UPMIFA overhauled the rules for managing and spending from donor-restricted endowments

Key takeaways

Accounting standards also updated for net asset classification and presentation of endowment funds

While UPMIFA is not new, there is still confusion around compliance

Understanding common missteps helps organizations take the right direction

This article was originally published on Oct. 30, 2020 and was updated in April 2023.

The Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act (UPMIFA) was enacted by 49 states and the District of Columbia more than a decade ago (Pennsylvania is the lone holdout, but has its own law in this area). UPMIFA completely overhauled the rules for managing donor-restricted endowments and the accounting standards were also updated in response. However, many organizations have still not realized that the rules have changed; they have continued to follow the principles of the old rules and may not even realize that they are out of compliance. The following are five common myths/misunderstandings when it comes to endowment funds:

No. 1: We must protect only the fund corpus

The predecessor to UPMIFA was UMIFA (Uniform Management of Institutional Funds Act). UMIFA placed a requirement/focus on the original gift amount, commonly referred to as the “corpus”. If the invested funds fell below the corpus, charities/institutions (organizations) were prohibited from further spending until the corpus recovered.

Under UPMIFA, this concept is now extinct to a large degree. UPMIFA now focuses on preservation of purchasing power of the endowment fund over time. Under the concept of inflation, the total fund value needs to increase over time in order to hold its value. For example, $1 in 1970 was worth $6.82 in 2020. If a gift of $100,000 was made to an organization in 1970, the fund would need to have a total value of $682,000 in 2020 to maintain that purchasing power if the UPMIFA rules had been in place since 1970. If an organization only focuses on the corpus, and did not allow for growth, this fund would be severely watered down in its funding potential through 2020.

UPMIFA calls for prudent investing along with prudent spending that allows for fund preservation over time. This is accomplished by listening to investment advisors as to the assumed long-term rates of return based on the investing strategy (typically focused on growth), and then choosing a spending policy that allows for growth. For example, if your investment advisor says your endowment investment portfolio is projected to have a long-term rate of return of 6.5%, and inflation rates are 1.3%, the organization should choose a spending rate of 5.2% or below as the best prudent decision to maintain purchasing power. Since short-term market rates can fluctuate wildly from year to year, organizations should resist the temptation to greatly increase spending in a year where the market had double-digit growth.

UPMIFA even allows organizations to spend from “underwater” endowments if they feel it is prudent to do so. Underwater funds are where the fund value drops below the corpus. Again, the theory goes to long-term averaging, with the assumption that over the long term, rates will normalize back to the projected long-term estimated return. Admittedly, many organizations feel nervous about spending from underwater funds and may decide the prudent move is to suspend spending until the fund has recovered. However, it is important to recognize the choices that UPMIFA now provides over UMIFA.

No. 2: The donor gift agreement allows us to spend all earnings on a current basis

UPMIFA does take a back seat to donor intentions. Where the donor is explicit in their instructions, organizations can follow those instructions without fear even if they go against the principles of UPMIFA. The reality of the situation is that donors are rarely explicit enough in their instructions to override the UPMIFA guidelines for prudent investing, prudent spending and maintenance of purchasing power.

The following is a typical clause in a donor endowment agreement:

This donation of $100,000 is to form the Jane Jones Memorial Endowment Fund. The fund must be maintained as an endowment fund in perpetuity and earnings from the fund are restricted to the organization’s adult tutoring program.

Many organizations will look at the clause “earnings from the fund” and conclude that any and all earnings can be spent on a current basis. However, this wording is not explicit enough. UPMIFA acts on behalf of the donor and assumes a donor would want his or her fund’s purchasing power maintained over time so that the permanent fund stays just that. The spending from the fund will still be restricted to the adult tutoring program, but will just be at an annual level that adheres to a prudent spending policy of the organization. In order to spend at a much greater rate, the wording from the donor would need to be along these lines:

We are donating $100,000 to form the Jane Jones Memorial Endowment Fund. The fund must be maintained as an endowment fund in perpetuity in the amount of $100,000. Any earnings in the fund (above $100,000) can be spent on a current basis for the restricted purpose of funding the organization’s adult tutoring program.

