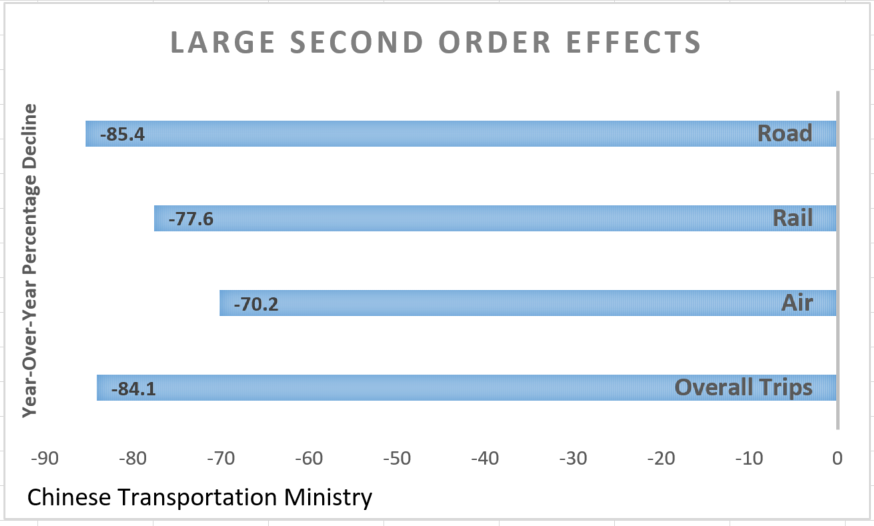

When thinking about the possible economic impact of the coronavirus, it is necessary to first identify how large is the supply shock; and next, what are the second-order effects. Supply shocks tends to be clustered around individuals not working. Second-order effects focus on consumers pulling back from normal spending activity impacting retail, finance, transportation and tourism.

Currently in Beijing, the government is telling citizens returning from the Lunar New Year holiday to work at home until at least Feb. 10. Chinese-based clients and global operators that produce in China report they are shutting down production until the first week of March and postponing scheduled services. Such are the linkages of the globalized economy from which many businesses are connected directly or indirectly through the production of goods, provisions of services, shipping, transportation and finance.

Transmission mechanism

Once one has an idea of the size of the supply shocks, then one must look at channels through which those second-order effects travel, with the most important being trade and finance.

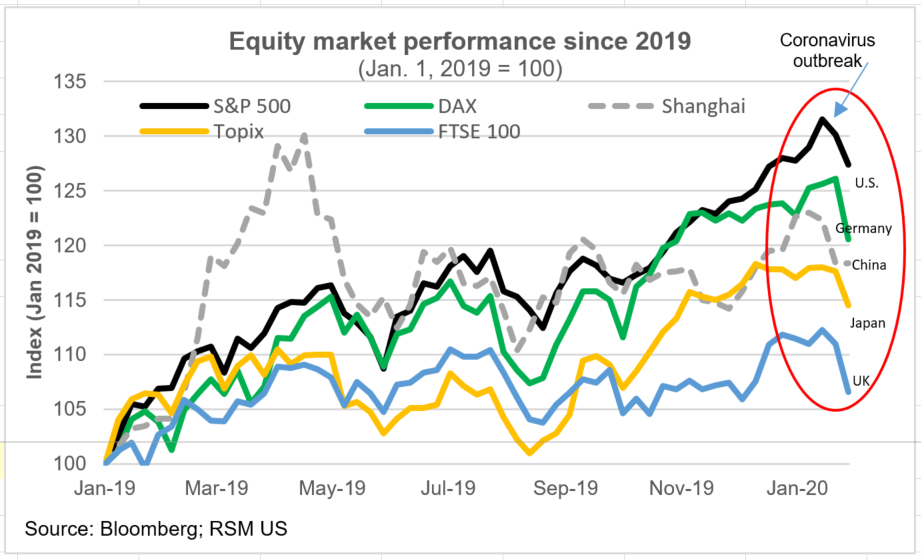

The financial channel waits for no one. The reaction globally over the past two weeks has been swift and fierce, and it shows no sign of abating. The impact has been on vivid display over the past three weeks, most notably in the drop in U.S. yields along the maturity spectrum and the inversion of the policy-sensitive 10-year three-month yield curve often associated with elevated levels of recession risk. The U.S. S&P 500 index has declined by 101 points since hitting an all-time high Jan. 17, 2020, the German DAX has dropped 2% and Hong Kong’s Hang Seng is down 6.6% over the past two weeks. The price of soybeans is down 7.48% and copper prices are off 10%; both are bellwethers of global trade and commercial activity.

The sharp downward movement in prices will place lateral pressure on the implementation of the recent United States-China trade agreement. The drop in soy prices may make it difficult for China to meet the targets embedded in phase one of the pact. The price drop in copper, considered a barometer of demand for housing and commercial construction, surely reflects investor concerns over the pace of demand for commodity imports from China, the world’s largest importer. If this financial channel continues to transmit volatility into and across global asset markets for the next few weeks, investors will begin clamoring for concerted action by global central banks. Right now investors have fully priced in 50 basis points of rate cuts by the Federal Reserve this year, a sign of elevated risk around the economic outlook.

If the financial channel foreshadows a slower period of economic growth ahead, it will be captured in the trade channel. One early forward-looking metric of trade, the Baltic Dry Index—which measures the price to ship raw materials—has declined sharply over the past three weeks, implying there will be a sharp decline in exports to China. Rates for giant capsize shipping used to ship raw materials at earlier stages of production have dropped below $4,000 per day. One would presume the large commodity-exporting economies like Australia and Brazil, as well as the emerging economies in Southeast Asia, will endure most of the adjustment to reduced demand from China. However, that is only a glimpse for forward-looking investors and policymakers of the potential impact via the trade channel. It may be more than a month before hard data reflects the full impact.