Wage increases and rising inflation are now of paramount concern to policymakers and businesses.

While conditions are not yet ripe for the kind of wage-price spiral that wracked businesses in the 1970s, the economic growth and emboldened labor market of the past year require a different policy response than the previous two business cycles.

For the Federal Reserve and Congress, that means striking a careful balancing act of reining in inflation while preserving hard-won wage gains among the nation's workers is no easy task.

To this end, monetary authorities have started to take measured steps to contain price increases while not crimping advances in productivity or growth. At the same time, we would hope that Congress would create incentives for businesses to address shortages of housing and energy that are pushing inflation higher.

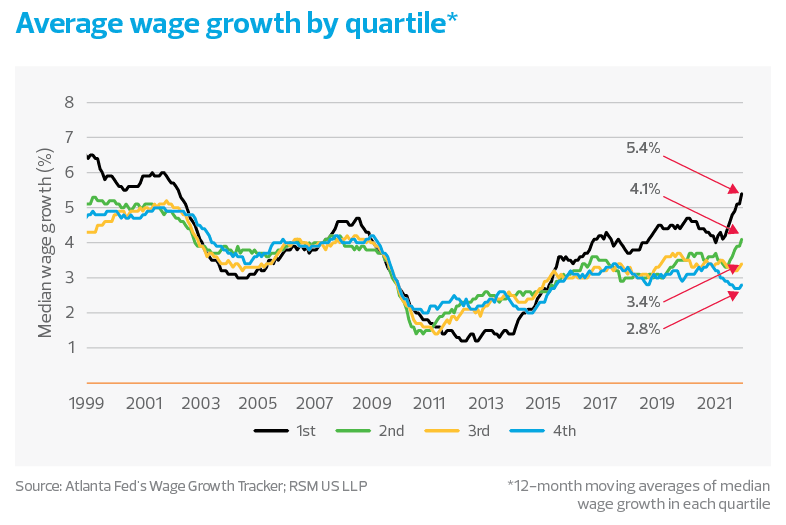

Make no mistake: The recent wage increases are not high enough to pose an immediate risk to economic stability, corporate profits or inflation. Instead, the rising wages have been supported by higher productivity among businesses.

Productivity and wages

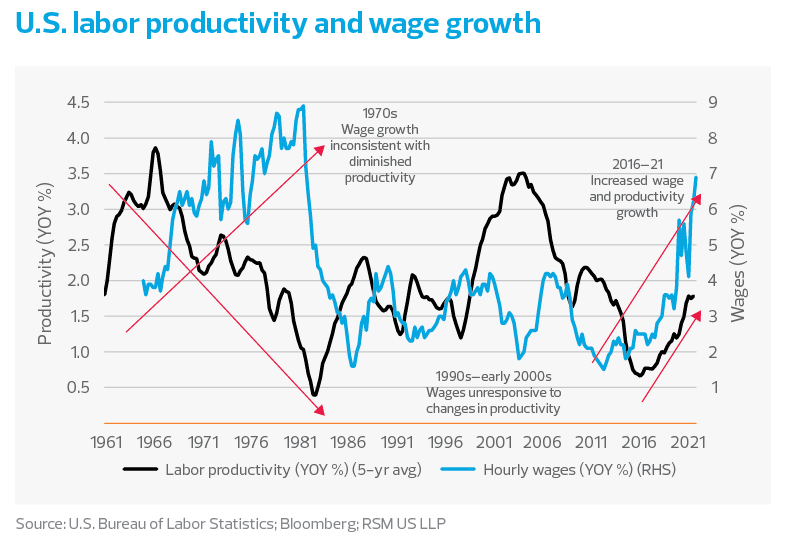

The economy can support higher wages as long as productivity increases at a faster rate. And this has indeed been happening. Productivity has been increasing since late 2016 because, in no small part, of the private sector continued investment in its competitiveness.

Consider corporate profits. The 4% increase in the employment cost index during the fourth quarter of last year and the near 7% increase in average wages have yet to put a dent in those profits. This implies that productivity is rising as the economy booms.

In the 1970s, by contrast, cost-of-living increases were built into labor contracts, and wage growth was unresponsive to changes in productivity. But this time around, the pandemic has become the catalyst for a significant shift in the labor market, with wages in the private sector now more a function of the supply and demand for labor and its productive abilities than in previous generations.

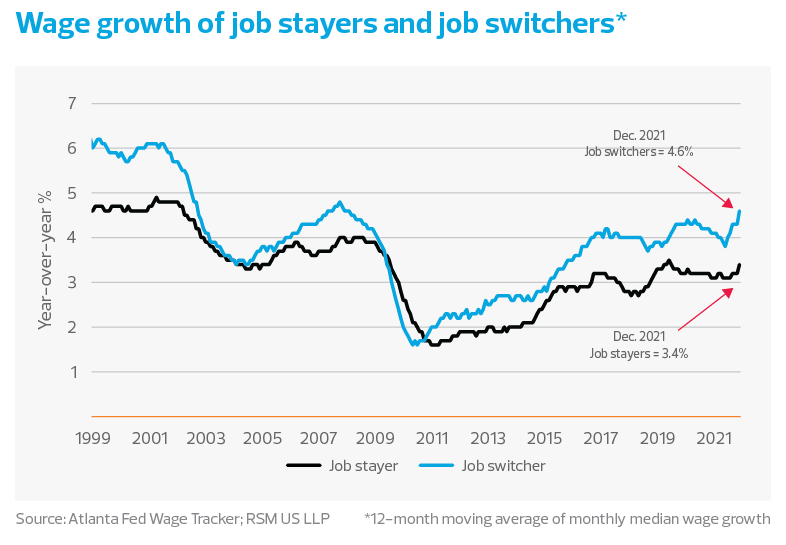

During the fourth quarter of last year, nonfarm productivity increased by 6.6% amid a 9.2% increase in overall output. For businesses, the cost of labor should correspond to its contribution to profits, with labor churn a welcome sign of engaged employees working their way up the income ladder. As firms experience an increase in productivity and profits, they are in a position to retain their workforce via higher wages and salaries.