If the organization is looking to maximize its flexibility for managing the endowment funds and wants to avoid the requirements of UPMIFA, it should work with its donors as its as the endowment agreement is drafted to ensure the terms/instructions are very explicit.

No. 3: Earnings from endowment funds without explicit restrictions on use should be recorded to net assets without donor restrictions

Donor-restricted endowment funds come in many different flavors. While many funds specify a restricted purpose for the fund in terms of how the spending must be used, there are other endowments called unrestricted endowments. This term should not be confused with board-designated or quasi endowments, where an organization takes its own surplus of liquid funds and creates a designated fund to act as endowment funds. Rather, unrestricted endowment funds are donor-restricted perpetual funds, but the earnings (from the spending policy) can be used for general activities of the organization. Under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), the entire endowment fund value (for donor-restricted endowment funds) must be recorded to net assets with donor restrictions even if there are no purpose restrictions on the use of the funds. Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) Topic 958 (not-for-profit entities) requires the entire fund value to be recorded within restricted net assets since the spending is subject to limitations under UPMIFA (i.e., considered time restricted). Once an amount is appropriated for use in a given year using a prudent spending policy, the spending amount from an “Unrestricted Endowment” would then be deemed to be unrestricted and available for use by the organization.

Prior to UPMIFA, many organizations recorded the appreciation of unrestricted endowments to the unrestricted category of net assets. When UPMIFA became effective in the applicable state of the organization, a reclassification should have occurred to move the appreciation into restricted net assets. However, we have found in practice that many organizations were not fully informed of the changes under GAAP, and have assisted them with their correction of this practice. Thus, a total fund value concept should be used for each endowment fund. All of the activity occurs within restricted net assets from the beginning fund value, plus new contributions made during the year for the endowment fund, plus all investment income (less investment losses). Only when the spending policy for the year is activated does that amount leave the restricted fund balance.

No. 4: Tracking investment earnings is more of an art than a science

We have seen some very creative methods of allocating investment return to endowment funds over the years. Related to the third point above, we have seen unrestricted endowment funds not receiving their fair share of return under the incorrect notion that those earnings are not restricted. We have also seen where the return is artificially limited based on some notion of a cap. In many cases, organizations are just over-thinking what should be a straightforward concept.

The allocation of investment income is dependent on how the funds are invested. In a very simple situation, an organization has just one permanent endowment fund, and a single investment account is used to hold the investment of that one fund (i.e., nothing is comingled). In this case, the actual investment results of that fund are applied to the endowment fund. Also, to make tracking easier, the organization should physically pull the spending amount from the account and timely remit any new contributions to the fund into the account. If done correctly, the balance of the investment account at year-end should also be the restricted amount of the endowment fund.

