Government spending during the pandemic was unprecedented.

Key takeaways

Now, a different price and rate environment is emerging.

Firm managers and investors should anticipate a significant fiscal narrowing.

Fiscal responses by governments around the world during the pandemic were unprecedented. Many governments spent 20% to 30% of gross domestic product to mitigate the impact of economic shutdowns.

Now, after months of elevated inflation and surging interest rates, a different price and rate environment is emerging.

Policymakers, firm managers and investors should anticipate a significant fiscal narrowing for both public and private actors in the post-pandemic period.

An International Monetary Fund analysis in March of government spending during the health crisis found that “the power and agility of fiscal policy were far beyond what was previously thought possible. Governments channeled cash directly to households and businesses to save jobs and livelihoods.”

Middle market insight

Central banks’ efforts to restore price stability will not only result in fiscal narrowing, but also constrain the ability of governments to use inflation to offset fiscal imbalances.

These actions demonstrated governments’ special role when things go bad, analyst Gita Bhatt wrote.

“But now, the bill is coming due,” she added. “Governments face the tricky task of reducing unprecedented debt to more sustainable levels while ensuring continued support for health systems and the most vulnerable.”

In some respects, central banks’ efforts to restore price stability will not only result in fiscal narrowing, but also constrain the ability of governments to use inflation to offset the impact of large fiscal imbalances.

There is little argument that government spending on vaccines and maintaining income streams during the pandemic saved the global economy from collapse.

Data from the IMF shows the jump in emergency government spending in 2020 being financed by debt. This came as revenue plunged during the economic shutdown.

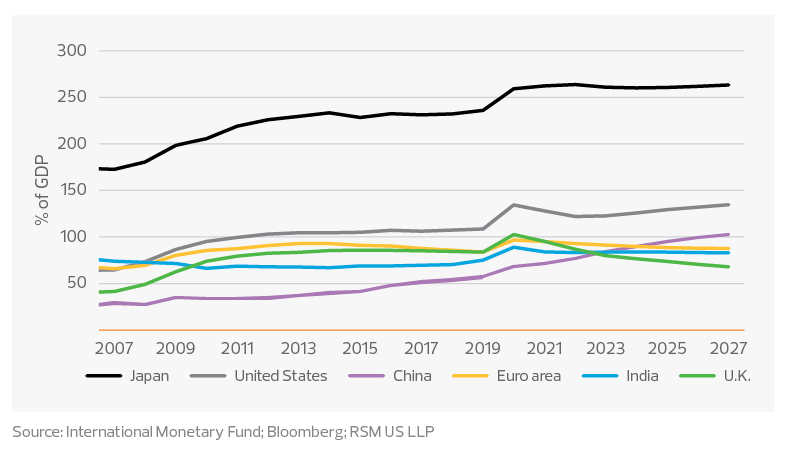

Though the debt relative to GDP in most countries is expected to moderate over the next five years, debt in the United States is expected to increase because of slowing economic activity. And China’s debt accumulation is expected to accelerate, reaching 100% of GDP by 2027.

So has spending gone too far? Are we now paying for it with rising inflation and interest rates that will crimp consumer spending and push the global economy into recession? Has public debt risen to heights that will crowd out private investment and limit growth?

In an IMF discussion on public debt, economist Olivier Blanchard rejected simple fiscal rules and said policymakers must consider the interplay of projected interest rates, economic growth and political stability.

He noted the complications that arise when debt in emerging markets is denominated in foreign currencies, as seen in previous financial crises.

Middle market insight

The U.S. bond market is the dominant force in world finances, and likely to remain that way for the foreseeable future.

Ricardo Reis, an economics professor at the London School of Economics, warned in an IMF article that price stability matters more than ever if debts are to stay sustainable.

The expansion of public debt over the past 20 years was made possible by the decline in inflation and interest rates, he wrote, adding that debt will be sustainable as long as it continues to attract investors.

But as prices accelerate around the world, will we see a run of sovereign debt crises?

In another IMF piece, Emmanuel Saez, an economics professor at the University of California, Berkeley, pointed out that government spending among advanced economies has pivoted from national security basics to providing a social safety net, with public education deemed necessary for economic advancement.

Although spending among emerging economies is increasing, he said it has been insufficient, as evident in the wide disparity of gross income per capita.

We would add to the discussion that the ability to issue debt is an important indicator of the health of the economy.

Japan’s debt has exceeded 100% of its GDP for decades, so there must be a willing audience for that debt. Foreign purchases of U.S. debt subsided during the pandemic as investors sought the safety of cash.

Within those purchases is the implicit guarantee of repayment now threatened by the debate over lifting the U.S. debt ceiling. Forfeiture would worsen the rise in interest rates and deter private investment, hurting growth.

IMF projections of gross debt as a percentage of GDP

How much public debt is too much?

