The United States is urging its trade partners to adopt a novel proposal that would put a cap on the price of Russian oil during a time of shortages in global production.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s proposal is a creative idea, but it carries risks and could result in another surge in oil prices. Middle market firms need to understand these risks as they plan for the second half of the year.

The proposal has three objectives:

- Constrain Russia’s ability to finance its war in Ukraine

- Prevent a further energy catastrophe in the European Union and the United Kingdom

- Put downward pressure on global oil markets to help tame surging inflation

To achieve the objectives, the policy would create a purchasing cartel that would limit the price of Russian oil to, say, around $40 per barrel, while not completely cutting off the flow of oil out of Russia.

But that still leaves the question of enforcement—or how to prevent Russia and other nations from getting around the cap.

The answer lies in insurance. The United Kingdom and the European Union insure somewhere between 85% and 90% of Russian oil exports. Together with the United States, they would refuse to permit the insurance of any ship that transports Russian oil priced above the cap.

The U.S. government estimates that oceangoing transport ships move roughly 70% of Russia’s 5.6 million barrels a day of crude exports, with the rest sent through pipelines to Europe and China.

One approach to limiting Russian oil revenues would be to apply significant tariffs. But India or China would resist such tariffs because of the economic damage they would cause. That leaves the price cap, along with the insurance limitation, as the most viable way to limit Russian oil revenues.

Without insurance, it would become almost impossible for Russian oil to be transported. But the approach carries risks:

- The likelihood of cheating. As with all sanctions—and this proposal is essentially a sanction, albeit a creative one—there will be loopholes and cheating, especially given Russia’s sizable share of oil exports. The price difference between our hypothetical $40 cap and the current market price of around $95 per barrel is simply too great.

- The possibility that Russia acts first. Russia may choose to cut off any further oil exports to the world, which would surely send oil surging back toward recent highs near $130 per barrel.

- Distortions to the market. The policy would create further distortions in the global oil market by making it nearly impossible for commercial enterprises to hedge volatility in the market.

- The wild card of China and India. Russia and its largest current consumers—China and India—could simply choose to create an insurance market to cover the risk of transport of Russian oil. At this time, none of those countries appear to have the resources or global trust to create and sustain such a market, but it cannot be discounted.

Supply constraints

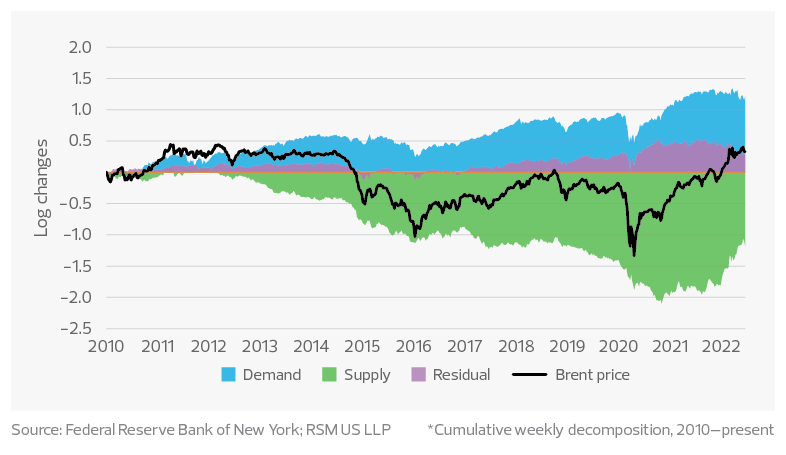

Analysis by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York found that increases in oil prices are currently more a function of anticipation of limited supplies than overwhelming demand. The analysis found that excess supply became a significant driver of oil prices in 2012 and generally dominated price dynamics after 2014.

In the latest period, the analysis found that anticipation of decreased demand in the second quarter of 2022 was offset by expectations of a greater decrease in the supply of oil. By our calculations, that resulted in the futures price of Brent crude oil increasing by 9.5% from March 31 to June 28.