Economic fallout from the novel coronavirus pandemic and the civil unrest in the weeks following the tragic death of George Floyd have placed an uneasy spotlight on the disparity in employment opportunities among U.S. ethnic groups—in particular, the wide income gap between white and Black Americans.

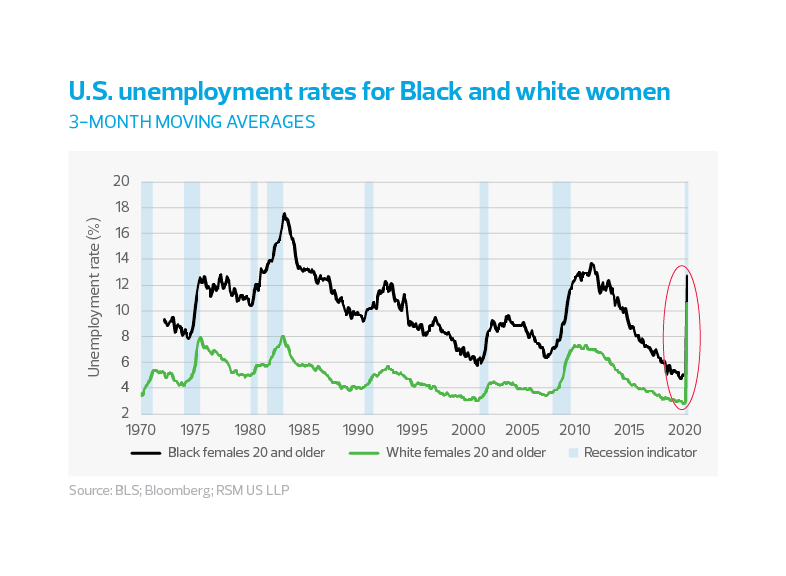

The overall U.S. unemployment rate eased slightly to 13.3% in May, but it is still up sharply from 3.5% in February, prior to COVID-19’s impact; Black Americans during that period saw unemployment increase to an above-average 16.8% from 5.8%. For Black men aged 20 and over, the rate is 15.5%; for Black women, 16.5%.

African Americans, whose ancestors were forced to help build the country’s infrastructure—laying the foundations for free enterprise and the wealth that followed—suffer from systemic racism and the degradation of basic human rights.

Some may point to standouts in the Black community such as Barack Obama and Colin Powell, arguing that everyone has equal opportunity. But this flawed logic is akin to saying everyone has a chance to win mega millions. One must look instead at time-worn systemic patterns to get a handle on the inherent disparities of race.

Why are Americans of African descent victimized by the coronavirus more than those of European ancestry? Why are schools in predominantly Black communities struggling for books and air conditioning, while suburban children in predominantly white neighborhoods attend modern campuses?

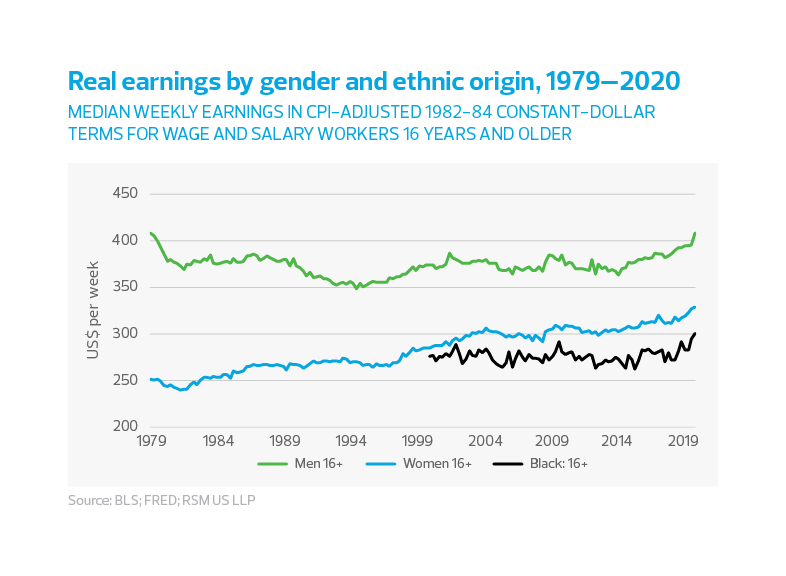

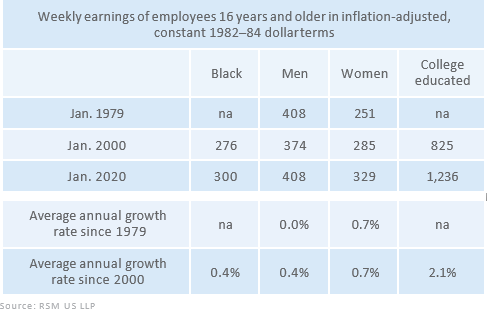

Throughout our history, Blacks in the United States have faced a clearly identifiable employment inequality that persists to this day. With the worst of the economic free fall now behind the United States, the opportunity to address long-term inequities embedded in society and the labor market cannot be missed. Until there is equal opportunity to obtain gainful employment for all Americans, the true promise of America will not be realized.

