The probability of the economy and financial markets returning to their pre-pandemic state is quite low. Nowhere is this more evident than in trying to estimate valuations of the U.S. dollar. Despite the robust rebound in consumer demand, a sluggish external sector and pandemic-induced economic distortions add a worrisome element to the breadth of the recovery and to the value of the dollar.

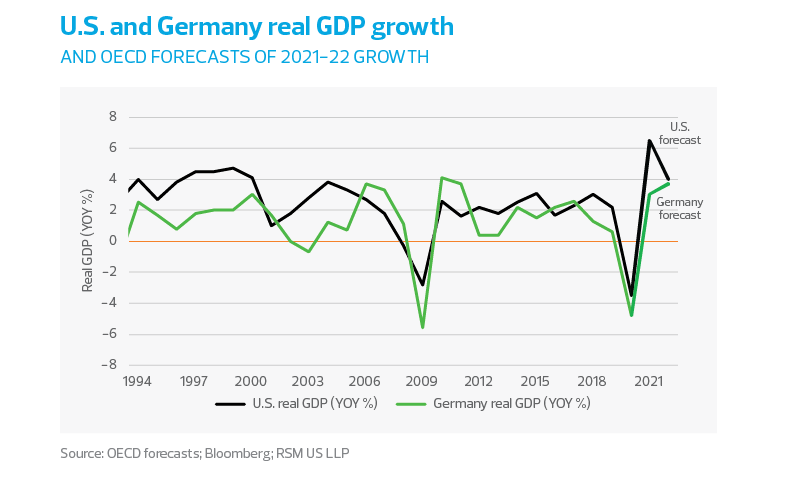

There is good reason to think that the United States will be the first of the developed economies to close its output gap, with increased demand in coming months that will turn recovery into economic expansion.

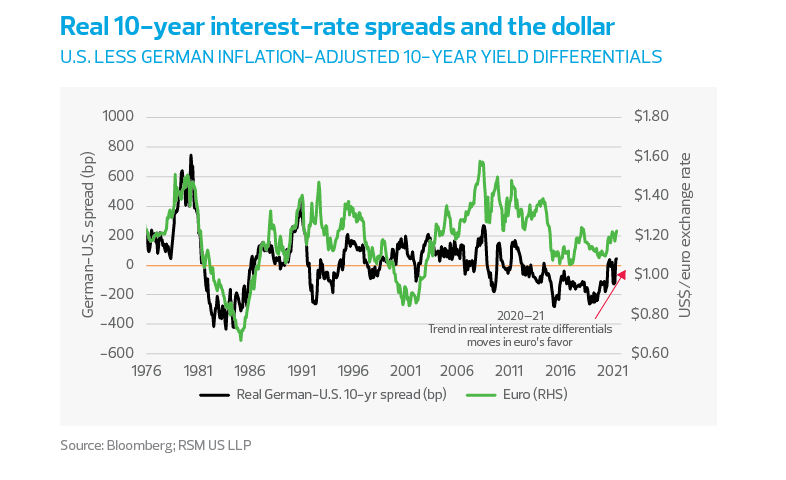

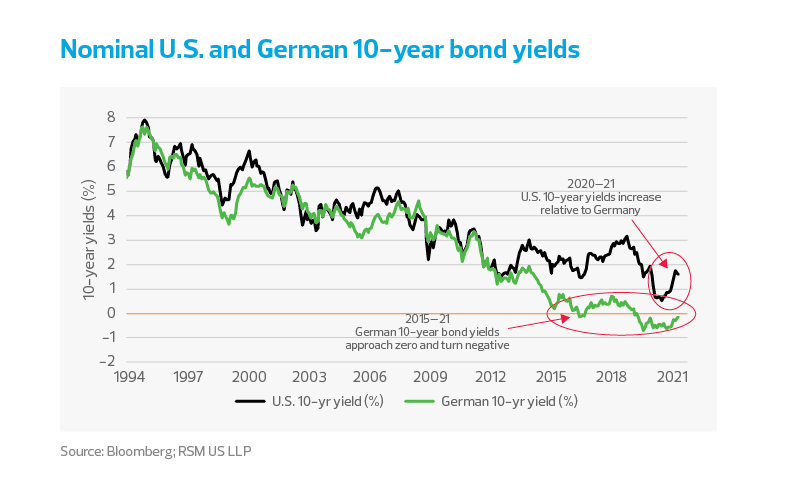

We are anticipating the highest rates of growth in gross domestic product since the 1980s, supporting 10-year interest rates reaching upward to 1.9% over the course of the year. And one must note that those high nominal interest rates must be coupled with real interest rates that are negative in the United States and likely to grow more so in the coming months.

For this reason, we expect that the value of the greenback will experience notable volatility with modest downward pressure, causing the dollar to decline in value against major trading currencies.

MIDDLE MARKET INSIGHT: For middle market firms with significant exposure to the Canadian dollar and Mexican peso, downward pressure on the greenback implies modestly higher prices on the margin.

