48% of respondents said their organizations experienced significant negative effects due to unexpected supply changes.

Key takeaways

Organizations have found other sources of supply both inside and outside of the United States.

Survey responses reveal how 2022 inflation and cost pressures compare to 2018.

More than two years into the global pandemic, supply chain snarls persist for a large portion of middle market American businesses, with smaller midsize firms in many respects bearing a significant amount of the pain, according to proprietary data from RSM US LLP—and companies continue to pivot accordingly.

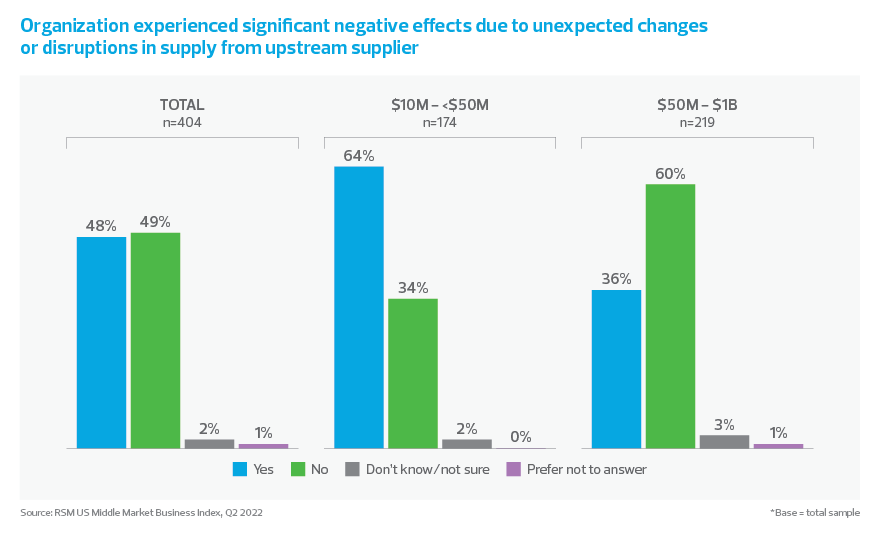

Nearly half of respondents to the latest RSM US Middle Market Business Index survey—48%—said in April that their organizations experienced significant negative effects due to unexpected changes or disruptions in supply from an upstream supplier during the previous 12 months. The survey polled middle market executives from April 4 to April 25 on questions specific to supply chains, as well as questions about costs and inflation.

The data—comprising responses from 404 executives—sheds light on how supply chain disruptions are affecting middle market businesses overall, which issues are having an outsize impact on smaller middle market firms, and the specific ways companies are responding. RSM’s MMBI survey provides a leading measure of the middle market, which accounts for one-third of total U.S. jobs and 40% of the country’s gross domestic product.

The MMBI survey showed a marked difference between smaller middle market organizations and their larger middle market counterparts on this front; among businesses with $10 million to $50 million in annual revenue, 64% reported significant negative effects, compared to 36% for businesses with annual revenue of $50 million to $1 billion.

“We know middle market firms are significantly challenged in attempting to find alternative sourcing where those disruptions are the most severe,” says Joe Brusuelas, RSM US chief economist. “In particular, middle market firms with between $10 million and $50 million in revenue seem to be having the most difficult time adjusting."

Larger companies, on the other hand, have more resources and greater access to capital, which allows them to more easily pivot to another supplier in the face of these challenges, said Dr. Tu Nguyen, RSM Canada economist.

"They can afford to throw money at the problem, essentially,” she says.

The disruption from upstream suppliers had impacts on downstream customers for both the smaller midsize companies and the larger businesses as well. Sixty-eight percent of respondents in the cohort of smaller midsize businesses said unexpected changes or disruptions the upstream supplier organization experienced in turn resulted in negative or adverse consequences for downstream customers; 69% of the respondents from the group of larger businesses said the same.

More competition—upstream

Businesses have grappled with countless supply chain issues since the onset of the pandemic (and for some companies, these challenges surfaced even earlier, stemming from the tariff clash between the United States and China). A key factor at play has been U.S. consumers’ shift from spending money on services—like restaurants, many of which closed their doors either temporarily or for good—to goods, like online shopping and home improvements, amid the pandemic.

