On June 25, 2021 the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) released draft tax ruling TR 2021/D4 Income tax: royalties – character of receipts in respect of software (the draft ruling). If finalized, the draft ruling will apply to transactions preceding and subsequent to the issuance of TR 2021/D4. The ATO also withdrew a previous ruling on computer software, TR 93/12.

The draft ruling describes the ATO’s views regarding the characterization of income from licensing and distributing computer software, and interprets the definition of royalty in section 6(1) of the ITAA 1936. The draft ruling acknowledges that the character of income from licensing and distributing software depends on the terms of the agreement between the parties, taking into account the facts and circumstances of the particular case. The draft ruling does not address how income should be characterized if it is not a royalty. However, it sets out certain guidelines to apply in conducting the analysis of whether a payment for software is a royalty or another class of payment. The characterization of a payment as a royalty under Australian domestic law is important for purposes of determining whether it will qualify for a reduction in the Australian rate of withholding under Article 12 of the U.S.-Australia Income Tax Treaty.

According to the draft ruling, a payment is a royalty under section 6(1) of the ITAA 1936 to the extent it is paid or credited as consideration for one or more of the following:

- The grant of a right to “do something in relation to software” that is the exclusive right of the owner of the copyright in the software, including payments for rights that permit a licensee to (i) reproduce, modify or adapt software, or (ii) sub-license the use of the software, whether by means of carry media, digital download or cloud-based technology.

- The supply of know-how in relation to software.

- The supply of assistance furnished as a means of enabling the software application.

A license to an end user for the “simple use” of software under an End User License Agreement (EULA) is not characterized as a royalty under the draft ruling. End user license agreements have historically been used in conjunction with software downloads. However, they may also be used in conjunction with cloud-based software applications in addition to an end user service agreement. Software code (or source code) is protected under the copyright laws of most countries. However, not all payments for rights that are protected under copyright laws are characterized as royalties for tax purposes. Many countries make a distinction between the grant of rights that are limited to rights to use the software (such as a EULA granted to an end user) for which payments are not royalties, from rights to adapt, modify or reproduce for purposes of resale, which typically are royalties. The ATO ruling is generally in line with this approach.

Distribution arrangements

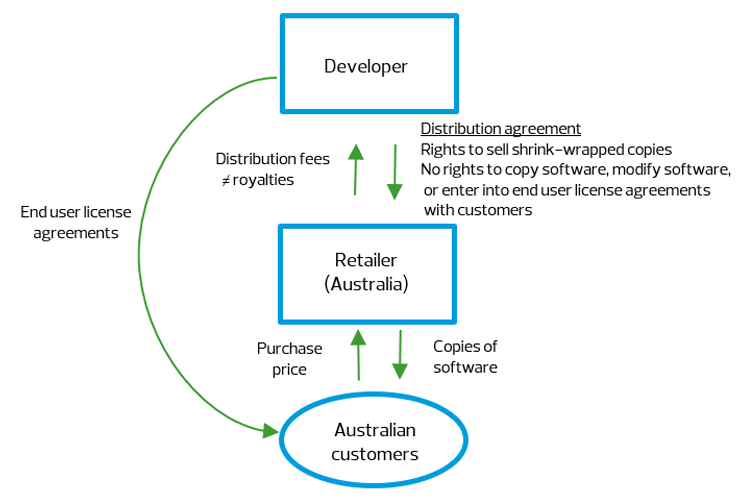

One of the more significant aspects of the draft ruling is that it provides some parameters around the types of distribution arrangements that may create a royalty for Australian tax purposes, rather than a buy-sell arrangement, often with significantly different tax results. A distribution relationship that does not give rise to royalty income under the draft ruling could be viewed as a buy-sell relationship, or the distributor could be treated as a service provider/agent of the software developer, in which case the sales revenue may be treated as having been earned directly by the software developer and the distributor may earn a service fee for its distribution services.