For middle market firms with significant exposure to the Canadian dollar and Mexican peso, this implies modestly higher prices on the margin.

Yet there is a lot of ground to cover before we can declare global victory over the pandemic. There is still too much uncertainty regarding the rapid spread of the virus and its variants in India, South Africa and Brazil, and the risk of spread to the unvaccinated American public.

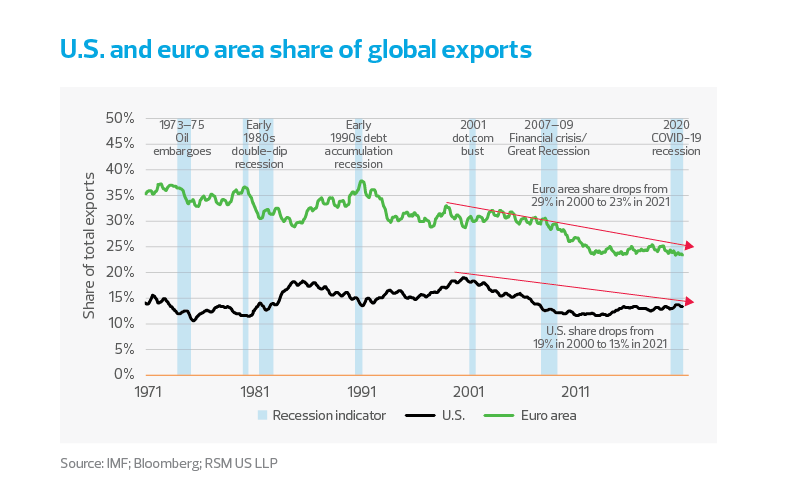

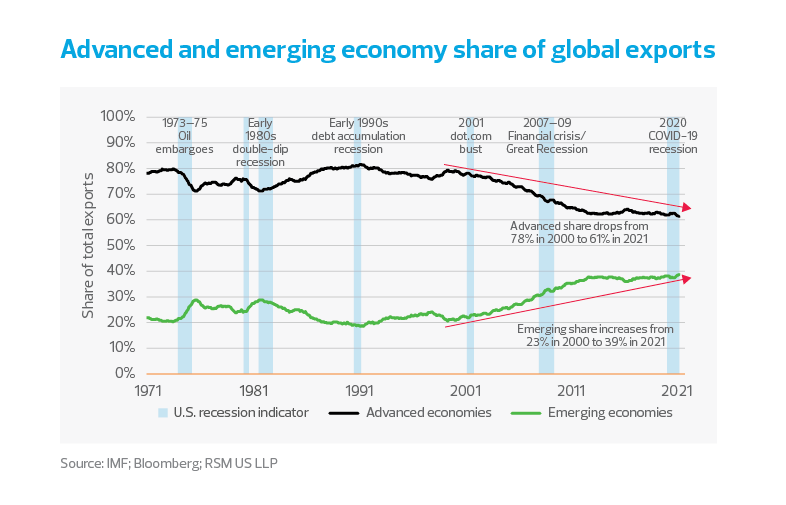

In addition, long-term scarring to the U.S. labor force; the lack of immigration and a low birthrate; and the loss of U.S. market share during the trade war might prove to be unrecoverable in the short term, and difficult to mend over the long haul.

In the next sections, we’ll outline the difficulty in forecasting the dollar in an environment in which the efficiency of the global supply chain has undeniably become part of commercial life and the United States is no longer the only major exporter to the world. And we’ll discuss the efficacy of the debate over dollar strength and the economy, branding that discussion more as a holdover from an earlier time.

MIDDLE MARKET INSIGHT: Though U.S. imports appear to be making up for the dearth of consumer spending during the pandemic shutdown, exports of goods remain underwater.

Relative growth and the dollar

Given expectations by international economics officials that the U.S. economy will be the first among developed economies to expand, doesn’t that imply that the dollar will be stronger?

