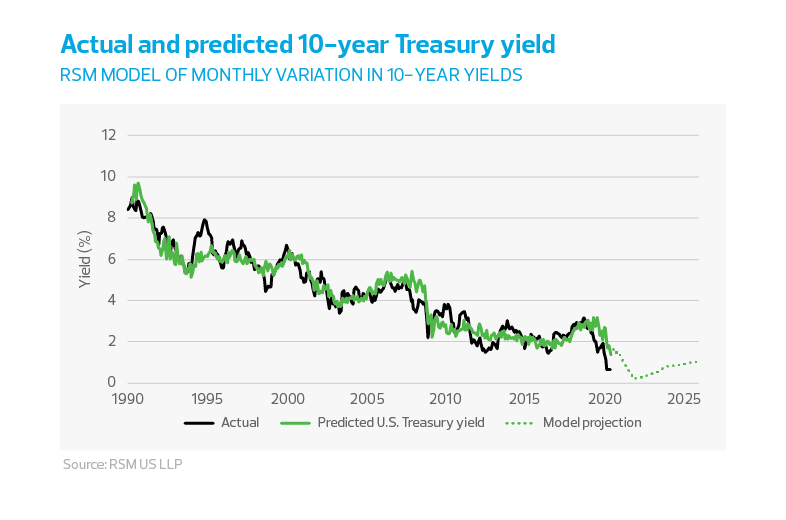

Most significantly, our interest rate models imply that under the current economic conditions, debt accumulation does not provide the outsize risk to the economic outlook through an interest-rate shock, inflation and lower growth than previously thought. For this reason, the United States has the fiscal space to adopt the required policy changes to increase productivity and long-term growth.

Order of operations: Pandemic, vaccine and health care first

Based on our contacts in Washington, we anticipate that the order of operations during the first 100 days of a Biden administration will revolve around addressing the pandemic; development, production and distribution of a vaccine; shoring up the domestic health care system; and modernizing aging infrastructure.

Given that about 10 million Americans have been infected with the novel coronavirus and more than 225,000 have died, it is likely the public will demand action for the production and distribution of a safe vaccine—and for expanded health care in general—during the early days of the administration. We assume this will similarly be the administration’s top priority and that policy efforts will be sustained until the pandemic ends, and the administration can ensure that necessary follow-up health care is put in place.

The Biden health care plan aims to expand the 2010 Affordable Care Act through an increase in subsidies for individual insurance purchases. This would include adding a public option that would directly compete with private health care plans and automatically enrolling some low-income households into the public option. The nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget estimates this would cost roughly $85 billion per year over the next decade. Given the nature and duration of the pandemic, that estimate appears conservative and will most likely undershoot the total costs.

The evolution of public opinion would imply that addressing the pandemic is paramount, and that everything else is secondary. There will almost surely be a move toward a more scientific-based approach to addressing the pandemic and an attempt to rehabilitate the reputation of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Fiscal aid and stimulus

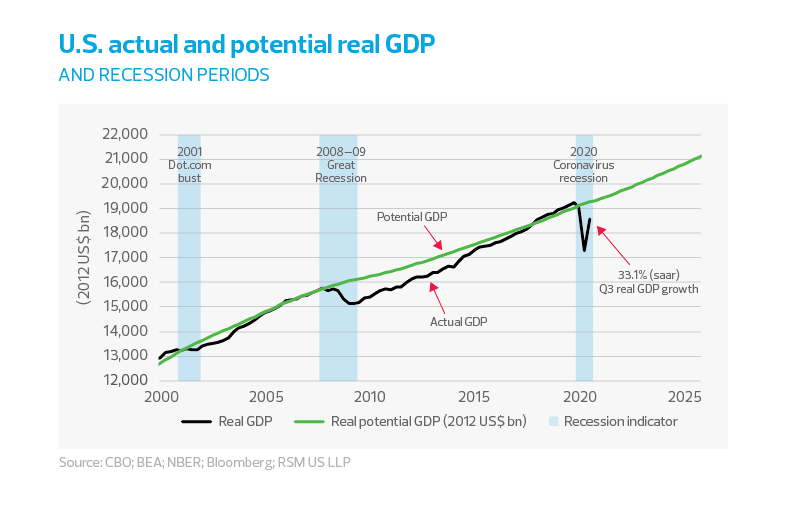

We expect a flurry of spending in the trillions of dollars early in a Biden administration to address the economic impact of the pandemic. The House of Representatives in mid-2020 passed a $3 trillion aid package that was later reduced to $2.4 trillion. Since no further fiscal aid was passed before the election, we now anticipate an initial shot of a further round of $2 trillion in the lame-duck session of Congress or early next year. An opening salvo from the new administration is likely to include additional unemployment insurance and close to $500 billion in aid to state and local governments.

In addition, we expect an additional spate of spending under the guise of Biden’s Build Back Better plan, which would include $300 billion in research and development, $290 billion in Social Security, $1.9 trillion in education, $650 billion in housing and more money to support manufacturing firms and tax credits, all over the next decade.

Economic inequality and the minimum wage

Twenty major metro areas are currently moving toward a $15-per-hour minimum wage, so a Biden administration would most likely move early to address economic inequality. In our estimation, this will not cause any real disruption in hours worked or rising unemployment.

The Democratic platform called for raising the national minimum wage to $15 by 2026, which is more than double the current $7.25 per hour enacted in 2009. Given that the economy remains mired in a pandemic slump and is operating at roughly 80% capacity, any increase in the minimum wage will need to be phased in and tied to overall economic conditions.

