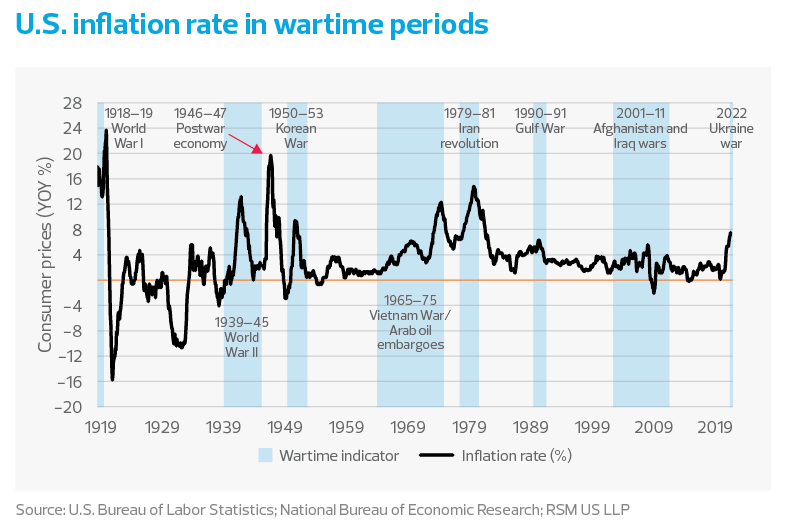

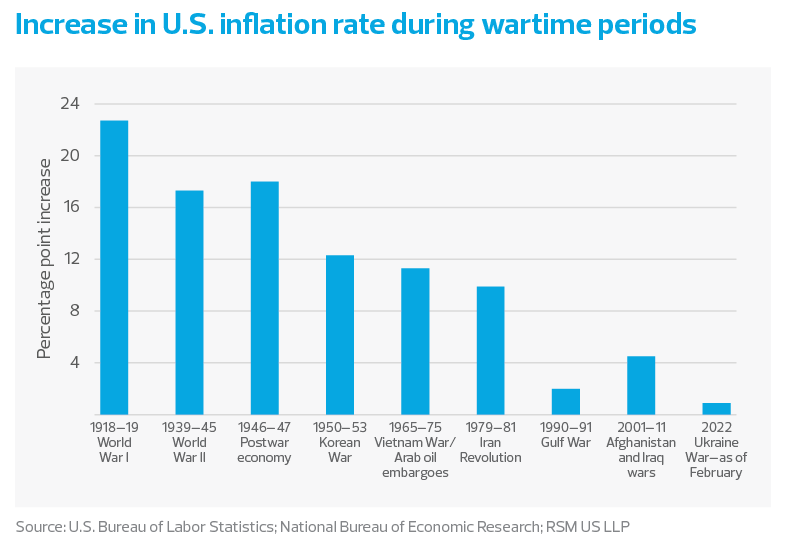

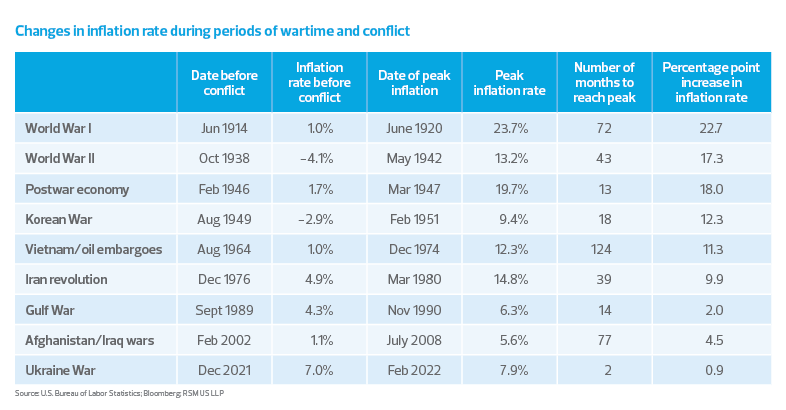

Inflation rises during war and economic conflict. Price dislocation, price controls and self-rationing are facts of life during wartime.

Today, with inflation at a 40-year high and a policy rate near the zero boundary, policymakers face significant constraints as they try to find ways to mitigate rising costs on American households that are conditioned to general disinflation.

Over the past century, price instability reached its highest level during the two world wars and then again during the two consecutive economic wars declared by Mideast oil producers in the early 1970s and 1980s.

We have most likely arrived at a turning point where elevated inflation will define the economic narrative for several years. That may require much higher interest rates than have been observed in recent years and will diminish the probability of central banks achieving a soft landing of the economy.

The probability of a recession will most likely jump from the current 15% to roughly one in three as the economic data is released over the coming weeks.

While we think the current price shock will shave roughly 1 to 1.5 percentage points off growth over the next 12 months, it should not result in a general recession in the United States, though it will almost certainly spur a recession in the European Union.

The primary difference is the underlying resilience of the American economy, as demonstrated in the recovery from the pandemic, along with a reduced dependence on Russian energy and commodity exports. These factors should lead to a slowing of the economy, but not to an economic contraction.