“We’re still seeing increased demand for durable goods versus services due to the pandemic, which has continued to exacerbate supply chain challenges,” says Bart Huthwaite, a principal in RSM’s consulting practice.

On top of the already elevated demand pressure, add the war in Ukraine, global port congestion and more recent COVID-19-related factory shutdowns in China, and businesses continue to face a perfect storm of supply chain challenges. The RSM US Supply Chain Index—which provides a near real-time and forward look at the elements of transportation, manufacturing, sales and labor that underscore the manufacturing and service sectors—rose in April but was still 2.51 standard deviations below neutral, the most recent data shows. (An index value of zero—or neutral—is defined as a normal level of supply chain efficiency in RSM’s index, with positive values suggesting adequate levels and negative values indicating deficiencies.)

Middle market firms must ensure they have the right mix of capital and labor to boost productivity

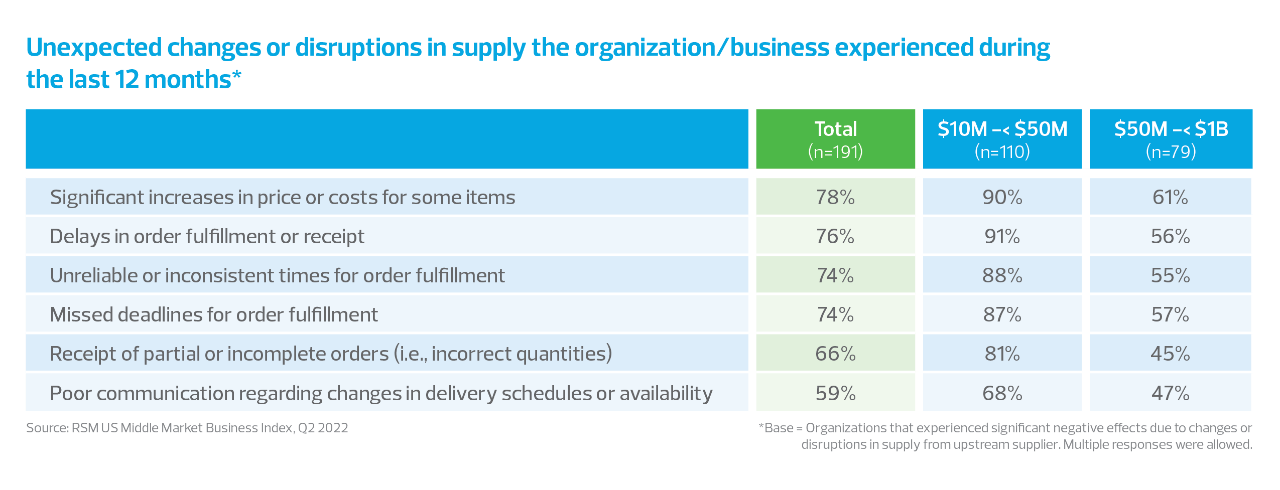

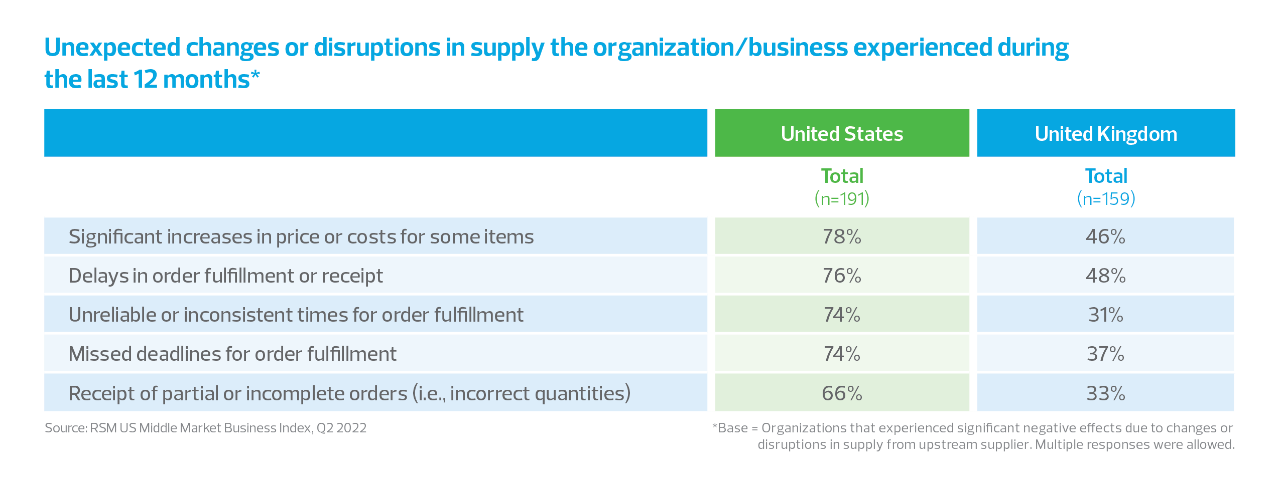

Of the executives whose companies experienced significant negative effects due to disruptions in supply from an upstream supplier over the last 12 months, 78% said they experienced significant increases in prices or costs for some items, RSM’s survey found, with a marked difference by size cohort. For companies with $10 million to $50 million in annual revenue, 90% experienced such increases, and that figure was 61% for the larger organizations.

