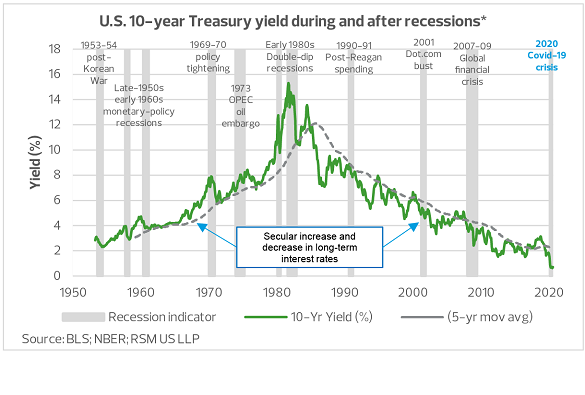

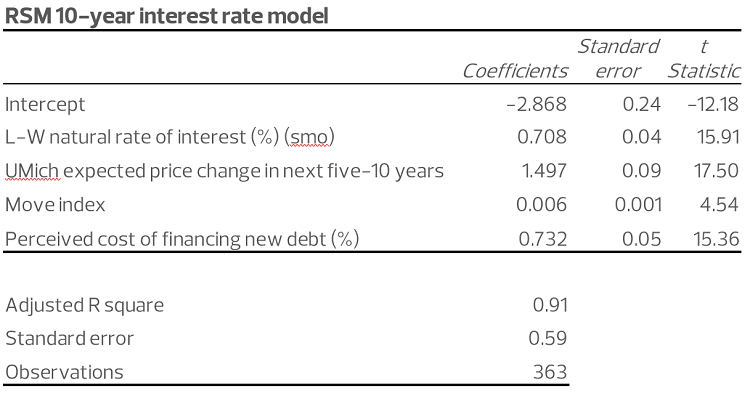

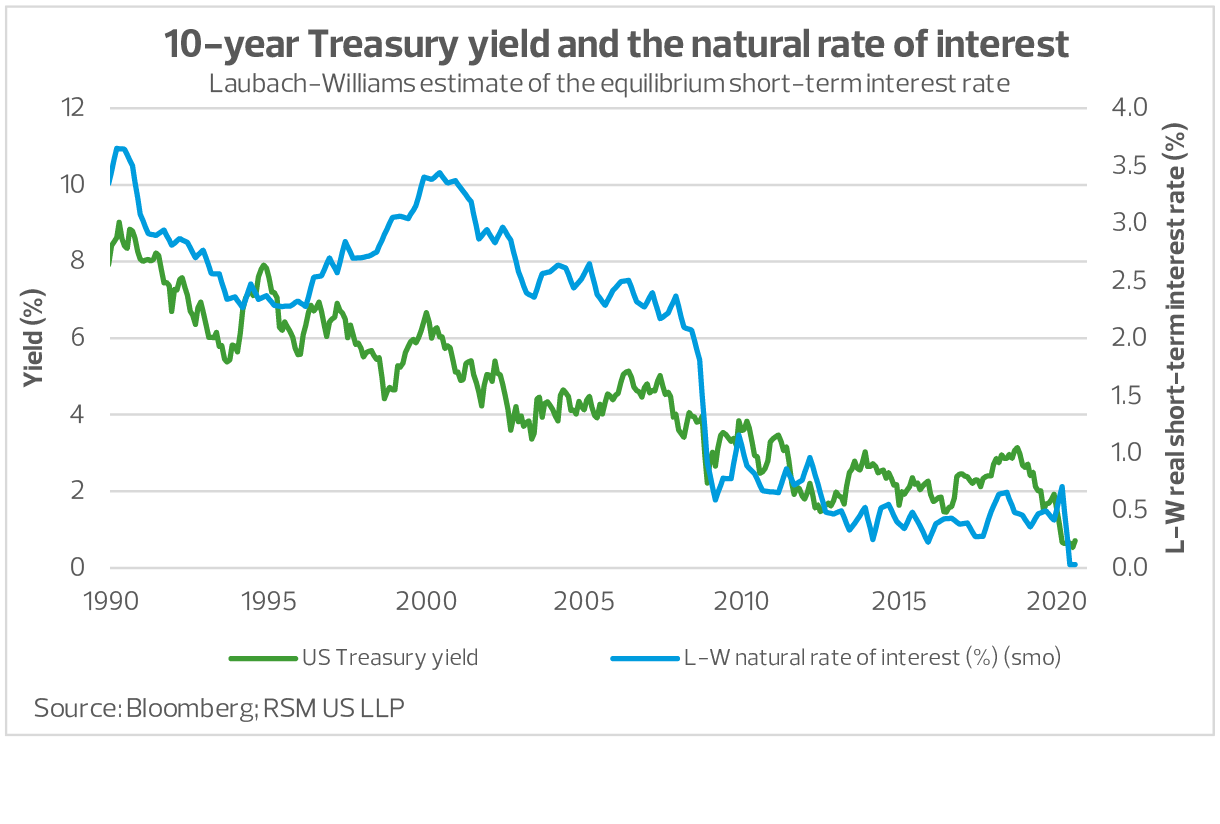

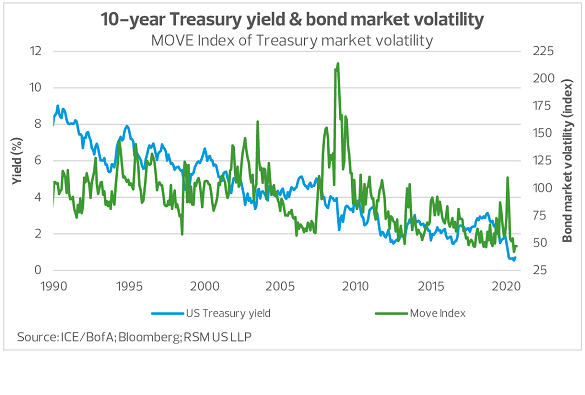

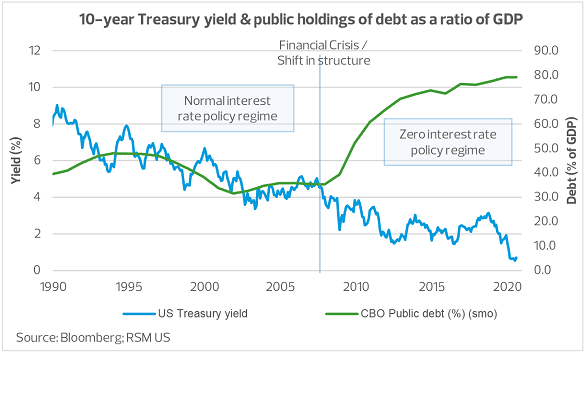

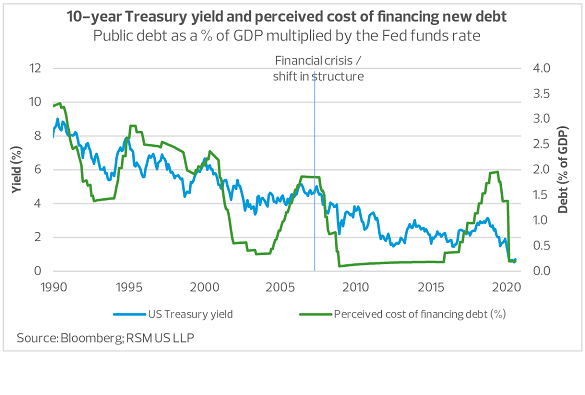

The second shift in structure occurred when the world’s central banks were forced to push policy rates to the zero bound during the financial crisis of 2007-09, and then to keep them there in order to facilitate commercial activity during an excruciatingly slow global economic recovery. The economist Lawrence Summers dubbed this period “secular stagnation,” with GDP growth rarely moving above 2% and with commodity prices dropping due to lack of demand (and changes in technology with regard to the oil market). The result has been to push long-term interest rates below 2%.

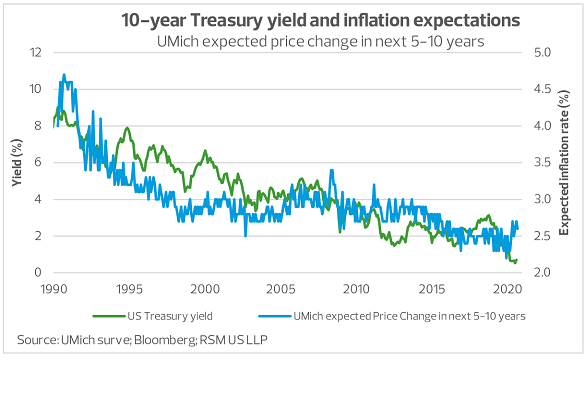

Now, simultaneous threats to global growth from the U.S. trade war and the pandemic have pushed inflation expectations and long-term interest rates tumbling, compressing the yield curve such that 10-year yields are mere basis points above short-term rates.

