Ten years ago, the U.S. government sponsored an orderly bankruptcy of General Motors and Chrysler, and their lending arms during the most intense phase of global financial crisis. That bailout—fueled with roughly $80 billion in taxpayer money—forced a sweeping restructuring of the domestic auto industry and set the automakers on a path to profitability that came more quickly than even the most ardent skeptics imagined.

But few could have predicted the challenges that the auto industry faces today. From electrification to autonomous driving and changing consumer tastes, the big three U.S. automakers are grappling with profound change.

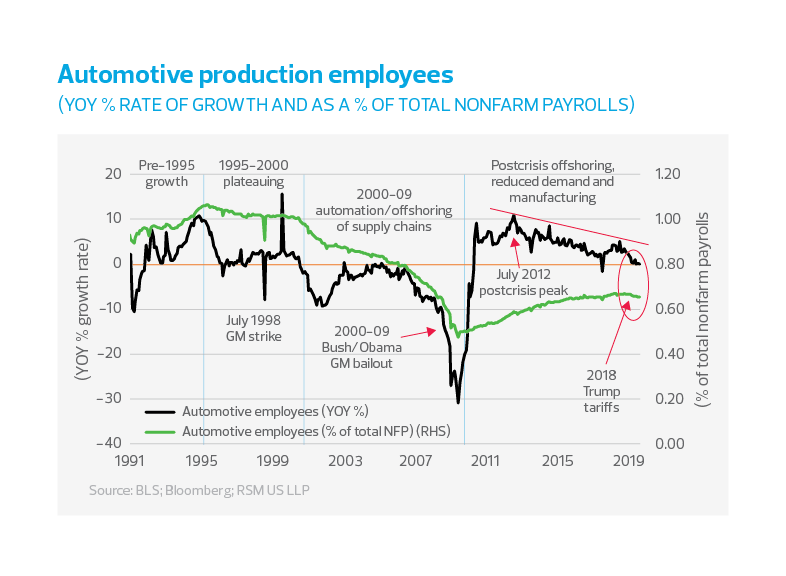

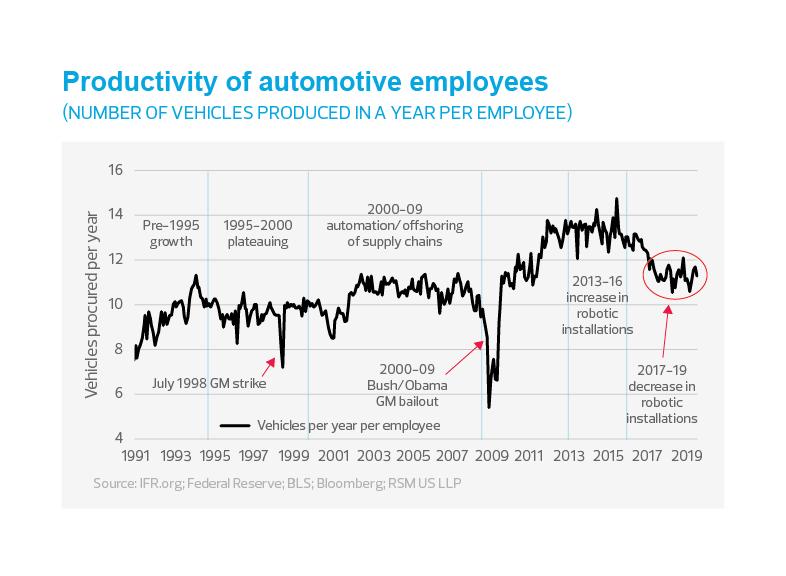

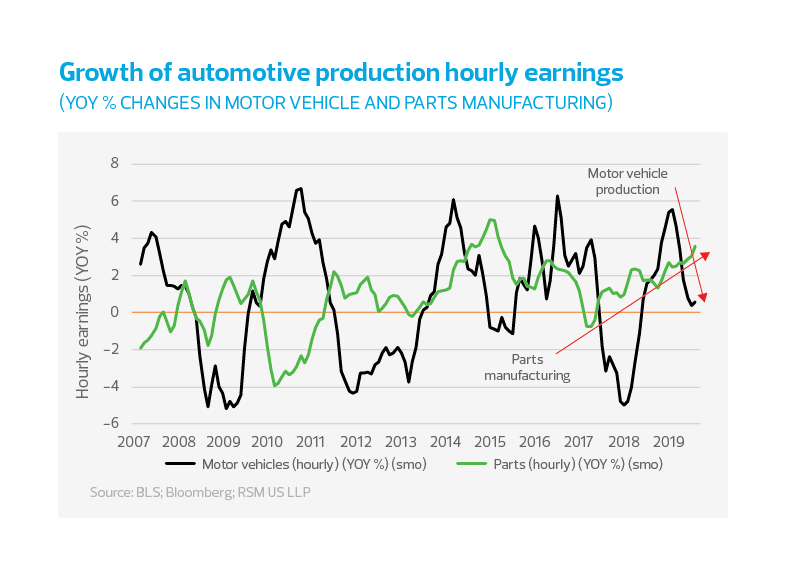

It is clearly time that they move toward consolidation and reshape the industry. But that restructuring will, in turn, hit workers as their share of production declines. Worker dislocation will require a set of policies to cushion the effects of a transformation that will only intensify following the end of the current business cycle.

Most important, the North American and global supply chains built over the past quarter of a century are not likely to be abandoned, and will become even more global, despite the radical shift in U.S. trade policy over the past 18 months. Look no further than China, which has become the biggest producer and consumer of automobiles in the world; the United States is now second. The composition of production will most likely continue to move toward a broader and deeper form of globalization.

That globalization will sometimes favor North American supply chains. Even as General Motors announced that it would close four plants in the United States and one in Canada in 2019, Volkswagen is investing $800 million to make electric vehicles at its plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee. A joint venture between Toyota and Mazda will invest in an assembly plant in Huntsville, Alabama, according to a report from the Wharton School. Ford and VW are about to start a joint venture in producing selfdriving autonomous vehicles for global production.

MIDDLE MARKET INSIGHT U.S. and global middle market firms with exposure to North American and global supply chains should begin preparing for a period of consolidation and dynamic change. The large international auto producers will begin to integrate sophisticated technology into autos amid reduced sales in the wealthy advanced economies.

