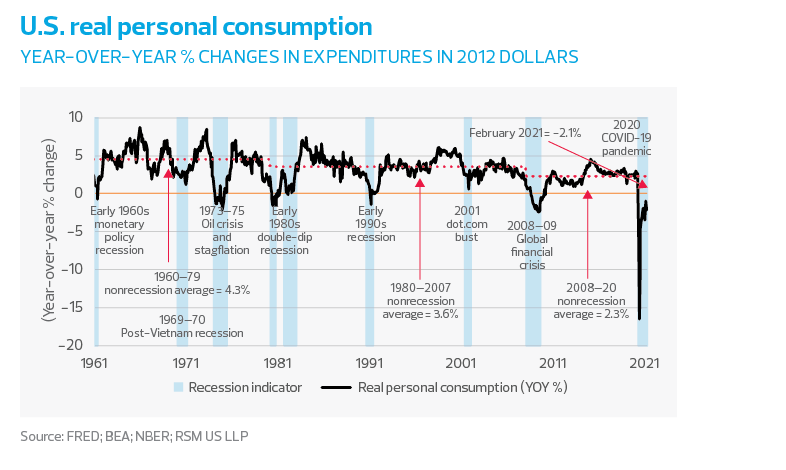

An avalanche of spending is waiting to be unleashed by the American household. Add that to the expected investments by the corporate sector to improve their productivity, and the result is a robust consensus forecast of 6.4% growth in gross domestic product—RSM predicts 7.5%—for this year. And that number will most likely be upgraded following the blowout March retail sales data, as well as the robust personal income, spending and savings data to close out the first quarter.

The strong recovery will depend on the efficacy and distribution of the vaccines, as evidenced by the coronavirus outbreaks afflicting numerous states. But we are confident that the year will end with the unemployment rate as low as 4.1% and the economy growing by 7.5% on a yearly basis, which is enough to support 10-year Treasury yields at 1.9%.

People have had enough of this pandemic, and are eager to have a beer and pizza at their favorite joint or go to an NBA playoff game. The pictures of London’s pubs—finally open again after the U.K. beat back the virus’ resurgence—provide a more compelling narrative than the economic data perhaps ever can.

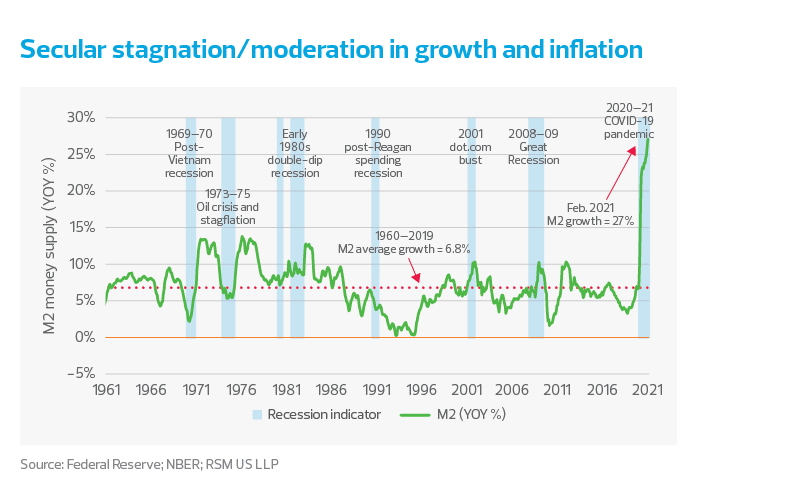

Yet with millions of people still out of work and living on limited incomes, where will the spending money come from? That simple question deserves a nuanced answer. The policy mix pursued by the fiscal and monetary authorities early in the recovery may seem to some like pushing on a string and risking inflation.

We do not agree. The mix of savings, pent-up demand for services and what we think will be an increase in productivity-enhancing investments by businesses will provide just the opposite. We see a multiyear period of above-trend growth, with two dynamics in play:

First, the trade war and the pandemic have afflicted different parts of the economy at different times. The manufacturing sector—which was in recession before the pandemic pushed the whole economy over the edge—appears to be growing once again. Employment in the goods-producing sector has already reached 95% of pre-pandemic levels.

