Even amid banking turmoil, the Fed raised its policy rate by 25 basis points in March.

Key takeaways

The rate increase demonstrated the Fed’s commitment to taming inflation.

The probability of the Fed avoiding a hard landing would appear quite low.

Joseph Heller's novel “Catch-22” delved into the impossible conditions imposed on people caught in situations from which there is no escape because of mutually conflicting or dependent conditions. That catch-22 is an apt description of where the Federal Reserve finds itself as it lifted its policy rate by 25 basis points at its most recent meeting amid a quickly evolving global banking crisis.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell is trying to navigate a “trilemma” that demands the central bank reestablish price stability, minimize unemployment and restore financial stability.

With its quarter-point increase, the Fed signaled it intends to strike that delicate balance by hiking rates and providing forward guidance that implies a far less restrictive stance than the market had priced in before the banking turmoil.

The key phrase in the Federal Open Market Committee’s statement communicating that policy challenge is: "The Committee anticipates that some additional policy firming may be appropriate in order to attain a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive to return inflation to 2% over time."

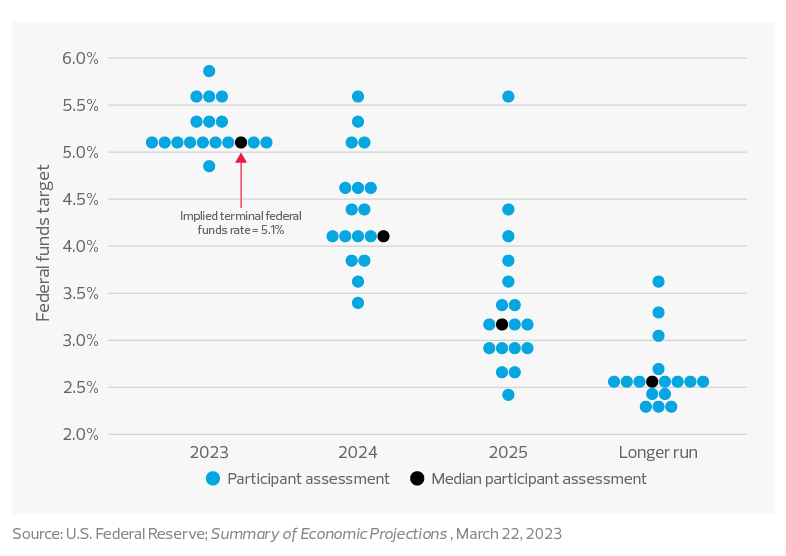

The Fed forecasts a median policy rate of 5.1% for 2023, implying only one more rate hike this year.

The Fed now forecasts a median policy rate of 5.1% for 2023, implying only one more rate hike this year, as well as a median 2.5% long-run rate with a median rate of 5.1% this year, a 4.3% rate next year and 3.1% in 2025.

The Fed has now imposed a soft rate-hike bias into its forward guidance, which in our estimation, signals that we are at or near the peak policy rate.

Given our modeling of the recent financial shock that implies a de facto additional 50 basis points of tightening on top of the 25 the Fed just added, the Fed is well into restrictive territory.

The probability of the Fed sticking the landing on this without causing a recession, increasing unemployment and preventing further consolidation in the domestic banking sector appears to be quite low.

As such, a rate hike in June would be roughly the same as an extended pause at this point. The evolution of the data and the extent to which financial conditions ease or tighten, as well as the status of the type of deposit guarantee by the federal government, will most likely drive that decision.

The Fed, in statements and comments following its most recent meeting, tried to signal to investors, policymakers and firm managers that it can walk and chew gum at the same time.

That is, it has the tools to simultaneously achieve price stability and financial stability.

But that will almost certainly result in higher unemployment under conditions now imposed by the liquidity squeeze that has impaired community and regional banks.

Pervasive uncertainty

While the Fed has signaled that it intends to continue its efforts to restore price stability, financial conditions have tightened to the point where our modeling of the recent turmoil suggests that an equivalent of 50 basis points of policy tightening has occurred. That tightening implies a Fed proxy rate of 5.25% to 5.5%, above the federal funds target range of 4.75% to 5% that it has now committed to maintaining

The median rate of 5.1% implied by the Fed’s dot-plot forecast of interest rates through the end of the year suggests that the Fed intends to achieve price stability. Yet the Fed is also cognizant of the risks to the outlook caused by financial instability.