Using the statistics that follow, you can decide for yourself if the legacy of racism in the United States has been resolved; you will likely see an opportunity to commit to ensuring that equal education, opportunity and well-being become available for all.

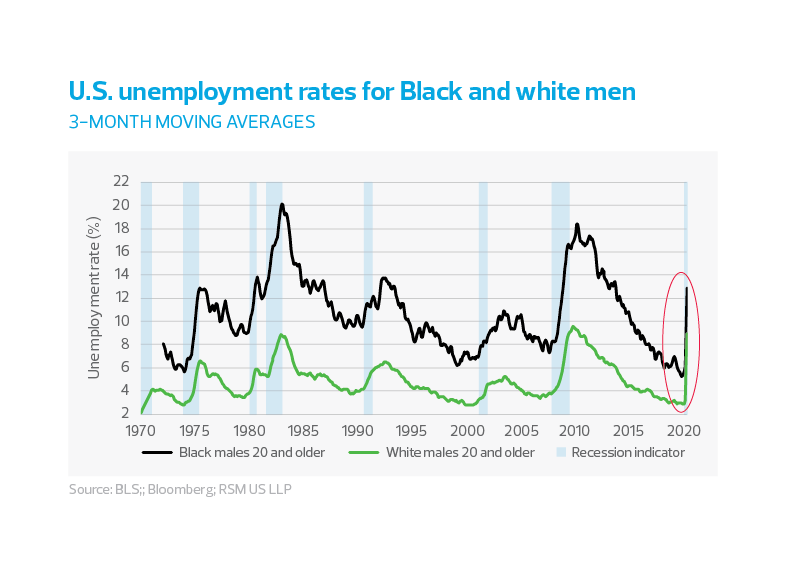

Unemployment rates for Black and white men

Unemployment for white men aged 20 and older has averaged 4.8% since 1972, the earliest year for which data is available. For Black men, it is 10.6% over the same period. Though great reductions in joblessness have been made during the economic recovery since 2010, a gap still exists (see Fig. 1 below).

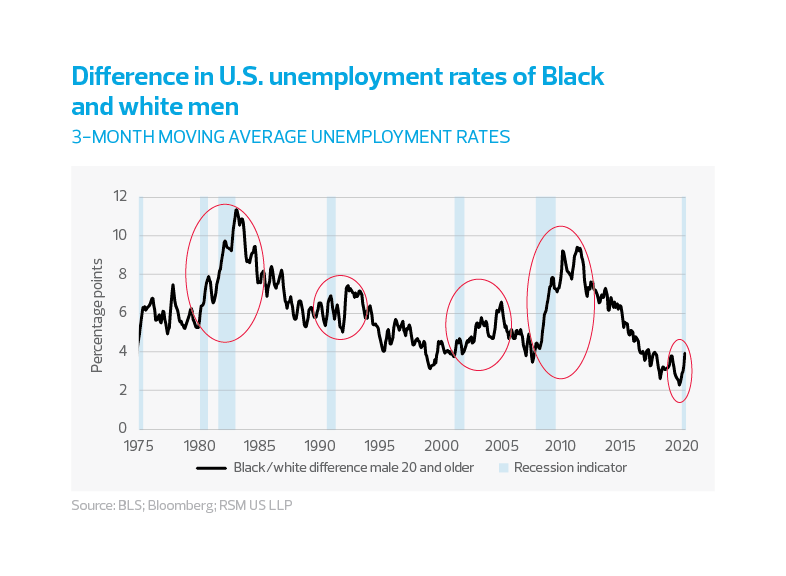

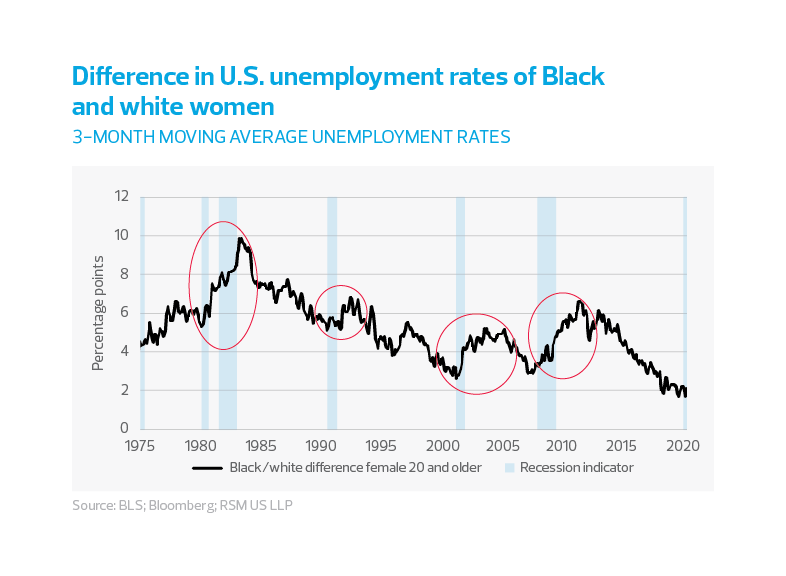

Fig. 2 shows that the gap between Black and white unemployment increases during recessions and then endures for months after, before narrowing again during the ensuing recovery. At best, the pattern speaks to white privilege, but more likely it is evidence of a longstanding bias in hiring and firing.