The U.S. bond market is in the midst of a massive sell-off.

Key takeaways

This sell-off is a reaction to persistent inflation and a rapid shift in monetary policy.

The result is the end of an era of low interest rates, easy money and excessive speculation.

The dramatic fiscal and monetary response to the pandemic has elicited a structural break in globalization, growth and liquidity regimes that have driven the world’s economies over the past 25 years.

Gone is the hyper-globalization that was the primary driver of low inflation and low interest rates, and the liquidity that followed.

The higher inflation that has ensued requires higher interest rates and tighter financial conditions to bring it back down, and will lead to what we think will be a recession next year.

As global investors grapple with that structural change, they are driving interest rates higher along the maturity spectrum, causing interest rates to rise.

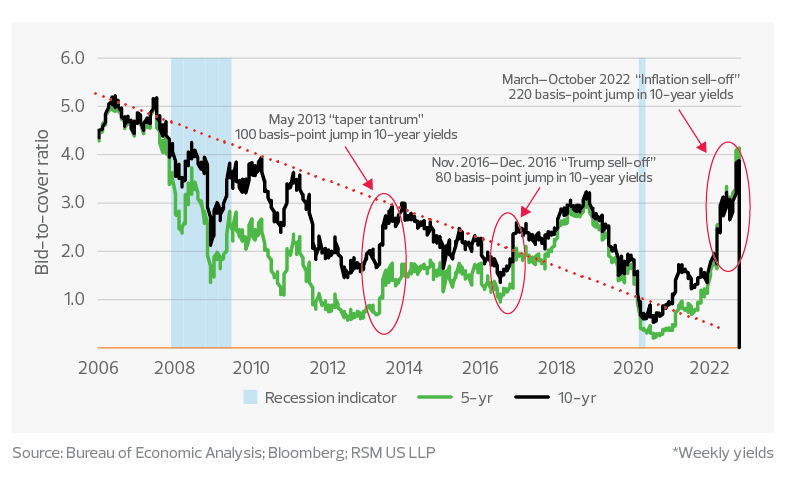

The U.S. bond market is in the midst of a massive sell-off, with 10-year Treasury yields increasing by 220 basis points between March and the second week of October.

This move is the market’s reaction to the prospect of persistent inflation and a rapid shift in monetary policy.

Sell-offs of five-year and 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds*

Yet that 220 basis-point increase is on top of the 120-point increase between July 2020 and this past March.

We can characterize the earlier increase in interest rates as resulting from the resumption of economic activity and the normalization of rates away from the zero bound.

No matter where you place the starting point, anytime you have such a sustained increase in bond yields over such a short period of time, something is bound to break.

The result is the end of a period characterized by accommodative financial conditions, extremely low costs for day-to-day business financing and excessive speculative investment.

For middle market companies, the surging cost of capital will most likely restrain the long-term investments in technological advances that became so apparent over the past two years.

Even though real interest rates, or those adjusted for inflation, will remain negative as long as inflation exceeds 4%, middle market businesses will have a hard time justifying taking on more debt.

This may undermine hard-earned changes in behavior during the pandemic. A majority of middle market firms had indicated over the past seven quarters that they intended to increase investment in capital expenditures, according to the RSM US Middle Market Business Index. But that is now at risk.

This shift is occurring with the backdrop of the worldwide dependence on fossil fuels and the efficiencies of a supply chain that has for decades provided cheap goods and labor to the G-7 economies.

Embedded in that dependence is the inadvertent funding of geopolitical violence and authoritarian rule that runs counter to free market economic systems.

In addition, the lingering effects of a global health crisis continue to disturb the flow of goods and, perhaps more important, distort the labor market.

All these distortions will continue to affect the cost of production and the price of goods and services.

In contrast to other episodes of rapidly increasing interest rates, the recent bond market sell-off appears to be ushering in an economy characterized by insufficient aggregate supply, negative supply shocks, geopolitical tensions and competition between firms and the state for scarce capital.

The jury is still out on whether the bond market sell-off can be attributed to losses in the more speculative equity and cryptocurrency markets and a tightening of financial conditions.

We nevertheless suspect that this sell-off will become what economists call a “shift in structure,” or a substantial increase in interest rates in reaction to the end of disinflation and cheap labor.

A shift in structure

This isn’t the first bond market sell-off, of course. Yet the size of it suggests it has the potential to be something more than the typical sell-off of previous decades.

