The withdrawal of bond purchases by central banks is stoking financial instability.

Key takeaways

The problems in the U.K. are the clearest signs of stress in global financial markets.

The strains prompt the possibility of another currency crisis like the one in Asia in 1997.

The liquidity crunch driving the withdrawal of bond purchases by global central banks is creating the conditions of a classic policy quandary that is stoking international financial instability.

The challenge in balancing growth, inflation and financial stability is now being exacerbated by interest rate differentials that are causing the American dollar to soar against major trading currencies.

As central bankers and fiscal authorities seek to balance those three policy objectives, there is a growing possibility that we are walking into another financial crisis.

The problems in the United Kingdom, which are linked to inconsistency between fiscal and monetary policy along with financial instability, are the most trenchant signs of growing problems in global financial markets.

But given the fact that dollar appreciation is driven by differentials in interest rates, growth, energy and the safe-haven move into dollar-denominated assets, we think that the more probable site of global financial instability will be in emerging markets, especially Asia.

With the dollar rising to new heights, the United States is exporting inflation through international oil markets—oil is priced in American dollars—by making dollar-denominated debt that much more expensive.

These factors all prompt a question: Will the soaring dollar result in a replay of the Asian currency crisis of 1997?

We would argue that the answer is probably no. Still, the broad depreciation of the major Asian currencies against the dollar will create collateral damage in the region, most likely resulting in demand for financial assistance from the International Monetary Fund.

In our estimation, the G-7 fiscal and monetary authorities will have to cooperate if they are to avoid even a modest replay of the Asian currency crisis. Absent such cooperation, fissures within the global financial system could spill over into the global real economy.

Already, financial markets are sending signals that the policy quandary needs to be solved quickly.

Consider what has already happened:

- The Japanese yen lost more than 25% of its value versus the dollar through the middle of October, with much of that because of long-term sluggish growth in Japan and its near-zero interest rate policy. The Bank of Japan’s recent intervention to prop up the yen has failed and the yen is now trading above 146 to the dollar, which is where the Bank of Japan has traditionally threatened further intervention into currency markets.

- The euro and British pound each lost nearly 20% of their value through October as the Russia-Ukraine war threatens to turn an energy and inflation crisis into a full-blown recession.

- Other Asian currencies have plunged as well. The Korean won lost 20% of its value versus the dollar through the middle of October, the Philippine peso 15%, the Thai baht 14% and the Indian rupee 11%.

The Singapore dollar is the exception, losing less than 7% versus the dollar as it strengthens against the currencies of other trading partners. But that’s because of its position in the global supply chain and its dependence on imports. In addition, the Monetary Authority of Singapore’s policy tool of choice is management of its exchange rate.

So the strength of the dollar is testing the limits of global financial and economic stability. Yet we need to recognize that there are mitigating circumstances.

Since the Asian currency crisis of the 1990s, the emerging-market economies have not stood still. And the monetary authorities among the developed economies have gained experience with each crisis, developing new tools to stabilize the markets and the economy.

Let’s take a closer look at the risk of another Asian debt crisis.

Local currency bond markets

After the Asian currency crisis, there was a concerted effort to reduce Asia’s reliance on cheap dollar funding, which puts local government finances at risk during episodes of dollar strength.

If funding is in U.S. dollars, then the cost of paying down that debt would increase when the dollar strengthens. Minimizing this currency risk entailed the development of local currency bond markets in Asia and the increased ability to fund in local-currency terms.