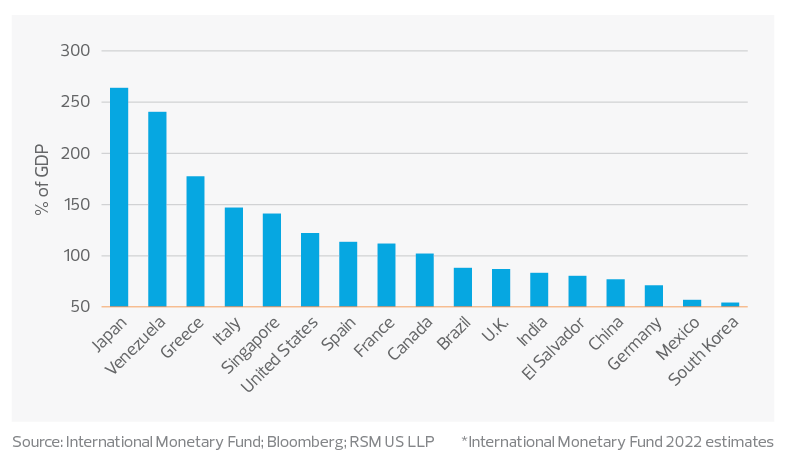

The rule of thumb was that countries with debt-to-GDP ratios of 100% or more were in danger of default—a convenient milestone.

The United States reached 100% in 2012, and Japan long before that, but neither is at the breaking point. So there must be something else that determines when a country has become so profligate that investors lose confidence.

We attribute Japan’s ability to increase debt to its population of savers encouraged by culture and demographics. At worst, the public was willing to finance bridges to nowhere. At best, it accepted a progressive tax policy to finance that debt.

As for the United States, whose taxes have arguably become more regressive with each tax cut, the dominance of the dollar benefits all taxpayers.

In recent decades, the safety of that debt has attracted so-called hot money due to the relatively higher rates of return on dollar-based assets in a world of extremely low interest rates.

Among the economies with debt-to-GDP ratios of less than 100%, the bond market serves as the hall monitor for unfunded, ideologically driven spending, with the United Kingdom and its aborted tax cuts being the most recent example.

Previous debt crises have occurred in Mexico, Latin America and Asia, all inflicting various degrees of damage to financing in the global economy.

Should El Salvador’s experiment with cryptocurrencies backfire, it would be hard to envision the damage spreading beyond its immediate investment and trading partners.

But if confidence in Greece’s ability to repay its loans were to collapse, common sense would suggest a solution exists within the whole of the European community, no matter the eventual cost.

Recent analysis by the IMF found that managing the high debt levels in some countries would become “increasingly difficult if the economic outlook continues to deteriorate and borrowings costs rise further.” The analysis added that if high inflation were to persist, investors would demand a higher inflation premium when lending to governments and the private sector.

Debt-to-GDP ratios of selected economies*

Middle market insight

The U.S. debt has reached what was once an unthinkable height reserved for Japan and less prosperous economies.

Assessing the status of U.S. debt

So with its debt-to-GDP ratio of 122%, where does that leave the United States’ ability to fund that debt and sustain the viability of its financial markets?

Consider these factors:

Confidence in the dollar

The dollar is the vehicle of global trade, with exporters parking the proceeds from sales into U.S. money market securities.

The dollar became the store of value among the world’s currencies in the realignment of global finances at the end of World War II, officially taking over the role held by the British pound.

More than 60% of foreign exchange reserve holdings are in dollars. Euro holdings are now at 20% and have gained traction since the euro’s creation in 1999, particularly because of increased trade with emerging markets in eastern Europe and Africa.

And with most commodities priced in dollars, the transaction demand for dollars remains a dominant force in determining its value.

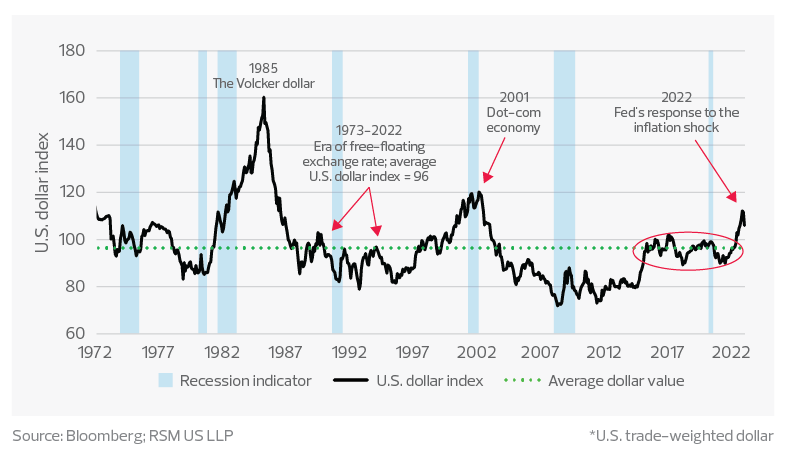

In fact, the demand for the dollar is at its strongest point of the past two decades, rivaling the 1995–2001 surge of demand for dollar-based tech investments. While recent dollar strength is due to investors surging into the higher returns of dollar-based assets, the fundamental strength of the U.S. economy and the safety provided by its securities show no sign of reversing.

