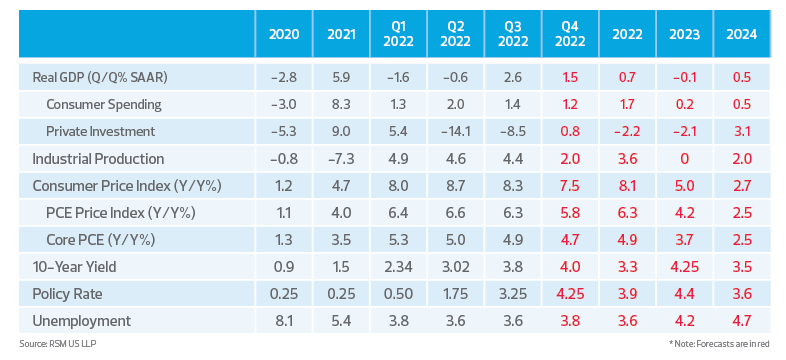

The combined dynamics on growth, inflation and employment will lead the Federal Reserve to consider redefining its inflation target to 3% and to pivot its focus away from price stability and toward employment.

We do not expect rate cuts to begin until early 2024.

Our alternative to this baseline forecast is that inflation abates early next year and, combined with a strong and steady labor market, bolsters confidence in a way that narrowly avoids a recession.

That alternative hinges on the chance that the central bank keeps rates steady throughout the year as economic growth slows below 1%.

Risks to the outlook

The primary risk to the economic outlook is elevated inflation sapping household demand as incomes decline. Other risks include the rising cost of issuing public and private debt, and a potential standoff in Congress over lifting the debt ceiling.

In some respects, the debt ceiling is the biggest wild card. The U.S. fixed income market remains the linchpin of the global economy. Default is not an option, and another debt ceiling debacle along the lines of the one in 2011 would damage corporate and consumer confidence.

In such a standoff, asset prices would decline and American consumers would pull back on spending, creating further downward pressure on the economy at a vulnerable time.

This does not have to occur and is a choice of the political authority. The risks, though, are considerable and would affect the Fed’s policies.

The second major risk to the economic outlook is tied to the Russia-Ukraine war. The United States and its allies are trying to place an effective price cap on Russian oil exports. If Russia retaliates by terminating all oil exports to the West and Japan, the inflation and policy outlooks will change rapidly and the prospect of a deeper recession will be at hand.

Policy considerations

The question, then, is what the Fed will do as a recession approaches and how Congress can bolster aggregate demand given elevated inflation and a renewed resistance to fiscal stimulus.

First, we expect the central bank to hike its policy rate by 50 basis points at its December policy meeting, then by 25 basis points at its January and March meetings. Those increases would bring the policy rate to between 5% and 5.25% by the end of the first quarter.

Then we expect the Federal Reserve to engage in a lengthy pause to ascertain the impact of its rate hikes over the previous year. Recent policy has clearly resulted in fewer housing starts and has led to price depreciation in some areas. In addition, rising interest rates will most likely further sap demand for automobiles.

Second, the policy outlook for the fiscal authority will be constrained by higher inflation and political gridlock.

Republicans, having regained control of the House of Representatives, will almost certainly call for the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act to be made permanent and push to expand the production of oil and other fossil fuels. Democrats, in control of the Senate and the White House, will have other ideas, including a renewal of the expanded child tax credit that proved popular and effective during the pandemic.

We think there will be some agreement around policy measures that could include:

- Extending and enhancing unemployment insurance

- Extending and enhancing food stamps and other aid to needy families

- Pulling forward supply side increases in infrastructure spending from future years and accelerating the permit process for energy projects

- Allowing full expensing of productivity-enhancing capital expenditures

- Increasing tax credits and federal spending on research and development

Finally, given the broad structural changes in the global goods market and the decoupling of the American economy from China, higher inflation and higher interest rates are likely to continue.

That implies narrower fiscal space and a possible return to fiscal austerity to bring down inflation. It also indicates the chance of a deeper recession than our forecast calls for.

Inflation: Easing but still elevated

Negative base-year effects linked to higher food and fuel costs will drive down top-line inflation through the middle of next year, setting up a fierce policy debate over how long the Federal Reserve should hold its policy rate at or above 5%.

We anticipate that by the end of the year, the consumer price index will reside at or below 5% and the core personal consumption expenditures index will stand at or near 3%.

Both are well above the Fed’s 2% inflation target, a figure that will require careful consideration of policymakers at both the monetary and fiscal authorities.

Our forecast anticipates further normalization of supply chains, declines in transportation costs, a peak in shelter costs and slower wage growth.

