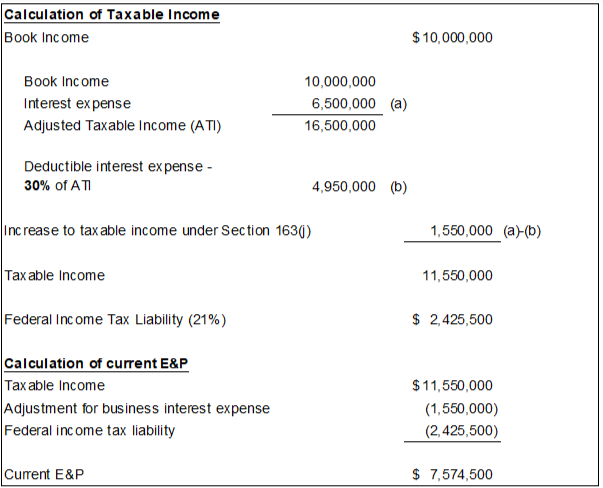

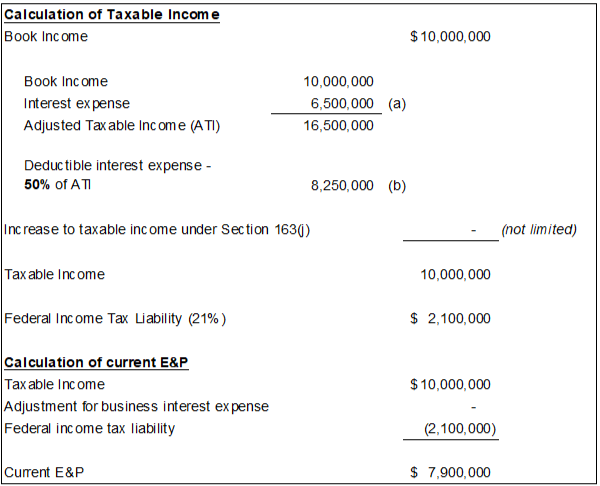

Based on the hypothetical E&P computation above, if the changes under the CARES Act were to be accounted for retroactively in determining E&P, the corporation would have underreported the 2019 dividend income to its shareholders by $325,500 ($7,900,000 – $7,574,500). This would cause Form 1099-DIV reporting issues as well as potentially Form 1040 reporting issues if individual shareholder tax returns have already been filed.

Similar to the changes to section 163(j), other retroactive changes under the CARES Act can lead to similar outcomes in terms of E&P. For example, the CARES Act retroactively treats qualified improvement property (QIP) as 15-year property, eligible for bonus depreciation, for property placed in service starting in 2018. Furthermore, the Act changes the QIP alternative depreciation system (ADS) recovery period to 20 years. Given the impacts these changes can have on E&P, a determination must be made as to which year the adjustment to a company’s E&P should be reflected in.

Neither section 312 nor the treasury regulations thereunder explicitly address the proper treatment of retroactive changes in the tax law. Regs. section 1.312-6(a) instructs corporations to compute E&P using “the method of accounting properly employed in computing taxable income.” A reasonable interpretation would suggest the proper method of accounting would be in accordance with the tax law enacted as of that date, but when that law is retroactively changed, when should the E&P adjustment be properly recorded? The most reasonable approach may be found in case law.

In Sweets Company of America v. Commissioner, 8 T.C. 1104 (1947), the Sweets Company of America (Sweets Company) filed its excess profits tax liability returns in 1942 and 1943 on the basis of invested capital. One such element of invested capital is accumulated E&P as of the beginning of the year. In 1942, Congress retroactively amended the undistributed profits surtax provisions which entitled Sweets Company to a refund of its previously assessed surtax for the 1936 and 1937 tax years.

The question at issue in the case was the timing of the inclusion of the refunds in accumulated E&P and, thereby inclusion in invested capital. Sweets Company argued that that accumulated E&P from 1936 and 1937 should be restored on account of the refunds since Congress amended the law retroactively. The IRS, on the other hand, contended that amounts cannot be restored to accumulated E&P prior to the amendment of the law in October 1942.

The Tax Court ultimately ruled in favor of the IRS that the refunds in question were not a part of Sweets Company’s accumulated E&P until the enactment of the 1942 law. In its opinion, the Court emphasized the fact that the “taxes which petitioner paid for 1936 and 1937 were properly levied against it under the then existing law.” The opinion went on to say “Here, when the petitioner paid its tax for 1936 and 1937, there was no overpayment; and it had no claim whatever to recover the tax until Congress gave it that right in 1942.”

Applying the same rationale that the Tax Court applied in Sweets to the enactment of the CARES Act and the related implications on a corporation’s E&P, the initial reduction to E&P for federal income tax, as computed prior to the enactment of the CARES Act, was the proper adjustment “under the then existing law.” Furthermore, a corporation would have no reason to believe the computation of its federal income tax liability as computed under the then existing law was over or understated. The application of Sweets, while taking into account the previously mentioned considerations, validates the position that where a change in tax liability is a result of statutory amendments enacted after the close of the taxable year to which the change applies, such change in liability should be included in the E&P for the year in which the statutory amendment relates. Consequently, a reasonable argument exists to make adjustments to a corporation’s E&P that resulted from the effects of the CARES Act (e.g. change in tax liability, QIP change in ADS recovery period to 20 years, etc.) in 2020, the year of its enactment.

While the CARES Act provides for much needed relief to companies experiencing economic hardship, it also adds much complexity to federal tax compliance. Corporations should consider all of the potential impacts the CARES Act may have on their overall tax position. Given the complexity of the tax provisions of the CARES Act, corporate taxpayers should consult with their tax advisors to ensure compliance in all areas.

For a more detailed analysis of the CARES Act and other COVID-19 materials affecting businesses, please visit RSM’s Coronavirus Resource Center and Coronavirus Tax Relief Resource Center.