Assessing the dollar's value*

Confidence in the Treasury market

The U.S. bond market is the dominant force in world finances.

And because of the U.S. commitment to its framework of laws, regulation of its financial system, and the depth and breadth of its securities, the U.S. bond market is unlikely to lose that status anytime soon.

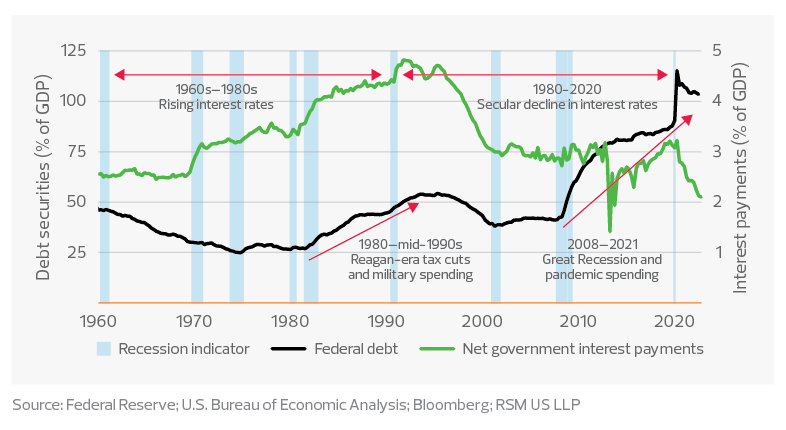

U.S. federal debt doubled from 40% of GDP in 2006 going into the Great Recession to 80% of GDP before the pandemic. Add another 40% onto that during the health crisis and the U.S. debt has reached what was once an unthinkable height reserved for Japan and less prosperous economies.

But interest rates were in decline due to a number of factors—including not only the squashing of inflation by central bankers, but also, more significantly, the decline in energy prices. That led to a decline in net interest payments on government debt.

By the beginning of December 2022, U.S. long-term interest rates had reached 4%, with expectations that inflation would remain higher than the Fed’s 2% target and that interest rates would normalize in the range of 4% to 5%.

In our view, the normalization of U.S. interest rates will not detract from the attractiveness of holding dollar-denominated securities. Rather, because of the increase in global risk, we expect the healthy demand for dollar-based securities to continue.

Federal debt and net interest payments as a percentage of GDP

The U.S. budget

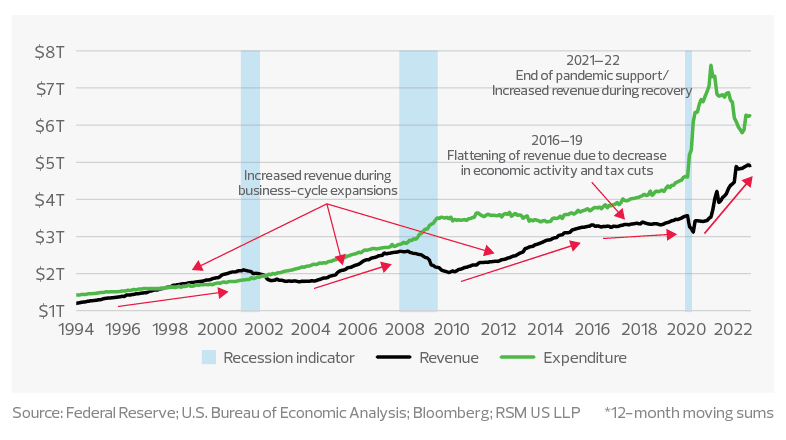

The last time the United States ran a budget surplus was in 2001. Expenditures overwhelmed revenue during the recovery from the Great Recession and then again from 2017 to 2020, that most recent episode being the result of unfunded tax cuts and the drop in revenue because of the U.S.-China trade war.

During the pandemic, expenditures rocketed as government programs subsidized income. Those expenditures have since retreated as those subsidy programs ended.

Fully funded infrastructure spending is scheduled to begin in earnest now that the midterm elections are over, bringing with it expectations of expanded economic activity.

There is little concern that the U.S. economy will falter to the extent that net tax revenue would be insufficient to cover its debt payments. But there are threats from those in Congress who would run the risk of default as a method of shrinking the federal government.

We think that approach is a nonstarter with respect to putting the federal deficit on a path toward sustainability. Given that there is no sizable constituency in Washington or in financial capitals around the world willing to run that risk means we are lapsing back into the status quo that uses the global fixed income market to impose discipline on government spending.

That returns us to the concept of government spending paving the way for economic progress and prosperity, with the bond markets providing the guardrails to ensure sane practices.

Federal revenue and expenditure*