All those dynamics will contribute to a substantial easing in overall inflation next year, helped by the negative base-year effects in food and energy.

In particular, the goods constraint that hurt manufacturing and technology sales this year will be

lifted as the production of microchips returns to pre-pandemic levels. This, in turn, will set the stage for what we expect to be a modest recovery in 2024.

In a recent research paper, we made the case that core inflation would not substantially ease until after the cost of shelter and rents peaked, which we do not anticipate until the third quarter of next year.

From our vantage point, shelter costs need to be tamed before the easing of monetary policy can be considered.

Housing inflation remains high, approaching 9%. In our view, it is premature to end efforts to restore price stability. Any notion of a pause or pivot in that pursuit would result in a costly series of stops and starts in monetary policy that would only prolong elevated inflation.

But there is relief in sight when it comes to housing. One million apartment units are either permitted or under construction, the most in six decades. Those new units will provide relief on overall housing costs later next year and into 2024.

Because of all these factors, we do not see the Fed seriously considering rate cuts until late next year or, more likely, early 2024.

Financial conditions: Tightening

Current financial conditions stand between 1.5 and two standard deviations below neutral because of rising interest rates, volatility in asset prices and a 17% decline in the S&P 500 as of the end of November.

Because tighter financial conditions are one objective of the Fed’s price stability campaign, we do not anticipate any sustained improvement in asset prices until the central bank signals it intends to pause rate hikes.

In addition, we will not see a real recovery in asset and housing prices until the central bank begins hinting at possible rate decreases later next year.

For now, risk appetite will remain subdued, and a mild negative wealth effect that will disproportionally hit upper-end consumers is in the cards.

The interest rate outlook remains dour. We expect the yield on the 10-year government security to finish this year at or near 4% and to average 4.25% next year.

If the policy rate sits between 5% and 5.25% for much of the year, as we expect, an inverted yield curve will likely prevail, which explains the general malaise that has crept into fixed-income markets.

Employment: Solid but slowing

Solid, albeit slowing, employment gains will most likely characterize hiring conditions during the first part of next year, followed by outright declines in the second half.

The forward-looking employment component of our RSM US Middle Market Business Index indicates that just over half of the survey’s respondents expect to increase hiring over the next six months.

Given the significant demographic changes and the slowing in labor market growth to below 0.5%, the economy needs to generate only 65,000 workers per month to keep the unemployment rate stable.

This is a major reason why we do not anticipate a large increase in unemployment above the 4.4% implied by the Congressional Budget Office, though we expect the rate to hit 4.6% by the end of the year.

Household spending: Exhaustion

Normally, a year-ahead forecast would lead with household spending, which accounts for roughly 70% of gross domestic product. But as households begin to access more credit and draw down their savings, especially among lower-income households, the recent run of inflation will begin to have an impact on spending—which is why we expect a modest 0.5% increase in consumption during the year ahead.

Though roughly $1.9 trillion in excess savings is still in consumer pocketbooks, most of it is in the upper two income quintiles. For these consumers, the combined decline in housing and equity prices should have a modest negative wealth effect.

Manufacturing: Pent-up demand

Pent-up demand for autos and a likely increase in military spending will put a floor underneath the manufacturing sector. We expect a modest 1% year-over-year rise in manufacturing output next year.

While that floor will partially offset a difficult transition to a higher-cost environment, it will not completely counter the shock of higher interest rates and rollover risk with respect to debt financing.

In addition, the delayed impact of U.S. dollar appreciation will dampen exports because of higher real costs and because of the recession in the United Kingdom and European Union, and, potentially, Canada and Mexico.

In each recession during the postwar era, the manufacturing sector has used that downturn to become more efficient. We do not anticipate the coming slowdown to be any different.

A higher cost of financing will almost surely lead to consolidation in manufacturing amid a permanent rise in costs. Adding to this consolidation is the return of industrial policy in areas like semiconductor manufacturing. Expect firms with economies of scale to make their own strategic acquisitions and take advantage of this shift in economic policy.

Housing: Considerable collateral damage

Pandemic-induced distortions within the housing complex and the bleeding of inflation into the cost of shelter will be the defining narratives in the housing sector next year.

We expect just under a 10% correction in housing prices, with the risk of a large downturn in metropolitan areas that had a population influx during the pandemic. Metros like Austin-Round Rock, Texas; Boise, Idaho; and Salt Lake City-Provo, Utah, may have large downturns as rising financing costs and affordability issues drive a correction.

While that will provide some relief on longer-term supply issues, it will not prove decisive. Our own research indicates that the United States is short approximately 3.5 million housing units and needs to build around 1.7 million units a year to meet overall demand. The housing complex would do well to return to building 1.5 million units at an annualized pace by the end of the year.