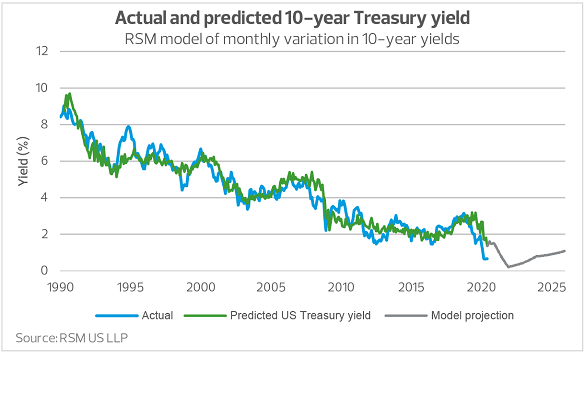

So we find ourselves in a post-inflation world, attempting to project the trend in interest rates that have nowhere to go but sideways or up. (Unless, of course, the economy was to reach the point where the Federal Reserve adopts the negative interest rate policies of the European Central Bank or the Bank of Japan.)

Where do we go from here? Let’s start with some interest rate basics.

Decomposition of interest rates

Long-term interest rates can be viewed as the present value of, first, expectations for the path of short-term rates over the life of the bond; and second, a risk premium to account for events that might cause those short-term rates to deviate from that path. For example, if the overnight interest rate were 3% (at an annualized rate), and you thought that no earth-shattering events would occur over the next 12 months that would affect the rate of inflation, then you would be willing to buy or sell a 12-month bond that was priced to yield a 3% return on your investment.

If you thought that there was a risk of runaway inflation sometime within the next 12 months and that short-term rates would need to be hiked, then you might require a higher rate of return on that bond (which would cover the increase in inflation).

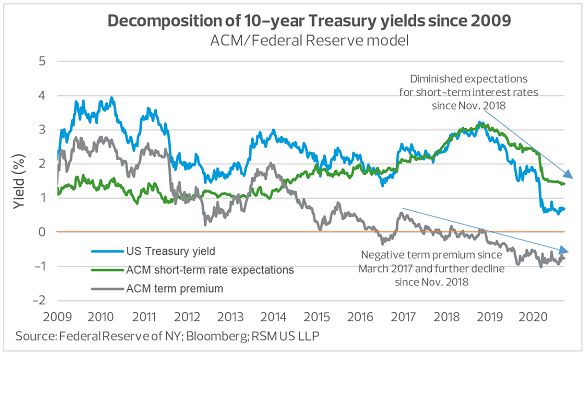

Three economists, Tobias Adrian, Richard K. Crump and Emanuel Moench estimated those two components of interest rates in a paper for the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

As shown in the figure below, the yield on a 10-year bond is the sum of expectations for short-term rates and a risk premium (referred to as the “term premium”) to compensate for potential deviations from that rate over the life of the bond.

It is almost always guaranteed that a catastrophic event will occur over the course of the next 10 years, 20 years or 30 years that will dash all of your expectations. For instance, in just the past two decades, there have been three equity-market crashes to go along with the three recessions, two wars, and one and perhaps two political crises.

At the present, expectations are that short-term rates over the next 10 years will average 1.45%, and that investors will require a risk premium of negative 0.75%, the sum of which results in a yield of 0.7% on a 10-year bond.

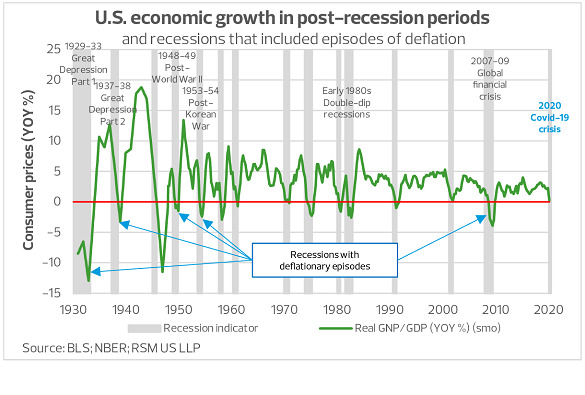

We should note that the negative term premium is the result of apprehension over the prospects for the economy and the risk of deflation. The term premium has been negative since March 2017, in anticipation of the damage to the global economy resulting from the U.S. trade war (and now the pandemic), and the risk that the Fed will be unable to contain deflationary pressures should demand drop to depression-era levels.