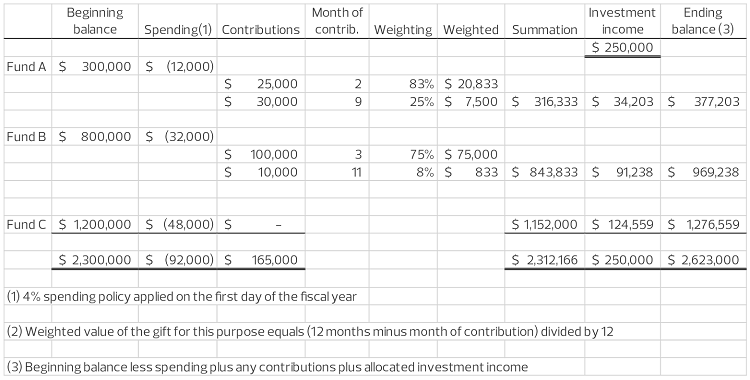

Fortunately for many organizations, they have multiple endowment funds, as well as quasi endowment funds, and other investments not tied to any particular fund. This can be unfortunate for the accounting department that has to keep track of the many funds organized in a comingled environment. There are investment advisors and other vendors who, as a service, can unitize the aggregate holdings back to specific funds to aid in the tracking. This is common for very large situations in terms of the value of invested funds and the number of funds to be tracked. However, many organizations have to go it alone and need a good spreadsheet to aid in the process. The ultimate goal is to allocate the return (or loss) based on average fund value. Thus, a fund that is twice the size of another fund should have twice as much return as the smaller fund, etc. The table below illustrates this concept:

Ultimately, the funds should get their fair share of the total return of the investments using a reasonable method of allocation.

No. 5: The board can create a donor-restricted endowment fund

For purposes of classification and applicability of UPMIFA, only a donor can create a donor-restricted endowment through its gift agreement/instrument or will. However, if the donor does not establish an endowment fund (or any type of restricted gift for that matter), the board has no power to step in to re-characterize the gift to make it into one.

The following is a typical example of what we have seen when a board has gone too far:

In 1991, an organization received a bequest in the amount of $1 million from the estate of Zach Zimmerman. Mr. Zimmerman’s will made provisions for the gift but no further instructions or restrictions were stated. Upon receipt of the gift, the board made the following resolution:

We are honored that Zach Zimmerman felt so strongly about the mission of the organization that he remembered us in his will for a bequest of $1 million. Zach served on this board for many years and many board members remember how passionate he was for the food pantry program (FPP) of the organization and that we know he would want his gift to provide for a steady stream of support for that program. Thus, we have passed this resolution to establish the Zach Zimmerman Memorial Endowment Fund that will become a permanent endowment fund of the organization in support of the FPP.

There is nothing to prevent the organization from establishing a board-designated endowment fund with the proceeds of an unrestricted bequest, but it would still be considered an unrestricted fund of the organization. A simple vote of the board would be able to undesignate the fund as quickly as it was established. The mistake here is that the accounting function took the resolution literally and recorded the bequest as a restricted net asset, and tracked it as a permanent endowment from that point forward. In 2011, the organization hired a new chief financial officer. One of her early projects was to examine all of the endowment funds of the organization and to make sure the files were complete as to the original gift document and how UPMIFA should be applied (e.g., are explicit instructions present that override UPMIFA or not, etc.). Through this process, the CFO came upon the Zimmerman Fund, and quickly realized that this was not a restricted fund as there were no restrictions in the decedent’s will. She notified the auditors quickly thereafter. The fund at this point had grown to be $3.2 million, which is an amount that is material to the financial statements.

GAAP states that errors within the net assets classifications are financial statement errors, even if the total amounts are correct. In this case, restricted net assets were overstated by $3.2 million, and unrestricted net assets were understated by the same amount. Total net assets are not affected. Material misclassifications such as the one in this example would have to be corrected via a prior period adjustment (e.g., current year reclass would not be a proper resolution).

No one likes a restatement. It is important for organizations to properly classify contributions based solely on the stated restrictions placed by the donor or the lack thereof. Internal designations are also important to track and properly disclose in the financial statements but retain their appropriate restricted or unrestricted net asset classification.

Summary

As with many aspects of nonprofit accounting under GAAP, endowment accounting can be rather complex. Organizations are subject to state law when it comes to UPMIFA (keeping in mind that Pennsylvania has its own law), as well as prescribed accounting treatments under ASC 958. If your organization has donor-restricted endowment funds, the responsibility falls to management to comply with the law and conform to GAAP. Management should ensure staff members are properly trained in these matters and that internal controls are designed and implemented to mitigate risks such as the five areas highlighted above, and that the objectives are met. As with any matter of law, please consult with legal counsel if the organization has questions on the application of UPMIFA, as needed.

RSM contributors

-

Tom SneeringerPartner

Tom SneeringerPartner