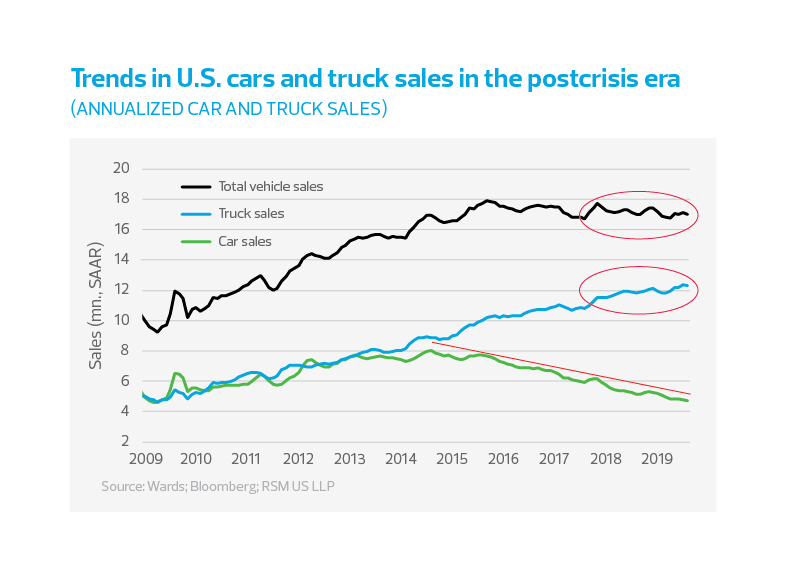

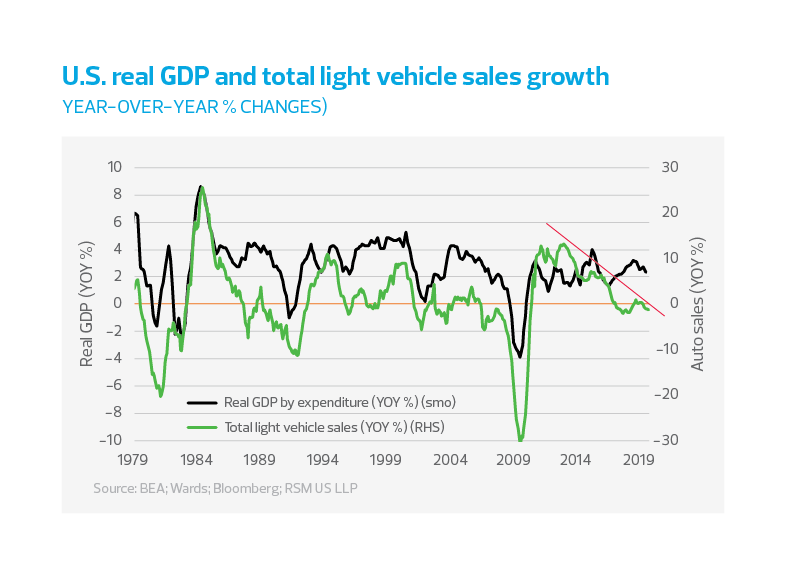

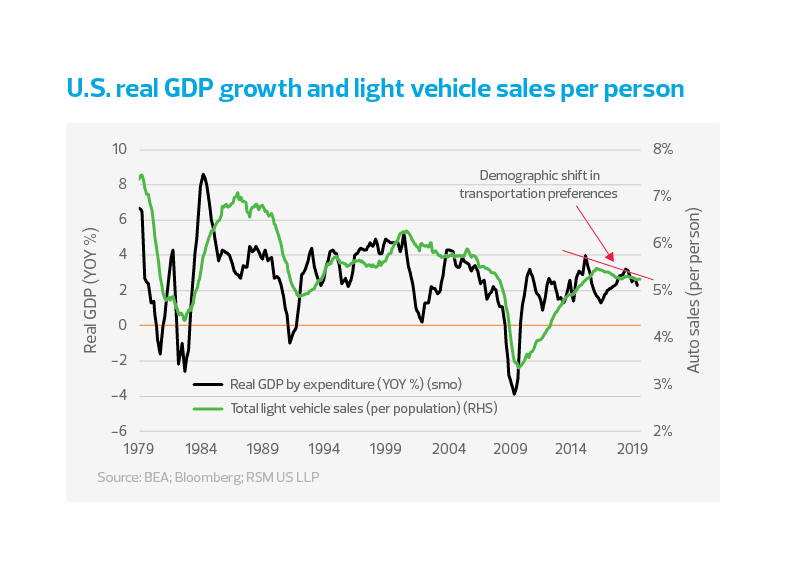

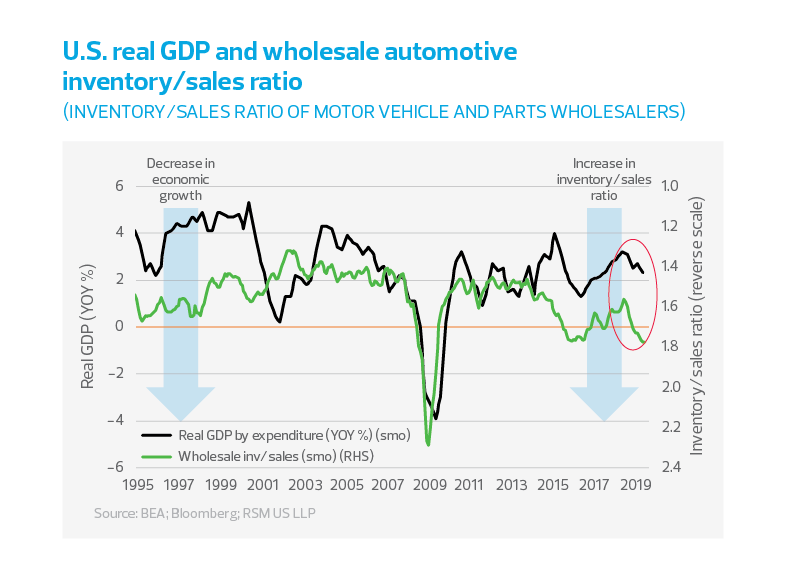

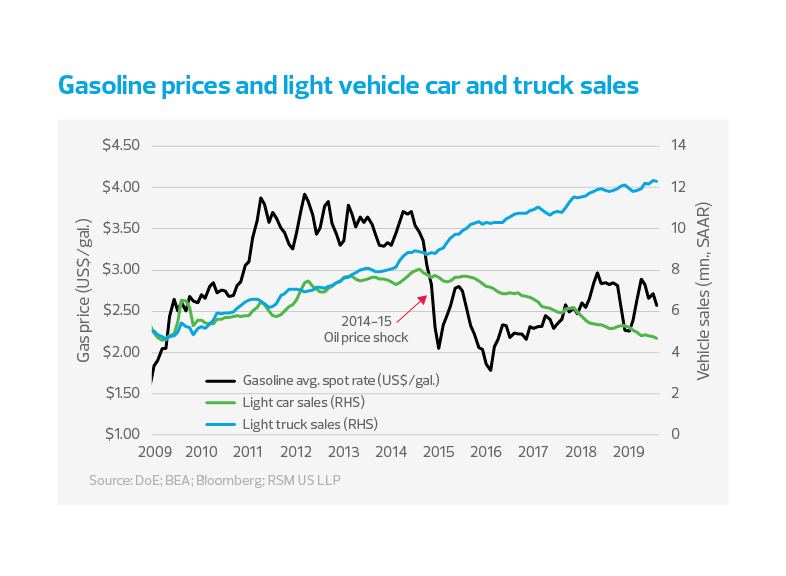

All of this change is coming as automakers grapple with profound shifts in consumer taste, from the type of car to purchase to whether to opt for alternative forms of transportation. Take affordability. As new cars become ever more expensive, many consumers are opting to buy a used vehicle coming off a lease. Edmunds, the auto research firm, reported that the price gap between new and three-year-old used vehicles grew to 62%, or $14,000, in 2018, up from 56% and $11,000 in 2013. And when consumers do buy a new vehicle, they are increasingly favoring light trucks over traditional sedans (see chart), a trend that was pushed along by the 2015 oil price shock. Then there is the question, particularly among millennials and other younger buyers, of whether to own a car at all. For many in this generation who live in cities, it’s cheaper and more convenient to ride-share or opt for public transportation. This trend will continue to reshape the parameters of ownership, consumption and auto production.

Another factor influencing individual car ownership is growing awareness of the social costs of individual, gaspowered transportation. Autos, after all, are a leading cause of polluted air in cities, worldwide climate change and the accompanying health issues.

Automakers are keenly aware of these changing tastes. “We believe the future is electric, and we also believe it is autonomous, connected and shared,” said GM in its sustainability report in 2018. The company’s stated vision calls for zero emissions and it has restructured around this goal.

Ford, meanwhile, announced the electrification of its most popular U.S. product, its 20 mpg F-150 pickup truck. The move seems to sum up the state of the industry—holding onto existing customers and trends, while trying to move forward. It’s easy to be critical of the remaining automobile corporations as being too big to be innovative and too big to fail. But imagine trying to retool the Titanic in the middle of the North Atlantic.

In the end, the challenges of a changing industry leave automakers and their vast network of suppliers scrambling to adapt in a way few could have imagined even a decade ago.