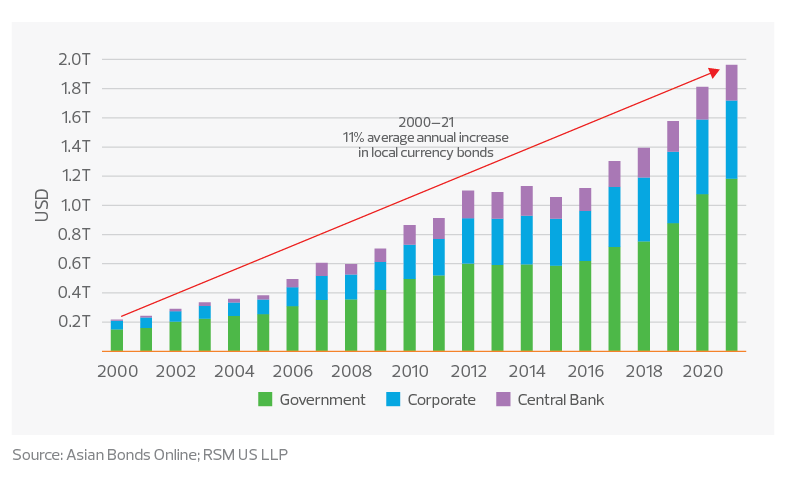

As of last year, local currency bond markets of ASEAN-5—the five major countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations—had grown tenfold, from $200 billion to nearly $2 trillion, according to an analysis by AsianBondsOnline.

While bond market growth of 11% per year is certainly not a panacea for all the world’s troubles, the likelihood of a catalyst for a global recession developing out of insufficiencies in the Asian debt markets has been reduced.

Size and growth of the ASEAN local currency bond markets

Foreign exchange holdings

At the core of the global supply chain has been the stability and financing of the U.S. dollar. The dollar dominates worldwide commercial activity, and in particular the pricing of energy and food. If a country is buying oil or wheat, then it will need to convert its local currency into dollars. If the dollar is soaring, then the cost of the oil and wheat will also soar, hurting the local economy.

Each of the central banks has holdings of currencies of other countries, with those reserves acting as an insurance policy should the value of their domestic currency collapse.

As we saw with the Asian debt crisis, this is particularly important if government debt is payable in dollars and the dollar’s soaring value strains the ability to cover those liabilities.

A study by the Federal Reserve discusses the dominant role of the dollar as a medium of exchange.

About 60% of international and foreign currency liabilities (primarily deposits) and claims (primarily loans) are denominated in U.S. dollars. This share has remained relatively stable since 2000 and is well above that of the euro (about 20%).

It seems obvious, then, that the majority of worldwide reserve holdings would be in U.S. dollars.

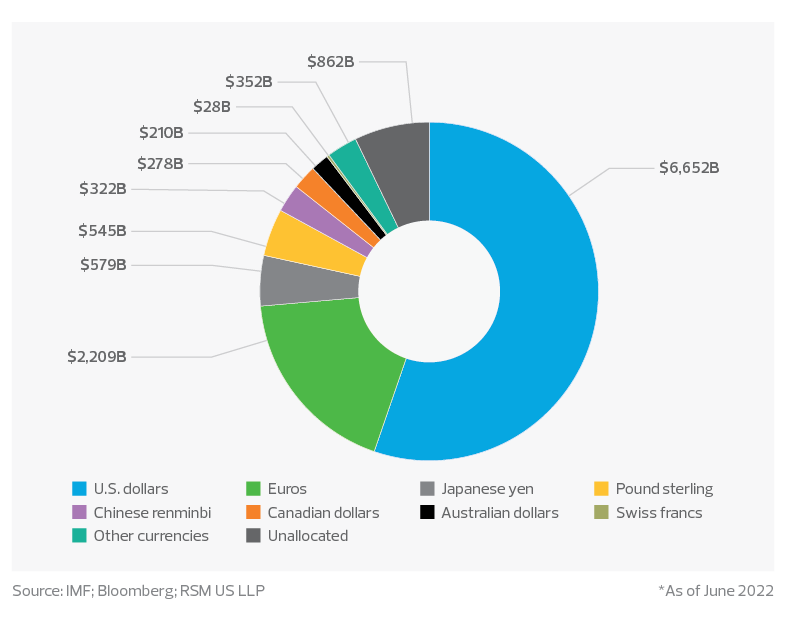

As of June, those dollar reserves totaled nearly $6.7 trillion, comprising nearly 60% of all allocated reserves, according to data from the International Monetary Fund.

Reserve holdings of euros were $2.2 trillion in dollar terms, which is 20% of all allocated reserves.

Among the two remaining major currencies, reserve holdings of Japanese yen were $579 billion and British pound holdings were $545 billion in U.S. dollar terms, with each accounting for 5% of total reserves.