Looking at both smaller and larger midsize companies combined, 76% of respondents faced delays in order fulfillment or receipt (that figure was 91% of respondents from smaller companies and 56% of those from larger companies), and 74% reported unreliable or inconsistent times for order fulfillment (88% and 55%, respectively).

The fact that significantly fewer respondents from the larger cohort reported issues in those areas might be because larger companies typically have more capital. Therefore, they would have more buying power than smaller companies to get supplies from a given supplier, sending more smaller midsize businesses scrambling to find materials for their products.

“Downstream, smaller companies have always battled for customers,” says Tuan Nguyen, U.S. economist for RSM. But more and more, businesses are also battling for goods from suppliers. “If competitors source from the same upstream companies,” he says, “that means they have to think about the competition both upstream and downstream.”

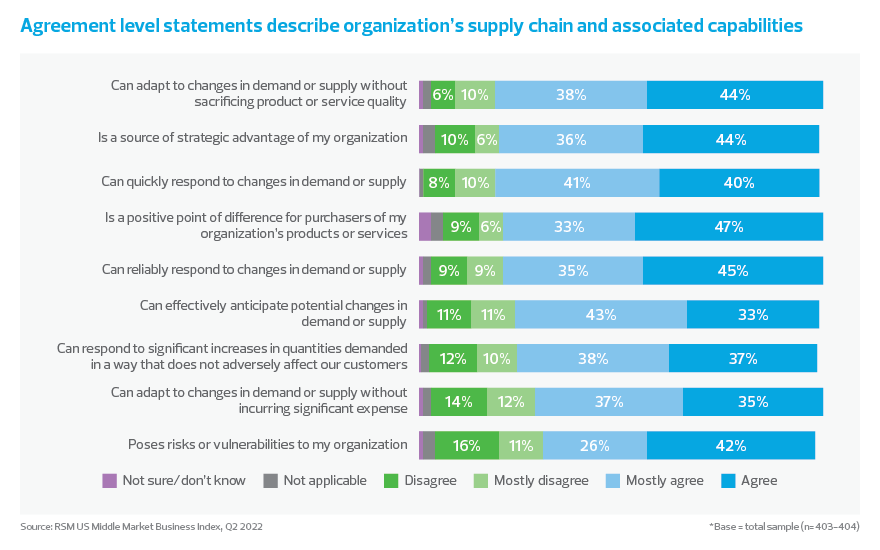

In terms of organizations’ supply chain and associated capabilities, 81% of all 404 respondents agreed or mostly agreed with the statement that they can adapt to changes in demand or supply without sacrificing product or service quality. That figure was 89% for larger organizations versus 71% for smaller organizations. Ninety percent of respondents from the larger-sized cohort agreed or mostly agreed that their supply chain and related capabilities represented strategic advantages for their organization. That figure was 68% in the smaller cohort.