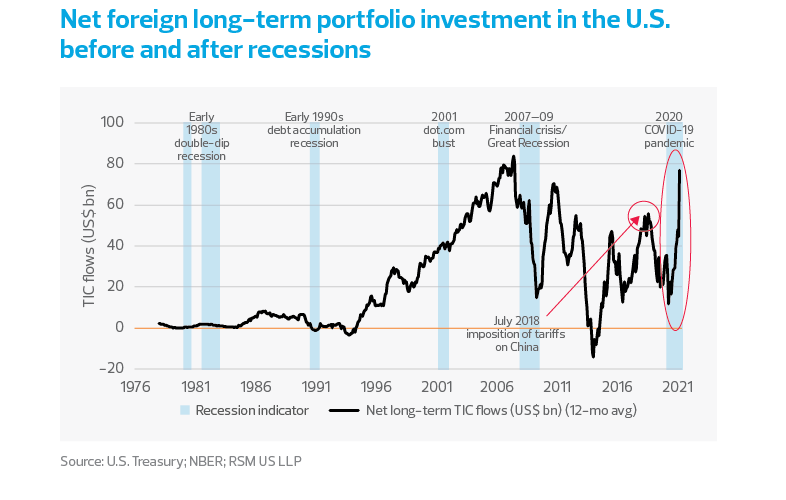

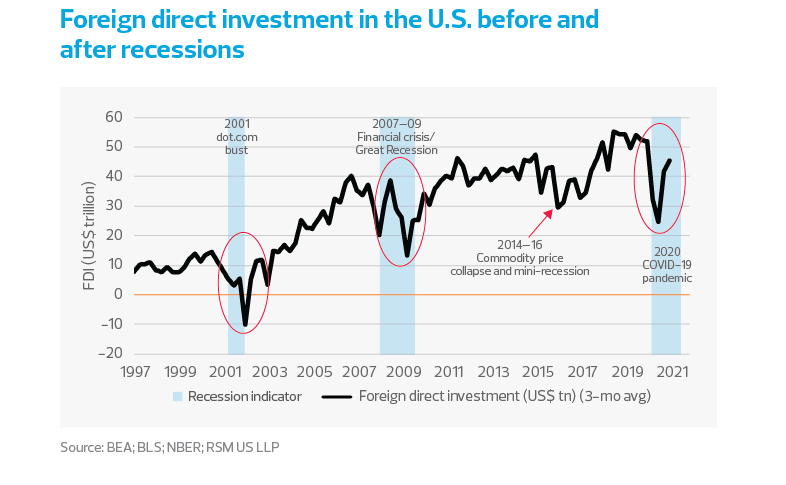

That assumption is not necessarily true. The value of the dollar, like any other commodity, depends on the demand for dollar-based assets–both financial and physical–and the transactional use of the dollar in commercial activity. The demand for dollars depends on a host of factors, both domestic and foreign. There have been several recent examples where the relationship between domestic growth and the value of the dollar has been inconsistent.

The value of the dollar will be determined by its use as a vehicle of commerical exchange and by the demand for U.S. goods and ideas. The foundation of that demand will be determined by the stability of the economy and society, and the laws and institutions that guarantee that stability.

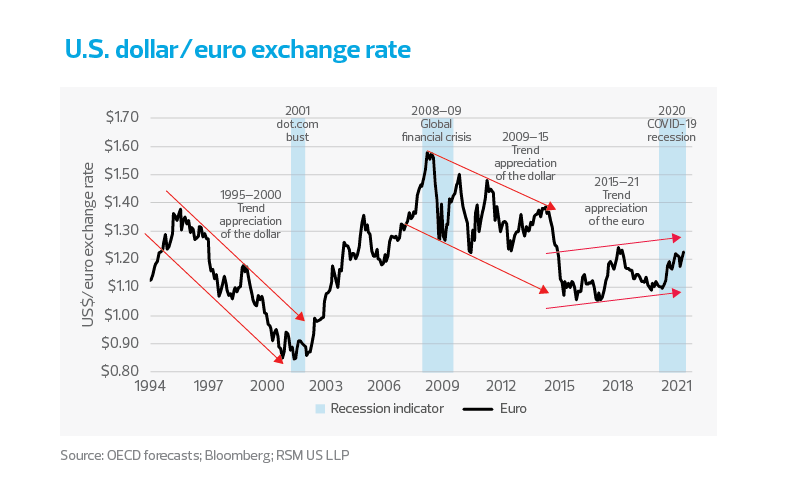

For instance, the U.S. economy took off during the mid-1990s as the digital age began. Investment was pouring into the technology sector, and the dollar appreciated versus the deutschmark, which was the European benchmark at the time. That era of dollar strength ended with the thud of the 2001 dot.com bust.

The dot.com bust happened at the same time as anxiety over European unification and its single currency were overcome, followed shortly by the attacks on the United States and the onset of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The dollar weakened versus the euro until the 2008-09 financial crisis.

With the Federal Reserve cementing its role as lender of last resort to the world during the financial crisis, the dollar started a period of appreciation versus the euro despite the reluctance of American fiscal authorities to juice the tepid economic recovery from the Great Recession. To be fair, some of the dollar’s early strength was because of the ongoing saga of the European debt crisis, which was more than enough to scare off investors.

In the second half of the latest decade, Germany’s economy was growing at a five-year average rate of only 1.6%, having been dragged into the U.S. trade war and the global manufacturing recession. From 2015, the U.S. economy grew at an average rate of 2.5% before slipping a bit in the last quarter of 2019.

Yet despite the attractiveness of U.S. equity returns, the euro range-traded during 2015-16 before entering a jagged uptrend versus the dollar. The euro has appreciated by 18% since January 2017 and then in the latest episode by 14% since the pandemic shutdown and equity market collapse of March 2020.