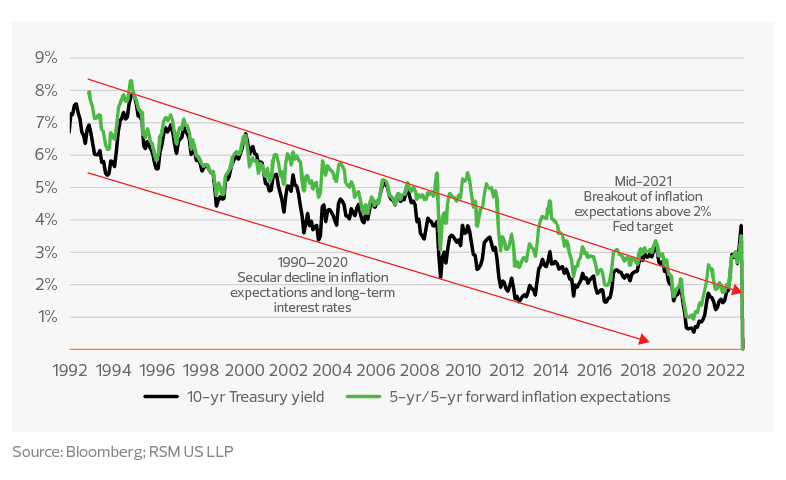

Before the pandemic, the bond market was best characterized as being in “secular decline.” Inflation was being squeezed out of the global economy, a result of the efficiencies of the just-in-time supply chain and the wide availability of cheap labor.

Interest rates were moving lower in economies no longer capable of producing high levels of output that would otherwise support traditional levels of domestic investment or the interest rates to finance that investment.

Because long-term interest rates are determined by expectations of monetary policy and the risk of holding those securities over long periods of time, and because both of those factors are subject to the growth of the economy, 10-year Treasury yields closely followed the ups and downs of inflation expectations.

As a result, the long-term decline in 10-year yields would be interrupted by relatively short-lived uptrends as the bond market reacted to perceived changes in monetary and fiscal policies.

10-year yields and market-based inflation expectations

Our analysis shows the current bond market sell-off breaking the pattern established over the past 30 years. The post-pandemic demand shock and the latest in a long line of oil crises have shaken the climate of price stability to its core.

Inflation expectations broke above the Fed’s 2% target in the spring, and the forward market is now looking for a 3.7% inflation rate in 10 years.

With the conversation even before the inflation shock centered on the Fed having to accept a 3% to 4% inflation target in the medium term, 10-year bond yields have twice exceeded 4% in the past two weeks.

Behind the shift

There are fundamental reasons for what could turn out to be a shift in structure regarding inflation and interest rates.

First and foremost is the schism between the democracies of the G-7—whose prices are determined by market forces—and authoritarian control of fossil fuels.

Second is the structural change within a labor force that no longer accepts the constraints of previous working conditions or wages.

Third is the recognition of the need to diversify the locations of production, which entails the acceptance of industrial policy among Western governments. The latest example is the support for the semiconductor and renewable energy industries. It is highly likely that governments and not firms will drive infrastructure and energy investment, placing upward pressure on interest rates as firms compete with taxpayer-funded entities for scarce capital.

Fourth is the uncertainty over national security threats in Europe and Asia. Increased uncertainty leads investors to demand a higher compensation for holding longer-term securities.

None of these changes will happen overnight. It will take years to fully transition away from fossil fuels and move production back into the developed economies. And the jump in wages is likely to remain a factor in maintaining an adequate supply of labor. All of that is likely to keep upward pressure on the cost of what we buy.

And because of the uncertainty regarding the ability of the monetary and fiscal authorities to minimize the damage to the economy as they fight inflation, we can expect the markets to form new trading patterns at higher levels of risk implied by higher interest rates in the medium term.

State of play

The consequences of the U.S. bond market sell-off are arguably not yet as dramatic as the situation in the United Kingdom, where there is the risk of failure in one sector cascading into others.

Global investors have placed a risk premium on the issuance of government and private debt in the U.K. because of the mismatch between fiscal and monetary policy that resulted in the resignation of Prime Minister Liz Truss.

Even with the end of the Truss government, the upheaval in the bond and equity markets has been concerning.