Basic economic thought implies that an increase in wages should be predicated on increasing demand and that there is an implied trade-off between an increase in wages and less labor demand or fewer hours worked. But the increase toward $15 per hour during the pre-pandemic economy did not cause a loss of hours worked or lead to rising unemployment. So as the structure of the economy continues to evolve, views on a higher minimum wage are evolving with it.

Rebuilding the future through an infrastructure bank

A prospective Biden administration would most likely turn quickly to address the modernization of the nation’s infrastructure, which in some cases borders on third-world status. Under the Build Back Better program, the administration would put forward $2 trillion over the next decade to address modernization of the economy’s infrastructure, with a particular emphasis on technology. We would label such an approach as I2E, or big I for roads, bridges, ports and waterways, little i for broadband, 5G and other technologies integrated into the national infrastructure, and E for green technologies that would also be a part of the modernization of the nation’s aging infrastructure.

Other than addressing the pandemic, such moves could provide the greatest upside for the administration. A well-executed infrastructure project will yield dividends for years at a time when real interest rates over a 10-year interval are negative. This means that one can repay less than one borrows while reaping medium- to long-term productivity gains, increasing employment and boosting growth.

It would not be surprising if a Biden White House and a Democratic-controlled Congress opt to create an infrastructure bank that utilizes the deep, broad American capital markets to leverage the seed capital put forward by the federal government over the next decade. This represents a tremendous opportunity for middle market firms and could spur legislation benefiting all Americans.

Taxes

It may seem odd that taxes fall so far down on our estimation of the policy priorities of the incoming Biden administration. With the economy still running at roughly 20% below its full capacity, increasing taxes out of the gate is a decidedly suboptimal path. While taxes will certainly rise, what remains uncertain is if those increases are phased in or what any prospective tax reform will look like.

Given the gravity of the pandemic and the long-term damage to the labor market and service sector, the status quo for the American tax landscape seems unlikely to continue. Given the state of the economy, federal relief spending, state budget shortfalls and the unknowns surrounding the pandemic, there will be a need to raise revenue to offset the deficit spending that occurred during the Trump administration and will similarly take place under a Biden administration. For a more in-depth look at the Biden tax plan, please read our RSM Washington national tax team’s take.

The Biden campaign signaled that it would like to restore the top marginal tax rate to 39.6%, up from the current 37%. Exempting 20% of unearned pass-through income would also be on the chopping block, in addition to the reintroduction of a cap on itemized deductions (via the Pease Limitation). Biden has said that he would like to increase revenue by applying a 12.4% Social Security tax (currently capped at incomes up to $137,700) to incomes exceeding $400,000. Businesses, regardless of size or entity type, should evaluate how their current and future operations and cash flow may be affected by Biden’s proposed tax changes.

Trade

The past four years have been characterized by a series of trade wars, and we anticipate that those will cease as the new administration attempts to repair diplomatic and trade relationships across North America, Europe and Asia. This will most likely happen inside a revitalized and renewed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) that encapsulates the trading nations responsible for 40% of global GDP.

With a global trade recovery underway, the trade channel will be a desirable and necessary component of what will be a challenging, yearslong recovery. We may observe a roll back of tariffs put in place during the Trump administration on U.S. trade partners, with the exception of China.

The Democratic platform mentioned China 22 times, and there is something of a bipartisan consensus that Beijing needs to be confronted. It would not be surprising if the entry of the United States into the TPP were framed as a national security concern while other trade concerns were simultaneously set aside in order to economically confront the Chinese and limit their degree of freedom in trade, finance and global economics.

The Trump administration’s approach to addressing China has been to create substantial conflict through administrative action in an effort to wrest concessions from Beijing. The result was a global manufacturing recession; the U.S.-Chinese trade war played a part in pushing the United States into a manufacturing recession this year just before the pandemic.

The forum and location of the conflict may change, but the areas of conflict—theft of intellectual property, currency manipulation and cybertheft—will not fade. Those areas of conflict will most likely pass to multilateral forums where the United States and its trade partners will seek to constrain the Chinese in the coming years. We do not discount the fact that there may be additional areas of conflict over human rights and regional security concerns.

Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve is the single most important economic institution in the global economy. American presidents relish the opportunity to shape the 12-member Federal Open Market Committee that votes on the path and design of monetary policy. Over the next four years, the president will get a chance to replace the chair, vice chair and vice chair for supervision. Additionally, Trump’s nomination of Judy Shelton appears to be stalled in the Senate, leaving a Biden administration with multiple opportunities to put its stamp on the central bank. Given the recent change in the policy framework, we expect a dovish tilt in whoever ascends to the central bank, with bias toward improved employment and the prevention of excess risk-taking in the financial sector.

Expect major change

There is likely to be a period of intense economic reform over the next two years linked to health care, infrastructure and the most robust set of fiscal outlays since the Johnson administration of the mid-1960s—and quite possibly the Roosevelt administration in 1933.

Based on prevailing public opinion, it is difficult to imagine the United States exiting the pandemic without rethinking its health care system or the diminishing lack of opportunity in traditional industrial employment. The economy is quickly moving toward advanced manufacturing and advanced service sector employment. At the same time, an increasingly educated society is fast approaching a racial reckoning, which, alongside economic policies, will form a parallel legislative track addressing civil rights, voter suppression and police reform.