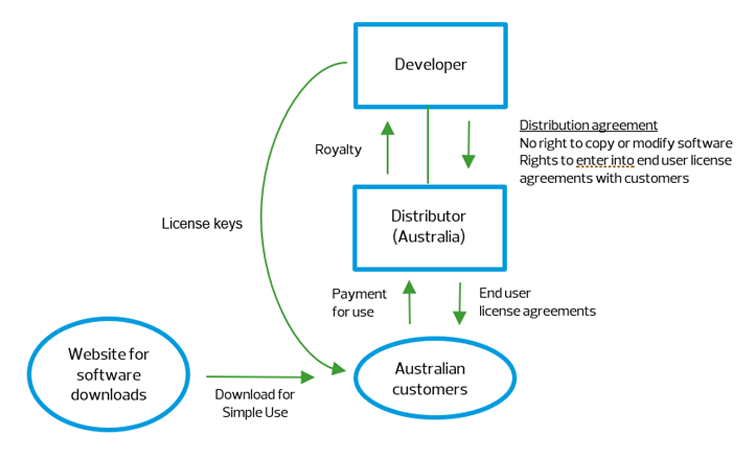

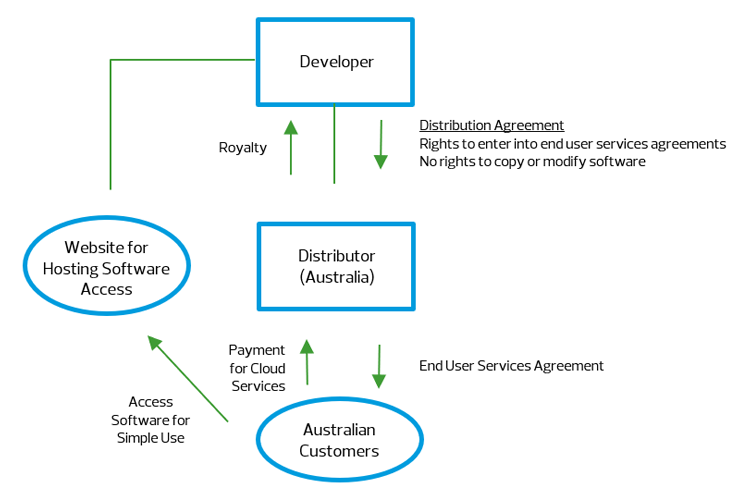

Payments a distributor makes to a copyright holder for rights to reproduce software for purposes of resale are characterized as royalties under the draft ruling. A distributor that does not obtain rights to reproduce the software for purposes of resale may still be treated as having obtained rights compensable to the copyright holder as a royalty if the distributor enters into EULAs with end users. Examples 4 and 5 (see below) in the draft ruling indicate that this would be the case even if the software was downloaded or accessed from a website maintained by the copyright owner or a third-party. The rationale provided in the ruling for placing significance on the EULAs is that when the distributor enters into the EULAs the distributor is standing in the shoes of the copyright owner and exploiting the copyrights to derive income. Interestingly, the draft ruling does not analyze the level of operating risks assumed by the distributor in conjunction with the distribution relationship. It would appear, based on the draft ruling, that a limited risk distributor with a guaranteed profit margin and cost reimbursement agreement with the software developer could still give rise to royalty income if the distributor enters into the EULA with end users.

Example 4 (software distribution agreement conferring rights to enter into EULA): A software development company enters into a distribution agreement with its Australian subsidiary to distribute copies of the software to customers in Australia. The Australian subsidiary enters into EULAs. The subsidiary is not granted rights to reproduce or modify the software. When a customer places an order with the subsidiary, the subsidiary notifies the parent to issue a license key for the customer to unlock the software. Customers download the software from a website that is not maintained or controlled by the Australian subsidiary. The ruling concludes that the payments from the Australian subsidiary to the parent are royalties.