What happens when a real estate investor does not look at changing consumer preferences when undertaking a new project? More often than not, it ends in disappointment, and lost money.

One project that is heading down this path is New Jersey’s American Dream megamall. The unfinished property, which has cost investors about $2 billion so far, is falling well short of the $1.9 billion in gross sales it expected to generate in its first year. Now investors are having a hard time meeting the project’s mounting debt obligations.

So how did this project end up in such a big hole? Though there are many reasons, a big reason is a failure to appreciate changing consumer preferences, some of which were already underway when it was conceived, and a little bad luck.

The history

The tortured history of the American Dream is an object lesson in how ambitious plans with the best of intentions can go awry. The megamall was dreamed up in 1994 by the Mills Corporation, a real estate investment trust—right around the peak of America’s love affair with malls. In 1990, a record 19 new malls opened in the United States.

The plan was as expansive as it was expensive: To build a commercial development in the swamps of the New Jersey Meadowlands that would have 2.1 million square feet of retail space, 1 million square feet of office space and a hotel. If you build it, the thinking went, they will come.

As malls began to struggle, retailers started to develop their e-commerce offerings, and, in the physical world, favored stand-alone big-box stores.

And so it was with great fanfare that Meadowlands Mills was announced in 1996, but it quickly encountered resistance from environmental groups that objected to its location in the wetlands.

The state would eventually bless the project, and after delays, the project gained new life in 2002 when the New Jersey Sports and Exposition Authority, which wanted to move the New Jersey Nets out of their arena at the time, asked for proposals from developers. The NJSEA ultimately selected a proposal from the Mills Corporation in connection with Mack-Cali Realty Corporation.

The project seemed to be on track and even got a new name, Xanadu. The developers broke ground in September 2004.

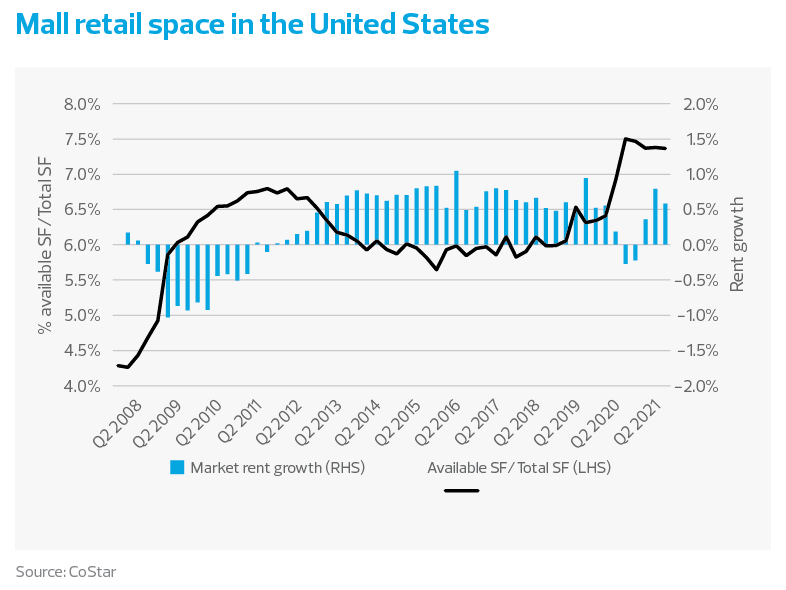

But around that time, America’s fascination with malls was fading. Consumer preferences were changing as shoppers began to go online and shy away from malls, many of which had not been renovated in decades. Besides, there was a growing perception that malls were becoming dangerous, even though there was little or no empirical data to support that claim. Retailers, in response, began to develop their e-commerce offerings, and, in the physical world, favored stand-alone big-box stores—think of Best Buy.