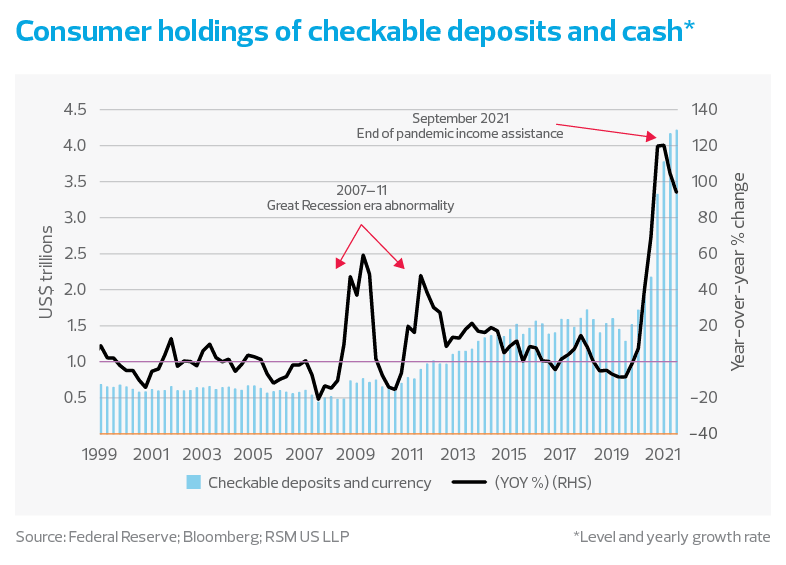

This is not the first time this has happened. Checking deposits surged during the shock of the 2008-09 financial crisis and then again in 2011.

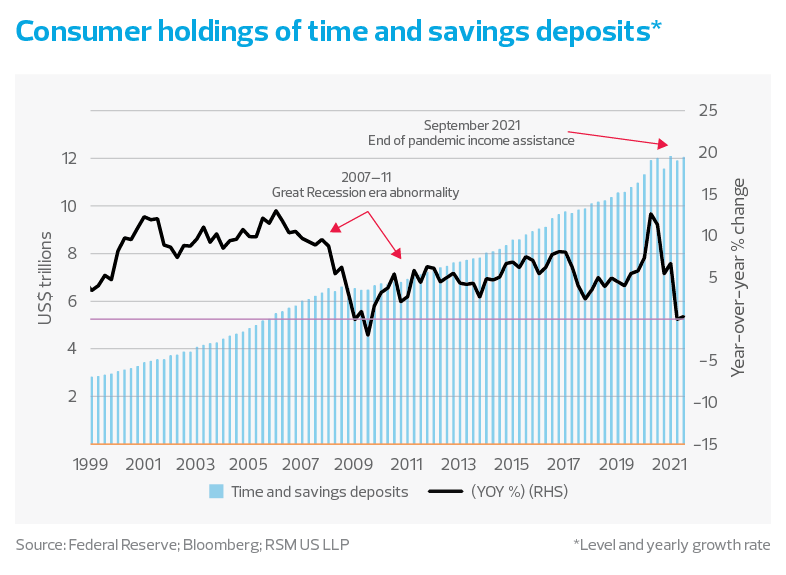

The savings rate, though, was another story. During the 2008-09 recession, savings dropped, most likely as households dipped into their reserves to maintain spending.

But in 2020, savings jumped as government support boosted household balance sheets. Savings has remained at that higher level, not only because of the threat of the pandemic but also because of the limitation of spending opportunities during the pandemic.

In a study conducted by the Institute at JPMorgan Chase in September 2021, researchers found that checking account balances in the lowest quartile of households—those earning $12,000 to $30,000—were 70% higher than two years earlier but were still holding an insufficient cash buffer of only $1,000.

When looking at households that did not receive child tax credit payments, checking balances were 50% higher than two years earlier, but still insufficient at $1,600. For high-income groups, $4,000 checking balances in September were 40% higher than two years earlier.

It makes mathematical sense for low-income households to have the largest percentage change in their cash balances because of pandemic assistance, and for their checkable holdings to be depleted more quickly as reported in the JPMorgan report.

Conversely, the percentage increases for higher-income households during the pandemic were not as large, but their rates of depletion were slower.

In our estimation, that accounts for the persistence of savings still to be spent by higher-income households. It also implies that there is policy space to address the needs of low-income workers who are still dealing with the economic fallout from the pandemic.

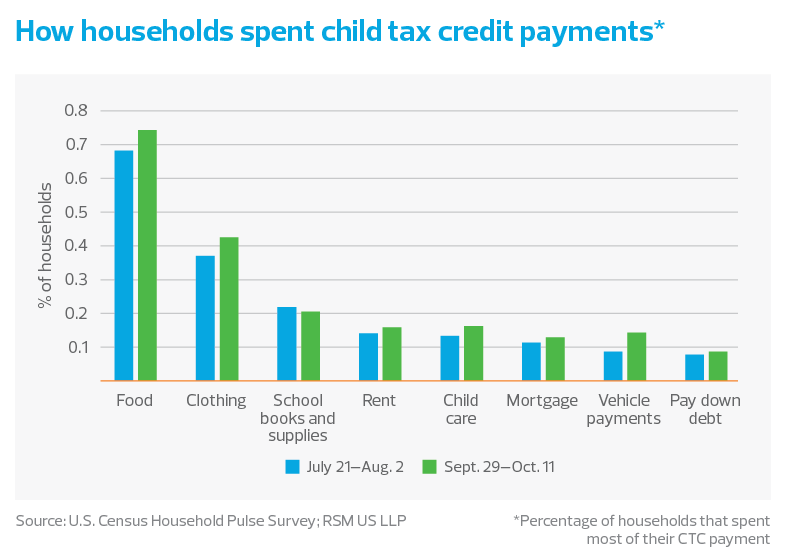

And it also makes sense that lower-income households would apply government benefits for essential expenses. That was borne out of surveys by the Census Bureau in the weeks immediately following the receipt of the first monthly child tax credit payments in the summer of 2021, and then repeated during the fall when the children were back in school.

An overwhelming majority of those who received child tax credits applied those funds to food, clothing and school supplies. Smaller percentages of households allocated a portion of their benefits to rent, child care, vehicle payments and debt repayments.

And as would be expected, 85% of those responding to the survey were 25 to 55 years old, in their prime working age.