And employment and spending among the white-collar set—those who were able to work at home—proved to be resilient with the maturation of online shopping, which has supported a segment of the service sector. Our colleagues at tracktherecovery.org think that households with more than $60,000 in income transitioned into recovery, and we agree.

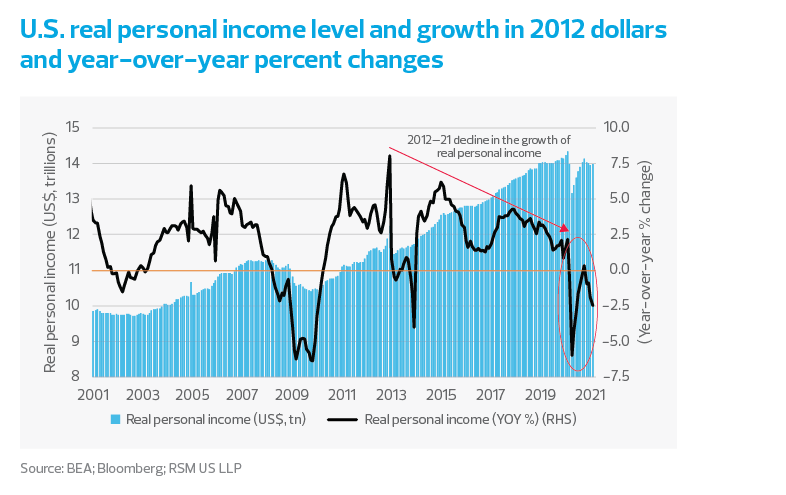

Second, the shock from the pandemic has led to a much stronger fiscal and monetary response than if the downturn had been limited to manufacturing. Income streams for low-income households have been supported and will continue to improve as expanded child care benefits begin in July. Low-income households tend to spend all of their income, and the multiplier effect of income support for those households is greater than for upper-income households. This is not only a function of accommodative monetary policy, but is also a result of nearly $6 trillion in fiscal aid, or roughly 26% of GDP, to address the pandemic.