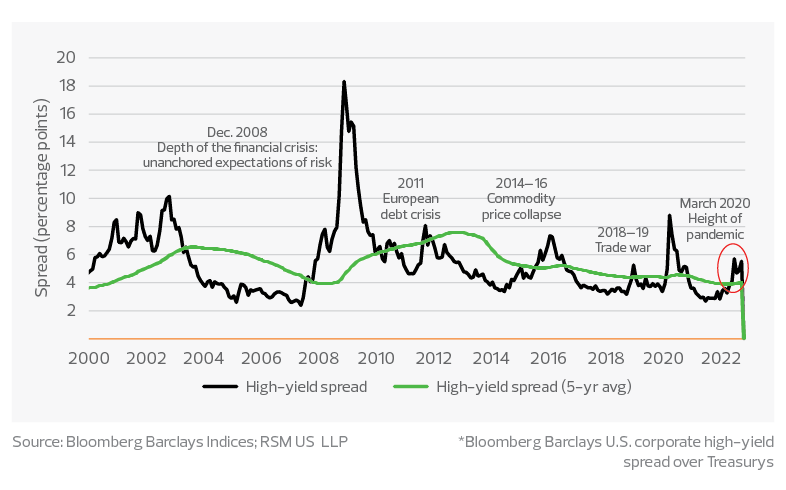

At the corporate level, the increased level of risk is seen in the interest rate spread between high-yield (less than investment-grade) corporate bonds and risk-free Treasury bonds.

As in any market, a sell-off in the bond markets suggests a degree of illiquidity, with an excess of supply meeting reduced demand.

Think of it in terms of the housing market. If a neighborhood becomes less desirable, then the number of willing buyers shrinks along with the price.

Let’s look at the signals within the U.S. bond market regarding the demand for Treasury securities and the liquidity of the market.

U.S. high-yield bond spread*

Bond market testing limits

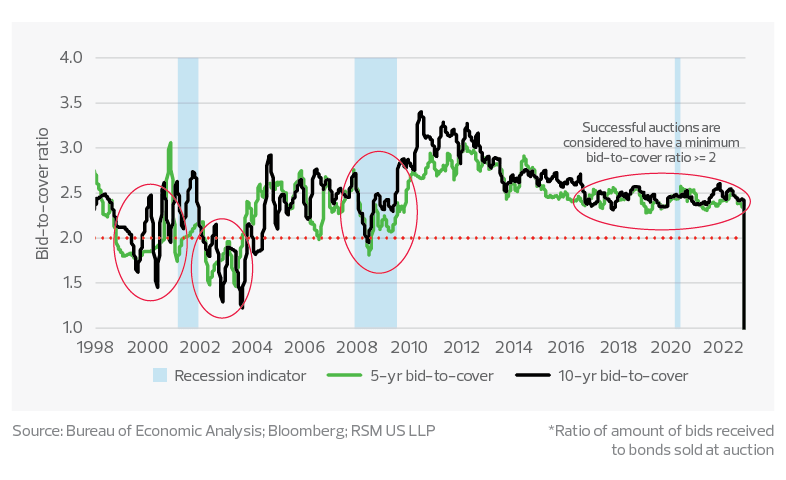

There is still a substantial level of demand evident at Treasury auctions. That can be attributed to obligations by investment funds and the safe-haven demand by long-term investors seeking refuge from the losses and volatility of the equity market.

Despite the inevitable rhetoric about the value of the dollar or the government simply printing money, there is little evidence to suggest a loss of confidence in the ability of the economy to support investment in its infrastructure or in the well-being of its population.

For the past six years, the bid-to-cover ratio for 5-year and 10-year Treasury bonds has mean-reverted to around 2.5 bids received per bond sold at monthly auctions.

Since May, the ratio has moved slightly below 2.5, which suggests a modest deceleration in a still-robust level of demand for Treasury bonds.

This slight drop in demand is small compared to the severe volatility in the bid-to-cover ratio in the run-up to the 2000 dot-com bust and then to the 9/11 attack and the subsequent economic uncertainty.

We can say the same in reference to the decrease in demand during the 2008-09 financial crisis.

Nevertheless, we are left to monitor whether this slight drop in the bid-to-cover ratio of long-term bonds is pointing to an increased preference for cash and a disruption to the bond market.

Bid-to-cover ratio of 5- and 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds*

Bond market liquidity

The Bank of England has recently provided liquidity for pension funds under attack. And during the pandemic, there was a concerted action by central banks to become the lenders of last resort in the money markets, averting a crisis and a collapse of commercial financing.

In terms of liquidity for longer-term securities, the G-7 central banks embarked on bond purchase programs in the wake of the 2008-09 financial crisis, which lowered the cost of capital and increased economic growth. But that’s at odds with the need to increase interest rates to slow spending and stabilize prices.

