Widespread labor shortages are hampering companies’ ability to capitalize on an economy that is expanding as the country recovers from a devastating pandemic. Companies will not experience a return to the way things were in the labor markets before the pandemic.

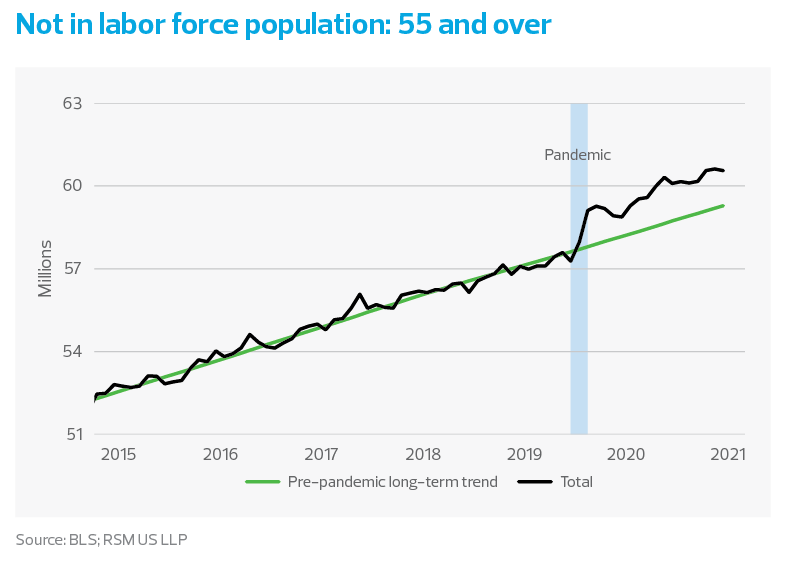

The retirement of baby boomers, lingering challenges associated with the pandemic and a “you only live once” philosophy among many younger workers are driving a structural shift in the labor market away from the conditions that prevailed since the 1980s.

Now employers are wooing workers with improved pay, flexible work arrangements, state-of-the-art technology and better employee treatment. And these changes are just the beginning of what is a significant shift in the American workforce.

Middle market businesses across industries are finding themselves on the challenging end of the labor issue, as they try to ascertain how to navigate the shocks unleashed by the pandemic.

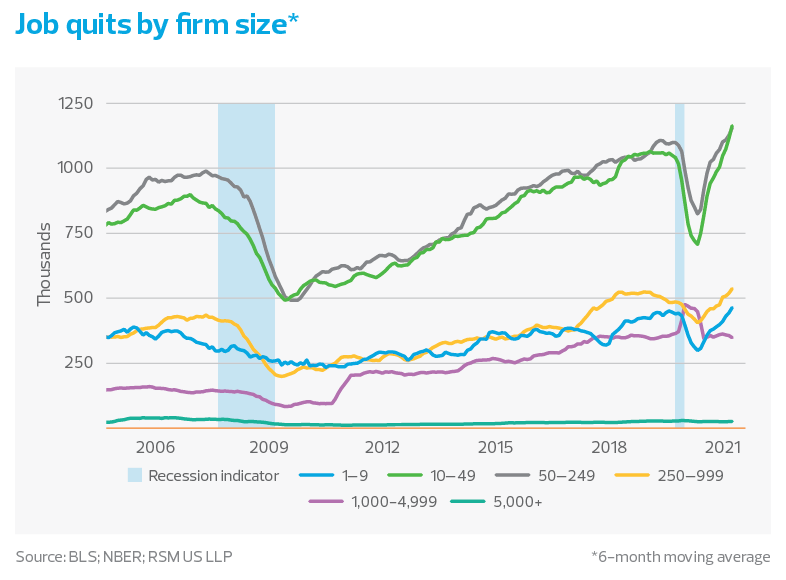

To understand these new dynamics, we have to examine the frictions in the labor market. That starts with the undeniable fact that not only are there not enough workers, but companies are also struggling with high turnover rates and constant employee poaching from competing businesses within market niches and those outside traditional competitive ecosystems.

That dynamic is almost certainly organized around the growing role of technology inside the production of goods and provision of services that is transferring power away from management and to labor.

Although consumer demand and growth remain strong, middle market businesses should always prioritize operating based on the opportunity costs of not taking advantage of such demand and growth. Yet that key requirement also implies something of a radical transformation of those same middle market organizations.

Middle market businesses are finding themselves on the challenging end of the labor issue, as they try to ascertain how to navigate the shocks unleashed by the pandemic.

It is important not to become trapped in the idea that the labor market is simply about supply and demand. The labor market is far more complicated than a commodity market where prices can ultimately drive the final outcomes. Moreover, the premium placed on technological skill sets is transferring a form of bargaining power toward workers.

In many ways, this is the biggest change to the domestic economy since the automotive industry was forced to adapt to more dynamic foreign competition.

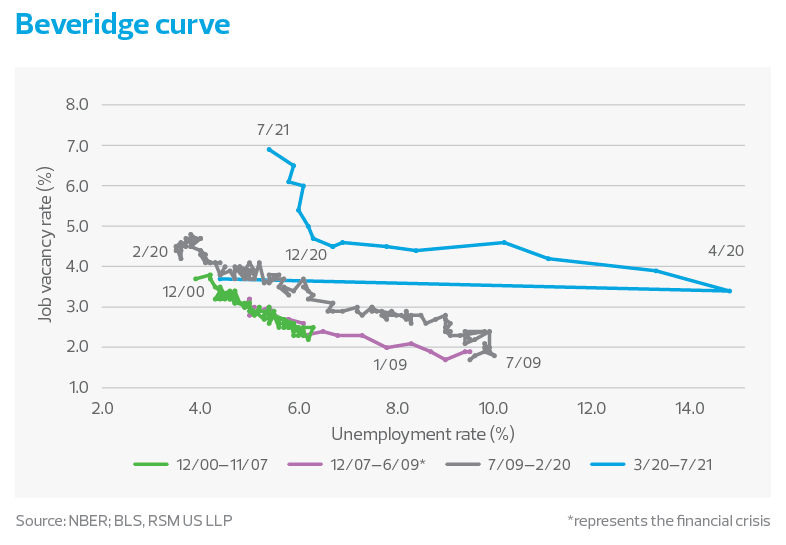

We argue that, on top of a pandemic-related deficit of the labor force, there has been a fundamental change in the structure of the labor market that compensation alone cannot explain. While improved wages are part of the equation to address labor shortages, they are not the sole solution.