While those numbers might reflect more confidence on the part of larger businesses, smaller ones have other advantages.

“If a firm has the right culture, it can be more nimble and faster to change direction,” says Dr. Tu Nguyen. “You don’t have to go through this chain of command with 20 layers of management approval.”

If a firm has the right culture, it can be more nimble and faster to change direction.

Actions taken and ‘re-globalization’

Companies have taken a variety of approaches to adapt to this flood of supply chain problems, including a closer examination of how well global supply chains serve them. Of companies negatively affected by upstream supply disruptions, 70% said they had found other sources of supply in the United States during the previous 12 months. For organizations in the smaller revenue group, that was 80% versus 55% for the larger revenue cohort. Looking at both groups together, 51% purchased some supplies from competitors at a premium, and 36% found other sources of supply outside of the United States.

While some U.S. businesses may buy less from suppliers outside the country, that will only be sustainable depending on the industry, says Tuan Nguyen. Because of this, the United States won’t likely see a widespread “reshoring” of entire supply chains. Rather, he says, “it's like re-globalization—we’re going to see the rearrangement of globalization.”

“Where there is investment that results in the creation of new supply chains, it’s likely to be regional and specific,” says Brusuelas.

Actions organizations have taken in the last 12 months as direct result of upstream supply chain issues:

70%

Found other sources of supply in the United States

51%

Purchased some supplies from competitors at a premium

36%

Found other sources of supply outside the United States

Leadership teams need to take a holistic view of all the potential factors—from input prices to labor availability—that play into decisions to move supply chains, says RSM US national manufacturing sector leader Jason Alexander.

“A lot of people might suggest moving operations to a specific country because it’s cheap, but if it doesn’t have individuals with the necessary skill set, that’s a problem,” Alexander says. “If we try to take all the manufacturing out of China tomorrow, there’s not enough capacity in the rest of the world to handle it.”

Thirty-two percent of respondents from organizations negatively affected by disruptions exited one or more product lines, and that figure was 42% for the larger cohort and 25% for the smaller cohort. That aligns with what Huthwaite advises companies to do, which is to double down on the most profitable areas of their business.

“Focus on the things that matter and do them in a better way,” he says. “Identify those slow-moving or obsolete parts or products and remove them.”

It's like re-globalization—we’re going to see the rearrangement of globalization..

