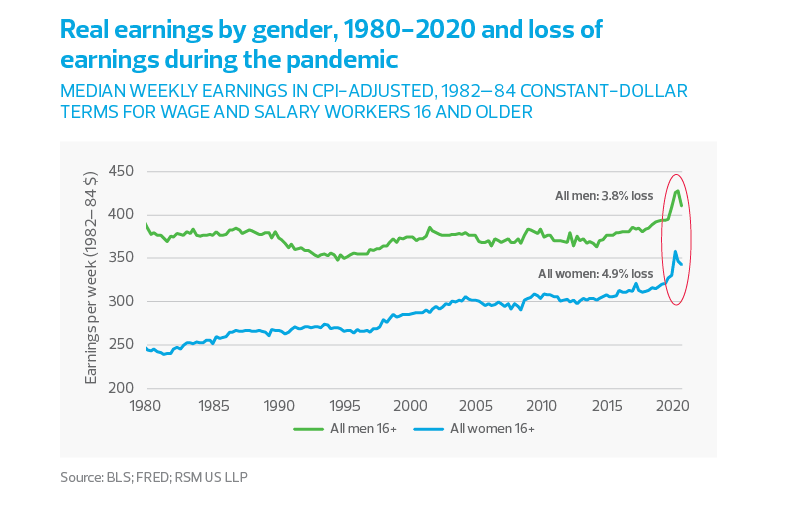

There are a host of reasons for the larger drop in women’s wages during the 2020 economic shutdown, including the retention of men with higher seniority than women, the resurgence of manufacturing, and the dormancy of service-sector industries.

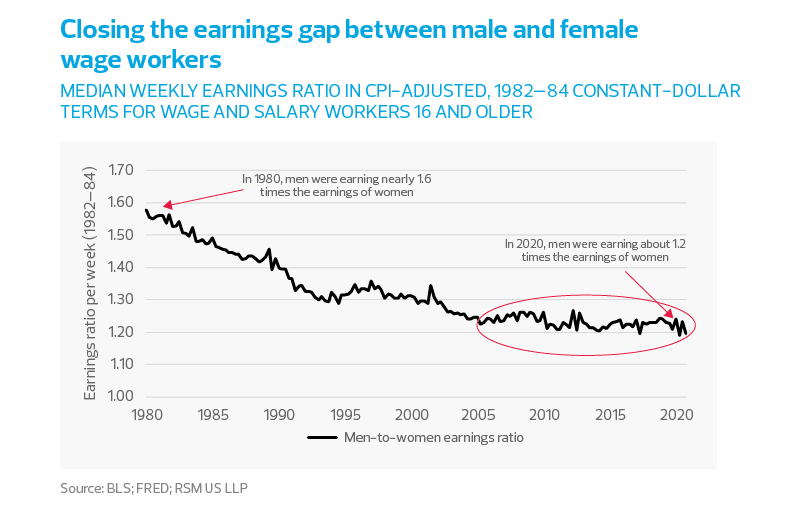

But there are reasons not to give up on the push for gender equality. Though the ratio of men’s-to-women’s wages seems to have hit a roadblock after improving from 1980 to 2005, this setback might be attributable more to family obligations that tend to fall more on women than men.

If there are lingering occupational preferences on the part of both employees and employers, that should become a thing of the past as the workplace adapts to the requirements of the new economy.

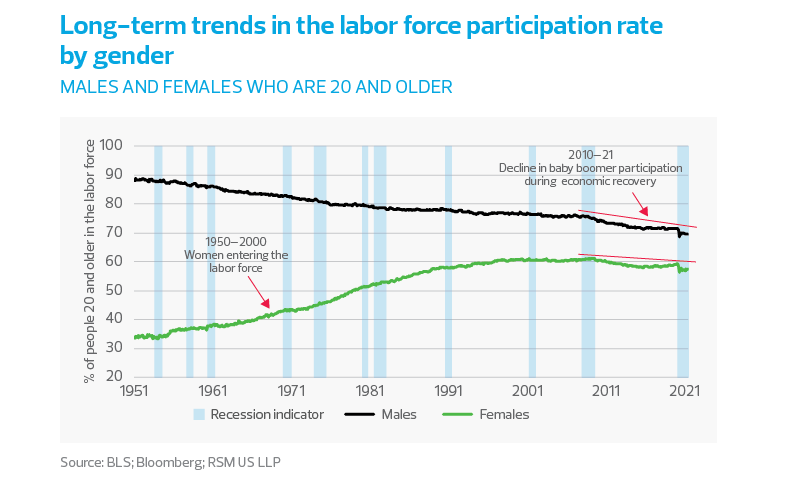

Labor force participation rate

Several trends were affecting the labor force participation rate among men and women before the pandemic.

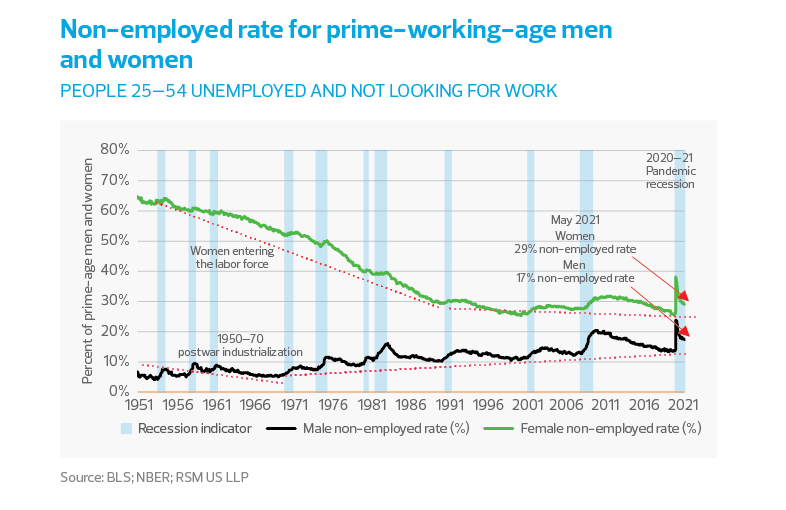

Although 90% of men—those 20 and above—were active workers or were actively seeking employment in 1950, that ratio had dropped to 75% by the onset of the Great Recession. Women’s role in the labor force was a mirror image, increasing from a participation rate of 31% in 1950 to a peak of 61% in 2008 as both employment opportunities and family roles were changing.

The Great Recession arguably prompted another shift. By 2010, baby boomers began to leave the labor force. By 2019, the participation rate for men had declined to 71%, while only 59% of women remained in the labor force.

By April 2020, the pandemic had reduced the number of men 20 and above in the labor force by 3.0 million (or 3.6%) relative to 12 months earlier, and a labor force participation rate of 65.6%. There were 2.6 million (or 3.5%) fewer women in the labor force, for a participation rate of 56.3%.

MIDDLE MARKET INSIGHT: As the hospitality sector opens up, we could expect women to rejoin the labor force at increased rates.

From September 2020 to February 2021, women were leaving the labor force at a faster rate than men. Reports suggested that more women were staying home to care for their children, which might have a lot to do with existing wage and salary disparities, as well as the reassertion of traditional family roles in the absence of affordable child care services.

As the hospitality sector opens up, we could expect women to rejoin the labor force at increased rates.