between reach and risk. The substantial risk bearing by the Federal Reserve promoted reach, while the residual bank risk bearing maintained some economic incentives for lenders to control risk.

Middle market insight

The goal of Main Street was to assist businesses and nonprofits that faced credit constraints but were in sound financial condition before the pandemic.

Terms of the loans

Loans were written with an interest rate of Libor plus 300 basis points with zero prepayment penalty. The high interest rate—relative to nonstressed conditions—provided an incentive for rapid repayment when conditions normalized.

Interest payments were deferred for one year, with principal payments deferred for the first two years of the five-year loans.

Finally, eligible borrowers were required to make commercially reasonable efforts to maintain their payroll while the loan was outstanding.

Eligibility

Main Street targeted small and medium-sized businesses with fewer than 15,000 employees or less than $5 billion in annual revenues (including affiliates).

According to the Fed’s analysis, these caps were deliberately set above those used for the PPP (500 employees) or other Small Business Administration lending (with size thresholds that vary by industry). But they were lower than the level at which a company might generally have access to financing in capital markets.

Lenders were given discretion on loan size and leverage based on pre-pandemic performance. These leverage limits had the effect of excluding some highly leveraged or unprofitable firms and became the primary mechanism for limiting risk to the program.

Most Main Street loans were $1.0 million to $1.5 million*

The program’s wide reach

The average 2019 revenue of participants was $34 million, with assets averaging $26 million. Pre-pandemic levels of leverage were relatively low.

- Need for the loans: Borrowers saw an average revenue decline of about $7 million during the first two quarters of the pandemic. This implies that Main Street helped many borrowers that were hit hard by the pandemic but were still solvent and viable.

- Size of the loans: The average loan was $9.5 million, substantially larger than the average PPP loan of just $101,000. This suggests that Main Street succeeded in targeting firms that were too large for the PPP but too small to access the bond market.

Federal Reserve officials note the program’s wide reach, with borrowers from nearly all states. State-level activity tended to correlate positively with increases in COVID-19 cases and increases in a state’s unemployment rate.

Main Street loan volumes by industry

Lenders

The lenders were nearly all small to medium-sized commercial banks in the $250 million to $10 billion asset range.

We can attribute this activity to the need for the community banking industry, which we deem vital to the commercial activity of less populated and rural areas.

A preliminary assessment

We are nearly three years into the five-year term of the Main Street loans. All of the loans remain active.

The Main Street program became the largest purchase facility operated by the Federal Reserve. The Fed’s assessment is that many Main Street borrowers were hit hard by the pandemic, and lenders indicated they made loans they would not otherwise have made, all in line with the goals of the program.

The takeaway

Lessons learned will provide guidance for Treasury Department and Federal Reserve policymakers facing a future crisis.

- Speed: The program was operationally complex and took four months to set up, with subsequent revisions. This reflects the bespoke nature of the C&I loan market for small and medium-sized businesses and the fact that the Federal Reserve had not undertaken commercial loans since the 1940s.

- Reach and risk: Binding leverage limits, relatively inflexible loan terms, security and priority requirements, and limits on refinancing all limited risk, but did so at the expense of the program’s reach.

So just as monetary policy has evolved and arguably improved with each passing crisis, the experience of the pandemic should provide guidance for future policy.

RSM contributors

Q2 2024 Middle Market Business Index (MMBI)

Sentiment improves as firms look to invest

Key findings:

- The MMBI rose to 132.0 in the second quarter from 130.7 in the prior period.

- Forty percent of senior executives indicated that the economy had improved.

- A majority of executives intend to boost capital expenditures over the next six months.