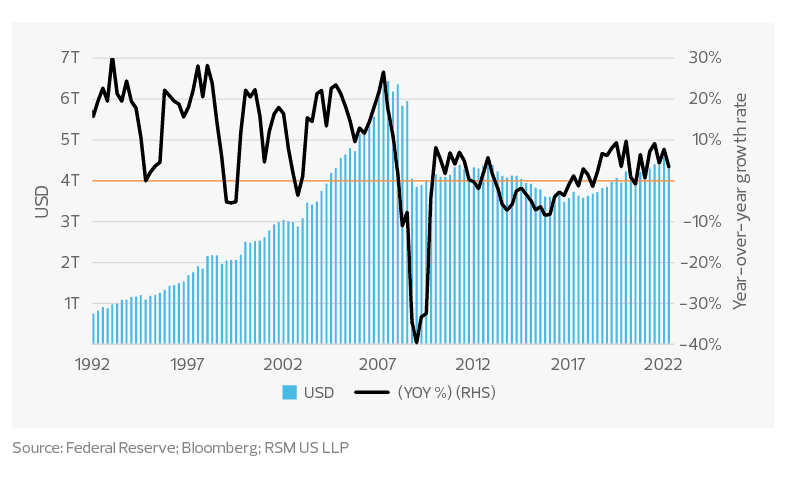

Financial assets of broker-dealers

The tightening of monetary policy has the ripple effect of increasing uncertainty regarding short-term rates.

That increases the risk of holding a long-term security, with investors requiring additional compensation in the form of higher interest rates. The reduction in the willingness to borrow or lend reduces liquidity in the bond market.

The monetary authorities are well aware of the damages to the market and to the health of the economy inherent in the tightening of monetary policy. As reported by Bloomberg, Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen said after a recent speech, “We are worried about a loss of adequate liquidity in the market.”

She noted that the balance-sheet capacity of broker-dealers to engage in market-making in Treasury bonds had not expanded much, while the overall supply of Treasury bills has climbed.

The quarterly flow-of-funds data collected by the Federal Reserve shows that the financial assets of broker-dealers has yet to regain anything near pre-financial crisis levels, with a drop in the second quarter along with a moderation of yearly growth.

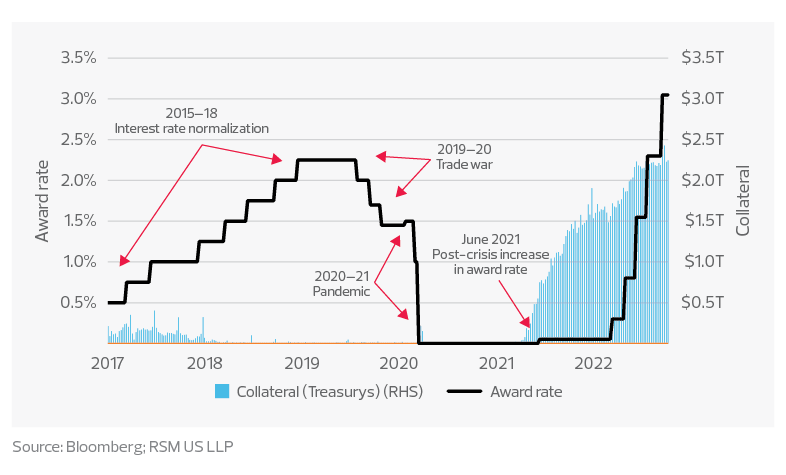

Yellen also noted the presence of the repo facility as providing liquidity in the Treasury markets. Created after the financial crisis, the facility has seen increased usage since last year, and now pays out an award rate of 3% for securities parked there.

We attribute at least some of the success of the facility as a vehicle for parking collateral necessary to short the bond market to the Fed signaling it would begin hiking its policy rate.

In the event of a collapse of liquidity in the Treasury market, we would expect a severe drop in economic activity and another shift in structure that would require a restart of the quantitative easing program and federal funds rate cuts.

Federal Reserve repo and reverse repo operations

The takeaway

The rapid increase in long-term bond yields indicates a higher cost of capital that will affect the willingness of businesses and financial institutions to borrow or lend.

Along with the sell-off in the equity markets, the tightening of financial conditions is part of an intentional program to limit spending and reduce inflation.

We think this marks a break from the era of disinflation and extremely low interest rates. The Fed is likely to consider a new range of inflation above its 2% target as increases in the costs of energy, food and housing, as well as long-term investment, may prove to be too stubborn.

There are also advantages to consider if interest rates stay above 4%. Higher interest rates offer a significant slice of the population a safe place to park their nest eggs. They also imply normal levels of return on investment within the real economy.

In the end, the changes are prompting a regime shift that was hard to imagine even two years ago.

RSM contributors

More from The Real Economy

The Real Economy

Monthly economic report

A monthly economic report for middle market business leaders.

Industry outlooks

Industry-specific quarterly insights for the middle market.