Inflation and cost pressures

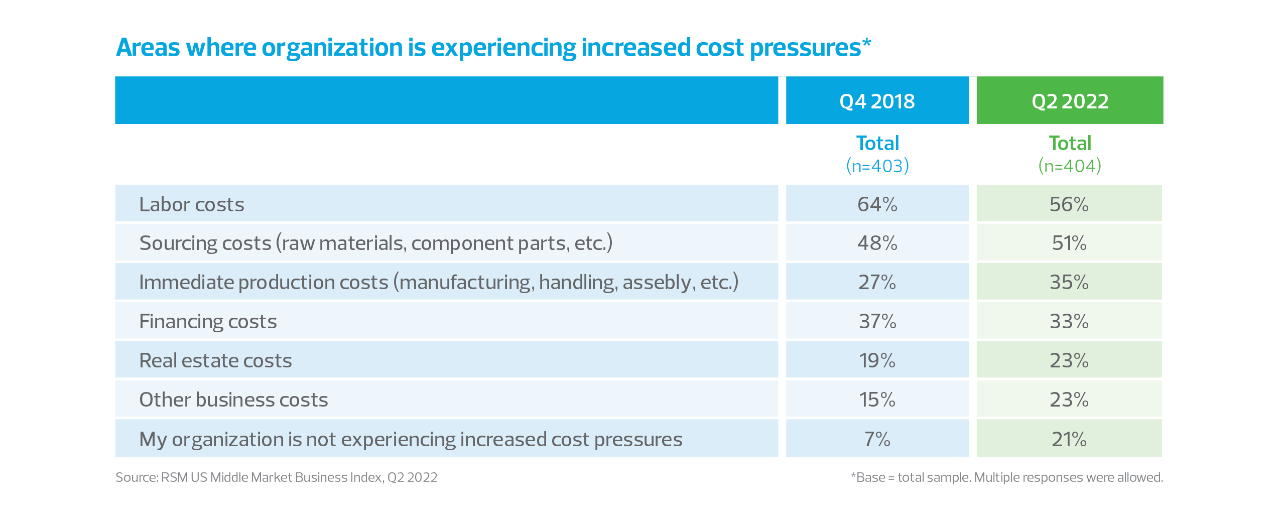

Executives’ responses to the MMBI questions around labor costs, sourcing costs and production costs in the recent April survey varied significantly from those of the fourth quarter of 2018 (when the survey previously asked about this topic), showing greater challenges for smaller midsize companies and some improvement for larger businesses.

Fifty-six percent of respondents said they were experiencing increased labor cost pressures in 2022, down from 64% in 2018—but that figure went up among respondents from smaller midsize businesses (from 69% in 2018 to 78% earlier this year, and down significantly for businesses in the larger-sized cohort (from 61% to 38%). In terms of sourcing costs, 40% of companies with $10 million to $50 million in revenue experienced increasing cost pressures in 2018, which spiked to 74% this year. However, for businesses with revenue between $50 million and $1 billion, that figure dropped from 60% in 2018 to 33% this year.

The top business problem faced by my organization is the issue of supply chain … Any problem in the supply chain, the whole business has problems.

In this year’s survey, pressures around intermediate production costs—which include manufacturing, handling and assembly—also spiked from 27% in 2018 to 35% across both cohorts combined. The difference between the smaller middle market companies and their larger counterparts on this metric is striking; 24% of organizations with between $10 million and $50 million in revenue experienced an increase in intermediate production cost pressures in 2018, and that number effectively doubled to 49% in April of this year. For the larger cohort, the figure dropped from 32% in 2018 to 26% in 2022. Additionally, fewer organizations across both cohorts combined renegotiated costs and associated pricing terms and conditions with their vendors or suppliers in early 2022 than in 2018.

Given all of this, middle market firms must ensure they have the right mix of capital and labor to boost productivity, says Brusuelas.

Somewhat counterintuitively, there may be at least one upside to inflation at a time when some companies are looking to bring some aspects of their supply chains back to the United States.

“Clearly, the disadvantage of using domestic producers is high prices, higher label costs. But when you see high prices everywhere, that disadvantage disappears," says Tuan Nguyen.

A U.S.-U.K. comparison: Supply chain, costs, war in Ukraine

Businesses in the United Kingdom seemed to fare better than U.S. companies on numerous supply chain challenges, RSM data shows. While 48% of U.S. businesses surveyed said in April that their organizations experienced significant negative effects due to unexpected changes or disruptions in supply from an upstream supplier during the previous 12 months, that figure was 39% of the 412 U.K. companies surveyed.

Of the U.K. executives whose companies experienced significant negative effects due to disruptions in supply from an upstream supplier over the last 12 months, 46% said they experienced significant increases in price or costs for some items—which is significantly lower than the 78% of U.S. executives. Other areas where significantly fewer U.K. respondents reported negative effects were in delays in order fulfillment or receipt, unreliable or inconsistent times for order fulfillment, and missed order fulfillment deadlines.

In terms of actions those negatively affected companies took as a direct result of upstream supply chain issues, figures were comparable in several categories from both geographies; 40% of U.K. respondents said they found other sources of supply outside the United Kingdom, for instance, as compared to 36% of U.S. respondents. Thirty-three percent of U.K. executives said they exited one or more product lines, and 28% brought production in-house for some items previously purchased from suppliers (those figures were 32% and 24% for U.S. companies, respectively).

We’ve gone from carrying half a million in inventory to a million in inventory, and basically, we have two people whose entire jobs are beating the bushes trying to find paper. We just know we need to get as much paper in as we possibly can.

Distinctions, however, showed up in the percentage of respondents who found other sources of supply inside their respective countries (70% for U.S. respondents and 51% of U.K. respondents) and those who purchased some supplies from competitors at a premium (51% for the United States, 38% for the U.K.).

