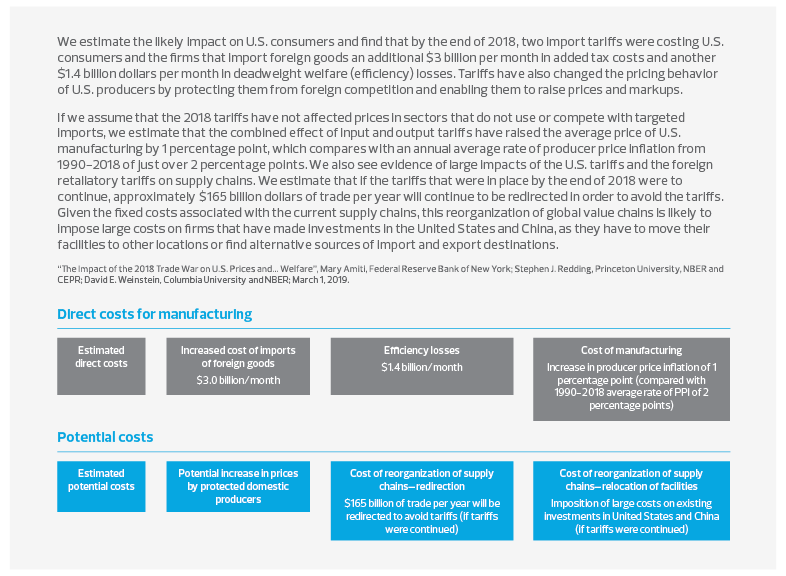

Recent scholarly research has validated concerns about the comprehensive absorption of costs associated with the number of trade disputes in which the United States is now engaged. That research implies that American firms and households are paying a $3 billion-per-month increase in costs caused by trade policy, in addition to absorbing roughly $1.4 billion in welfare losses associated with the policy shift on trade. In addition, if these polices are sustained or expanded, an expected $165 billion in investment will be redirected away from the United States and China, imposing large costs on companies that have constructed related supply chains over the past two generations.

It has become clear that the probability of a near-term deal to roll back the impact of trade conflicts is falling. In May, President Donald Trump increased tariffs on $200 billion worth of Chinese imports to 25 percent. China responded saying it would raise tariffs on $60 billion on U.S. imports. In addition, the White House announced that the administration will shortly release a document containing an additional $300 billion worth of tariff lines on Chinese imports. If the administration follows through on its intent, we anticipate that this would be equivalent to a $137.5 billion tax hike on the commercial sector and domestic households. The United States Trade Representative has planned a public hearing on the issue for June 17. Meanwhile, just last week the administration threatened a series of graduated tariffs against Mexican imports, a move designed to push Mexico to curtail the flow of undocumented immigrants into the United States. Tariffs begin at 5 percent on June 10 and could escalate to 25 percent by October.

Q: Who pays for the tariffs?

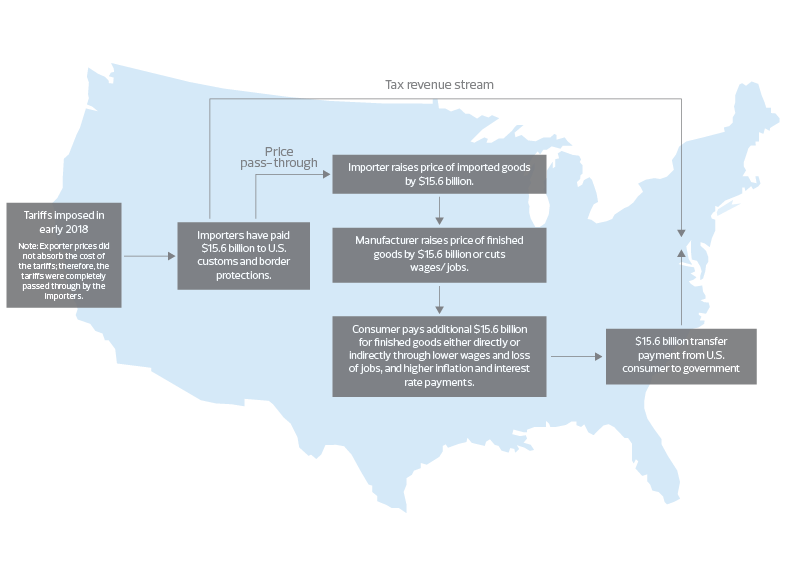

A: There is no evidence that Chinese exporters have absorbed the tariffs by lowering their prices since the imposition of the tariffs.

