After Congress returned from its summer recess in September, it took little time for the debate over raising the nation’s debt ceiling to escalate.

With the fiscal year ending at the end of September, it soon became clear that the government was heading for another debt ceiling crisis like those in 2011 and 2018.

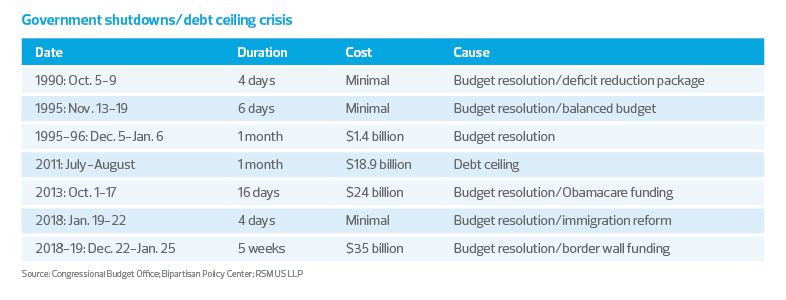

While the causes of those crises differed, the prolonged shutdowns exacted an economic price on the public. A measure to fund the government through Dec. 3 was approved on Sept. 30, but the standoff over raising the debt ceiling remained unresolved. Another politically induced artificial crisis is not in the interest of the economy as it faces uncertainty around the spread of the delta variant.

The debt ceiling is a political artifact that needs to be put to rest. Opportunity will always exist for political actors to create an artificial crisis where there is none. In the past, debt ceiling showdowns have disrupted financial markets, and when the government shuts down, overall growth takes a hit.

The most recent shutdown, in 2018, lasted five weeks and shaved 0.1% of gross domestic product from fourth-quarter growth.

So here we are with another artificial crisis unfolding. Where do we stand?

Don’t push it too far

The U.S. Treasury is taking what it has referred to as “extraordinary measures” to keep the government functioning. The real drop-dead date on a potential default is around Nov. 2. If federal government spending increases because of the pandemic or in the wake of an environmental disaster, that drop-dead date could arrive sooner.

There is always time for both parties in Congress to agree on a continuing resolution, and ample room for compromise like the one that led to the Senate’s recent approval of a national infrastructure package.

But the Democrats do not want to attach a continuing resolution for an increase in the debt ceiling because it would take 60 votes in the Senate to pass and Republicans are on record as being unwilling to cooperate. The risk of a government shutdown on Oct. 1 is rising.

Default is not an option

Put simply, default on U.S. debt is not a reality-based policy option and is a nonstarter. Default is a recipe for chaos across global financial markets and would take the economy back to the depths of the financial crisis in 2008. Individual policy actors who speak of default as an option should not be taken seriously.

Learn from the past

The lessons of past debt ceiling crises and government shutdowns should be heeded.

The 2011 debt ceiling crisis caused a decline in the S&P 500 of roughly 17% between July 22 and Aug. 8 that year, along with a spike at the front end of the curve for Treasury bills as investors sought the safe haven of short-term debt even at the risk of taking losses on their principal.

Short-term U.S. debt with coupon payments around the possible October to November deadlines is currently trading modestly cheaper than other notes. This discount implies that the investment community is beginning to price in a possible debt ceiling crisis at a minimum. Should the specter of a default loom large, as it did back in 2011, short-term debt will be trading far cheaper compared to other notes around the potential Nov. 2 drop-dead date.

Given the risks to the economic outlook linked to the delta variant, this is no time for a politically induced economic event.

In the wake of the 2011 crisis, the Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence Index declined by 31% between July and October of that year, while S&P downgraded the credit rating for the first time in the nation’s history.

The most recent shutdown, in 2018, was because of a budget standoff over funding of a proposed border wall. It lasted five weeks and shaved 0.1% of gross domestic product from fourth-quarter growth that year and 0.3% from first-quarter growth in 2019, or about $7 billion per week from the economy.

Now is not the time

Given the risks to the economic outlook linked to the delta variant, this is no time for a politically induced economic event.

What’s more, with the Federal Reserve signaling it intends to begin paring back its $120 billion per month in asset purchases, a fall debt ceiling crisis would almost certainly result in the pushing of paring operations into next year.