“It would appear that the combined lingering impact of Brexit coupled with the unique properties of pandemic induced supply chain disruptions have created a challenge for U.K. firms in finding alternative sources of supply,” says Brusuelas. “Given the shock to the U.K. economy caused by rising oil and energy prices, this implies an extended period of adjustment lies ahead for U.K. firms.”

On the cost and inflation front, 37% of all U.K. respondents reported increased cost pressures around labor, significantly lower than 56% of U.S. respondents. Sourcing cost pressures were also an issue for more U.S. businesses (51%) than those in the U.K. (33%), and the same goes for intermediate production costs (35% of U.S. respondents said they were experiencing increased cost pressures on this front, compared to 27% in the U.K.). In terms of financing and real estate cost pressures, responses from both groups were comparable.

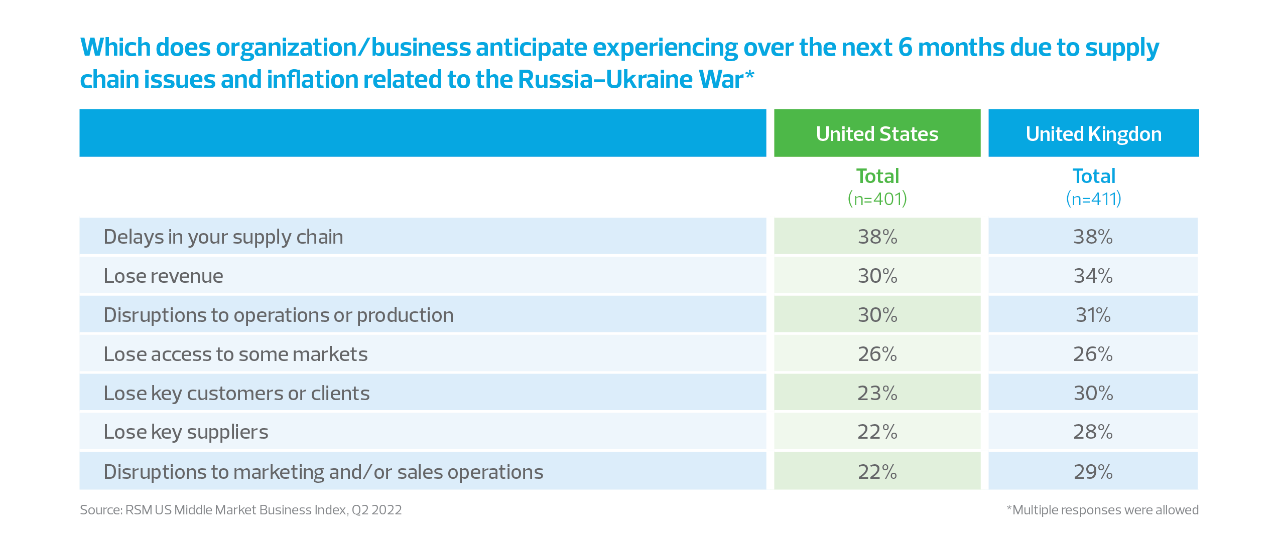

RSM’s April survey also included questions about how organizations anticipate supply chain issues and inflation related to the war in Ukraine will affect their business over the next six months. Effects of the war are already showing up in supply chains for energy, food and other goods.

In both the U.S. and U.K. respondent cohorts, 38% of executives said they anticipate supply chain delays within their respective countries. Twenty-four percent of U.S. respondents anticipated supply chain delays outside their country, with 26% for U.K. respondents. In comparison to their American counterparts, a significantly larger share of U.K. executives said they anticipate disruptions to marketing and/or sales operations, closing one or more worksites, and seeking specialty financing to ensure liquidity.

Download the full report

Related supply chain insights

The Real Economy Blog

The Real Economy Blog was developed to provide timely economic insights about the middle market economy. It is offered as a complement to RSM’s macroeconomic thought leadership, including The Real Economy monthly publication and the proprietary RSM US Middle Market Business Index (MMBI).

The voice of the middle market

Middle market organizations, which make up the “real economy,” are too big to be small and too small to be big. They have distinct challenges and opportunities around resources, labor, technology, innovation, regulation and more.