Therefore, foreign corporations have paid zero; U.S. manufacturers and consumers have paid for tariffs.

Section 232 and auto import tariffs

Since mid-May, the administration can legally announce the use of power under section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 to slap tariffs on imports of all foreign vehicles and auto parts. That represents a possible set of import taxes on an additional $350 billion worth of goods at 25 percent, or roughly $87.5 billion in new taxes on the domestic economy.

Once one accounts for the direct impact outlined above and estimates the indirect impact ensuing symmetrical retaliation from China, at a minimum, there could be an increase of $200 billion to $225 billion in taxes. Should the administration move on these auto import tariffs, then account for retaliation by Japan, the United Kingdom and the European Union, it is possible that during the second half of 2019, the domestic economy will have to absorb $335.8 billion in tax increases. The more benign scenario would include shaving two-tenths of a percent off the gross domestic product in 2019, whereas the expanded trade conflict would shave 0.5 percent. At this time, since we did not assume that the trade spat with China would be resolved, we are holding to our 2019 GDP forecast of 1.8 percent. Should the administration widen the conflict to include the aforementioned economies and industrial ecosystem, we will revise our estimate.

Who pays the costs of protectionist trade policy?

For the past year, we have made the case that the current series of trade conflicts, in which the United States is ensnared, are lose-lose propositions. Our primary concern was the disruption of global supply chains that have been constructed over the past 25 years and the transmission mechanism of financial markets. We now have the numbers to prove it.

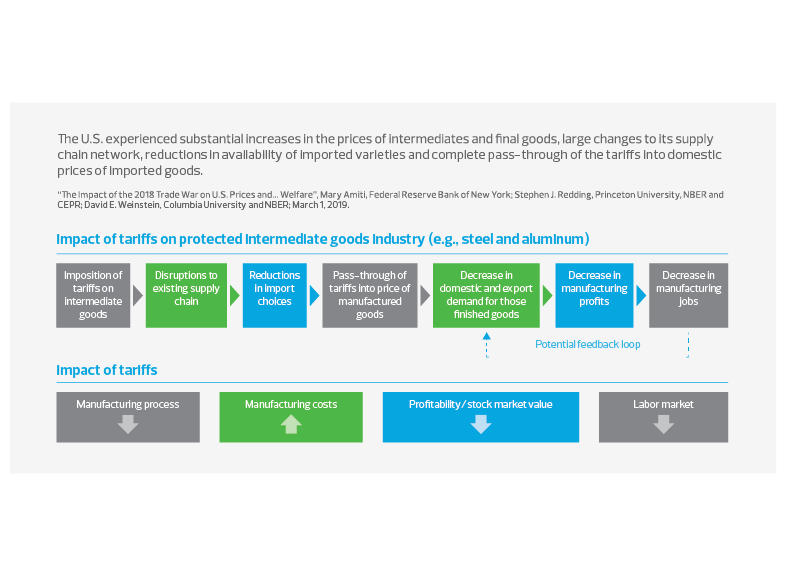

According to a new study published by the Centre for Economic Policy Research, the “U.S. experienced substantial increases in the prices of intermediates and final goods, large changes to its supply chain network, reductions in availability of imported varieties, and complete pass-through of the tariffs into domestic prices of imported goods.” Elasticities and currency volatility did not mitigate the costs for firms and U.S. households. Let us be clear here; a “complete pass-through” indicates that the costs of the tariffs were not absorbed by the exporters through reduced export prices; the Chinese have not borne the direct cost of the tariffs.

Instead, U.S. consumers bear the brunt of the impact in the form of higher product prices, creating a transfer of wealth directly from U.S. consumers to the government. Having absorbed the $75 billion of tariffs collected at the ports of entry in the first three months of 2019, that’s roughly equal to 3.6 percent of all federal revenue taken in during that time. As those tariffs increase, one should expect that tax to affect spending decisions of U.S. households, leading to a slowdown in consumption and reduced economic output and opportunity.

REALITY CHECK: REAL CONSUMER COSTS Consider the case of the import tax on washing machines. A recent Federal Reserve study found that the 2018 imposed tariffs resulted in a 12 percent increase in the price of washers and caused an increase in the cost of dryers. While the federal government collected more revenues from importers, those costs were passed along to consumers; the economic estimate found that consumers paid an additional $1.5 billion via higher prices, or roughly 20 times more than was collected in revenues from higher import taxes.