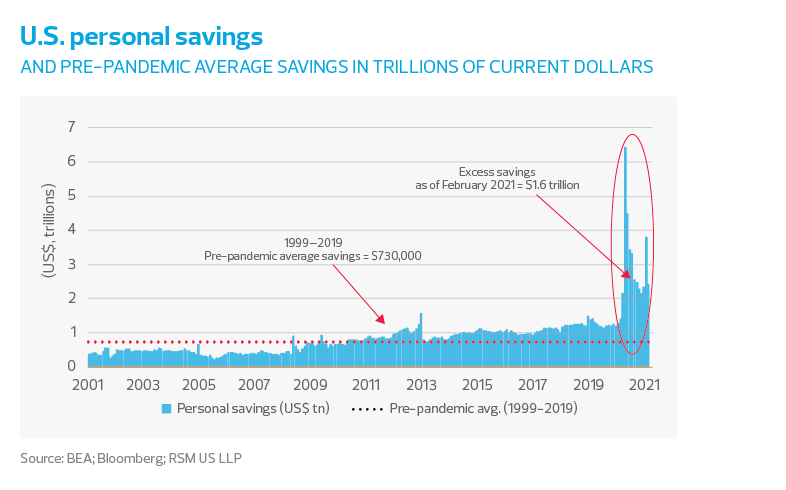

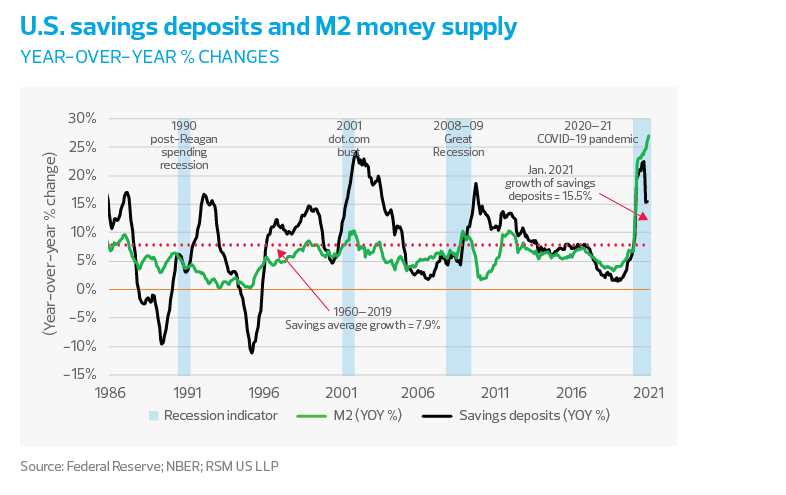

So we would argue that increased spending this year will come from a labor force that will be getting back to work, from government benefits that will continue to support lower-income households, and from the use of the $1.6 trillion in excess household savings compared to the pre-pandemic average of $700 billion.

Because savings can be a drag on the economy, we’ll discuss the origins of the huge increase in household balance sheets and how that might form the basis of a sustained recovery.

Savings, income and spending

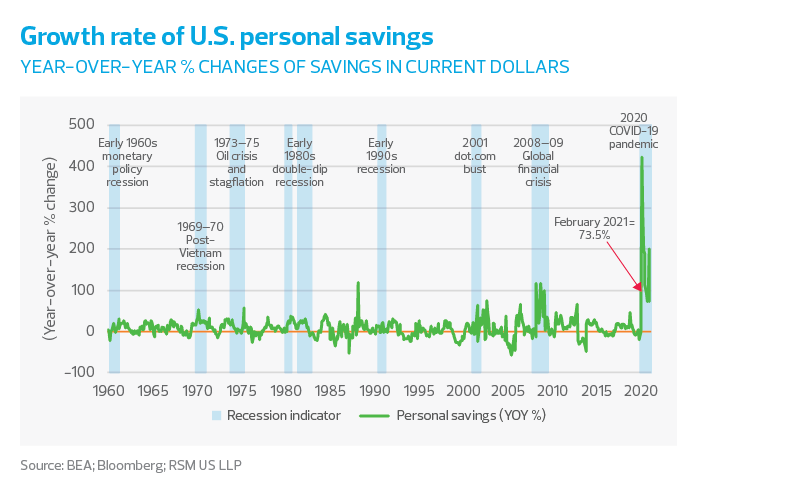

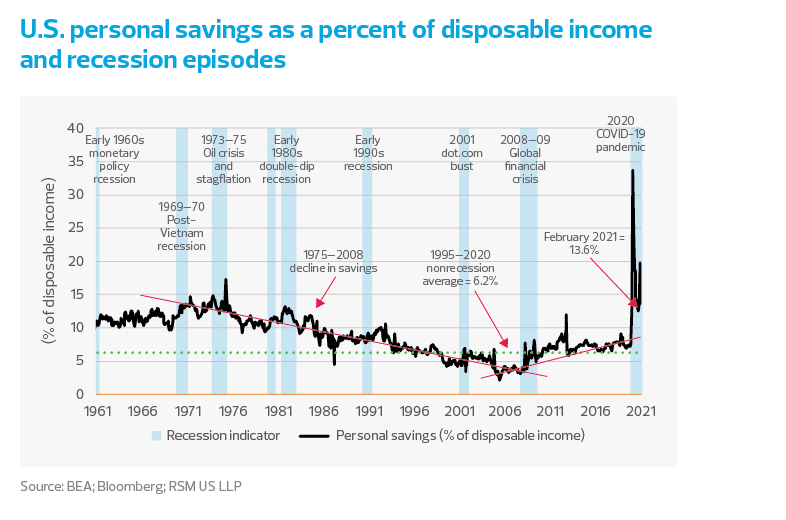

Let’s start with the outsized increase in personal savings last year that, no matter how you slice it, took more than $5 trillion off the table at the depths of the pandemic. Twelve months later, savings remain 73% higher than pre-pandemic norms.

That increase in savings is substantially lower than the 400% increase that developed in April 2020, when no one really knew if the pandemic could be contained. But note that for the next 12 months, those year-over-year comparisons will be distorted by base-year effects.