As long as the recent instability does not deteriorate and the liquidity provided by the Fed and Treasury proves sufficient, the Fed can continue to emphasize the price stability portion of its mandate.

Another round of financial instability would almost certainly require, at the very least, a pause in the Fed’s rate hike campaign.

But another round of instability in the domestic banking ecosystem or a further roiling of systemically important financial institutions would almost certainly require, at the very least, a pause in the Fed’s rate hike campaign and a focus on its considerable toolbox to obtain financial stability.

Our research suggests that should the current banking turmoil intensify and engulf a systemically important financial institution, the deterioration in financial conditions would be equivalent to a 150 basis-point increase in policy tightening and push the proxy federal funds rate well above 6%.

That would create the conditions for a near-term recession and an abrupt shift in policy toward accommodation before the end of the year.

For now, we expect the status quo to hold and are leaning toward one more 25 basis-point rate hike. That would bring the official policy rate to 5% to 5.25% and would be in line with our estimation of the current proxy rate, which is quite restrictive.

Expecting rapid change

The risk posed to the economy by the banking turmoil injects a larger degree of uncertainty around the Fed’s Summary of Economic Projections and rate forecast.

In our estimation, the Fed’s growth, employment and inflation forecast is not well aligned with the recent shock.

Given the role played by small and medium-sized banks in residential mortgages, commercial real estate and auto lending, that growth will slow and will most likely tip into recession later this year on the back of tighter lending and rate hikes.

One should anticipate on-the-run updates of the forecast by Federal Reserve members until the Fed issues its next SEP in June.

The recent SEP acknowledged the obvious, which was that the economy is slowing and inflation is higher than the forecast put forward in December.

FOMC participants’ assessment of the appropriate federal funds target rate

The Fed now expects a growth rate of 0.4% this year, in contrast with its previous estimate of 0.5%. The unemployment forecast of 4.6% at the end of the year remains unchanged, as did the Fed’s estimate of headline inflation of 2.5%. The forecast of core inflation ticked up to 2.6% from 2.5% previously.

Growth next year is now expected to be between 1% and 1.5%, unemployment between 4.3% and 4.9%, and core inflation between 2.3% and 2.7%.

Press conference: Threading the needle

Powell, at the outset of his recent press conference, wisely emphasized that deposits are safe and that the Fed has an impressive array of tools to restore financial stability.

Liquidity remains ample and the Fed stands ready to act to maintain the functioning of the financial system.

The prepared statement in the press conference, along with the SEP and dot-plot forecast, reflects a crucial compromise to solve the challenging policy dilemma that lies ahead.

Powell also went out of his way to acknowledge that the turmoil in banking has caused a general tightening of financial conditions that may affect policy. He linked that to the changes in the forecast and the policy statement that indicated some additional policy firming may be needed but was no longer guaranteed.

Pressed on the Fed’s regulatory oversight of the banks and accountability issues, Powell acknowledged a need to improve supervision and regulation but mostly demurred from directly addressing the issue. Oversight will be an ongoing thorn in the side of the central bank.

Asked about the risks to the economy posed by commercial real estate, Powell said that it is not at the level of risks around banks and the economy.

While that is accurate, one gets the sense that the Fed policy path this year and next will be shaped in part by the rollover risk embedded inside the commercial real estate community and the fact that small and medium-sized banks hold 67% of the outstanding commercial real estate loans.

The takeaway

The path of monetary policy is uncharacteristically uncertain. It appears that we are at or will soon approach the policy peak for this cycle, as policy has moved well into restrictive terrain.

The economic forecast is not well aligned with the current risks to the economic outlook caused by the banking turmoil and will need to be revised down at the next FOMC meeting.

Until the fiscal authority can resolve whether the implicit guarantee of bank deposits is sufficient or a more explicit guarantee of those deposits is needed to prevent a further run on banks, the Fed is essentially Plan B.

Serving in that role will require an unusual degree of flexibility on the part of the central bank with respect to both its price stability through the policy rate and the tools it can deploy to restore financial stability.