This is the first in a series of works that will sketch out what we think will be a transformation of the American workforce that will alter the shape, composition, size and operational framework of the companies that constitute the beating heart and soul of the real economy.

This will be one of the significant managerial challenges of the post-pandemic economy that we expect will redefine the middle market and play a role in the reshaping of the contract between workers and organizations.

It is not about extended unemployment benefits

The pandemic-related unemployment benefits were a substantial addition to existing benefits. In places like Massachusetts and New Jersey, those benefits exceeded $1,000 a week, or about $25 per hour.

As of early September, those benefits had been rolled back in all 50 states as the special $300 per week expired.

So what does the early evidence indicate? The special unemployment benefit did not play a major role in employment decisions by workers. Economists have not shied away from showing robust evidence that extended unemployment benefits can contribute to increasing unemployment durations and reduce job application rates. But it is not a yes-or-no question regarding the impact of extended benefits on unemployment; rather, it is whether the impact is significant or not.

Most studies have shown that the negative effect of unemployment benefits is often small, especially when taking into account the strong positive effect on spending. Recipients of benefits tend to spend most of their unemployment payments, which drives up aggregate demand and in turn, leads to more hiring.

It is important not to become trapped in the idea that the labor market is simply about supply and demand.

A recent study from economists at the University of Chicago focused on pandemic-related unemployment benefits from April 2020 to April 2021. It found that the "disincentive effect of expanded benefits is quantitatively small" and that "unemployment supplements are not the key driver of the job-finding rate through April 2021."

A recent analysis by The Wall Street Journal found that between April and July, payrolls expanded by 1.33% in benefit-cutting states and by 1.37% in benefit-maintaining ones. In a potential labor force in excess of 161 million, there is no significant statistical difference in employment outcomes based on the extension of unemployment benefits.

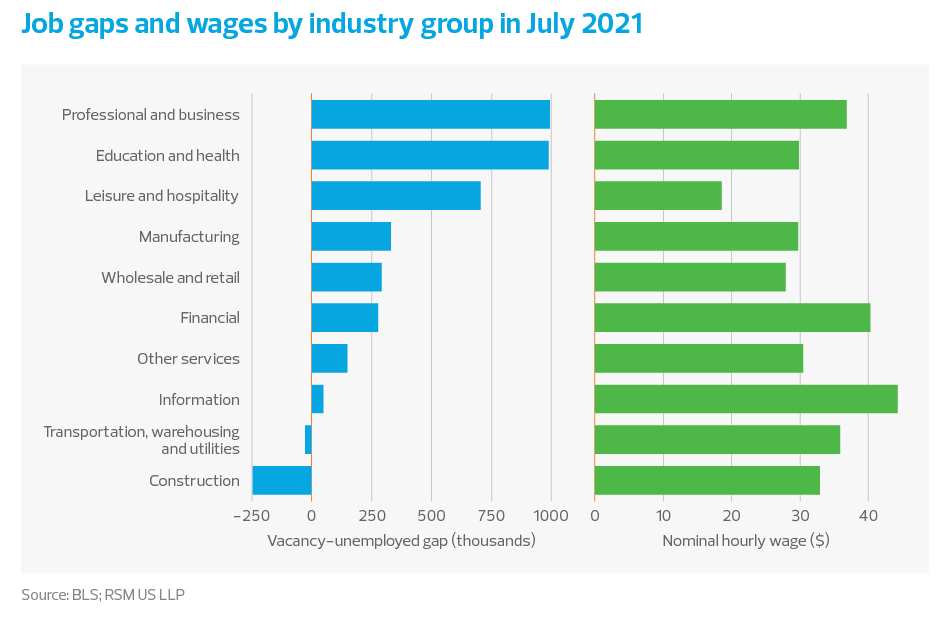

More important, especially for middle market organizations, this fact is also reflected when we look closely at the job vacancy-unemployed gap—which shows the difference between the number of job openings and the number of unemployed workers—by industry group.

The gaps are large not only in leisure and hospitality, and wholesale and retail groups, in which hourly wage rates are the lowest at $18.75 and $27.84, respectively, but also in professional and business services, education and health, and financial services, where the hourly wage rates are significantly higher.

Even if we use the highest unemployment benefit amount from Massachusetts or New Jersey to compare, which is $25 per hour, it is way below the $36.80 hourly wage rate in professional and business services, where the vacancy-unemployed gap ballooned to almost 1 million in July 2021. Any meaningful change in worker behavior around extended unemployment benefits is difficult to find.

Companies should expect that the current labor market frictions will endure past the end of the pandemic and be a persistent feature of the real economy.

Labor force deficit

The lack of labor falls heavily on the simple fact that workers are staying on the sideline and reluctant to return to the labor force. Of course, if one is not in the labor force, he or she is not eligible for unemployment benefits. We need to look at the size of the labor force deficit under current conditions.