Currency composition of foreign exchange reserves*

The growth and diversification of reserves

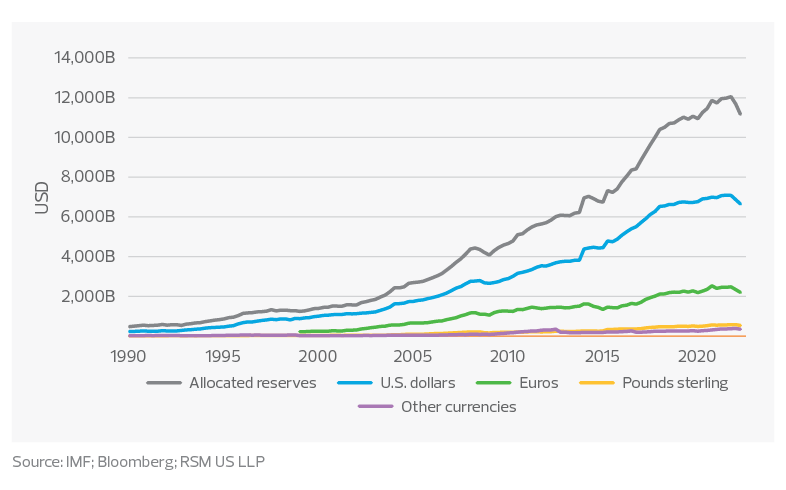

What is encouraging is the growth of currency reserves since 2000. Total allocated reserves have grown at an average pace of 10% per year, with dollar reserves growing at 9.7% per year and euro reserves at 10.2% per year.

And there has been a diversification of holdings. An analysis by the IMF in 2020 noted the decline in reserve holdings of dollars since the euro’s advent in 2000, with the euro becoming the dominant currency vehicle for African economies as well as within Europe.

And we note the increased growth of “other currency” holdings, some of which are approaching holdings of the yen and pound. That may represent what will be a maturation of other economies and further diversification of financial centers.

Foreign exchange reserves by major currency

The takeaway

As in past crises, there is the danger of a financial upheaval in one country spilling over into another.

Just as public health authorities must act swiftly to curb the spread of infection during a health crisis, monetary authorities need to react quickly to the risks of contagion, which can result in lack of liquidity in the financial markets and an economic collapse.

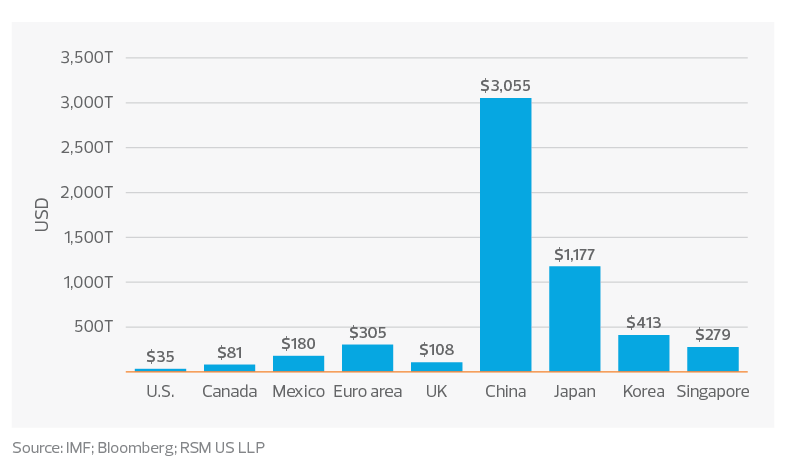

If the currency markets were to come under attack, as they were during the Asian currency crisis, then the monetary authorities would need sufficient foreign currency holdings to cover their liabilities. China is far and away the largest holder of foreign exchange reserves, followed by Japan, Korea and Singapore.

Among the Western economies and those most affected by the cutoff of Russian energy supplies, the euro area has amassed the most reserves, but only a fraction of those held by Asian governments.

If the governments in the West were to conduct currency intervention programs, it would require the cooperation of all the authorities.

Reserve foreign exchange holdings of selected economies

RSM contributors

More from The Real Economy

The Real Economy

Monthly economic report

A monthly economic report for middle market business leaders.

Industry outlooks

Industry-specific quarterly insights for the middle market.